The Accidental Invention of the Slinky

The idea for the timeless toy sprung to mind when Naval engineer Richard James dropped some coiled wires

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/b7/5ab7576a-7582-42ee-b6de-02f00df08e7b/slinky.jpg)

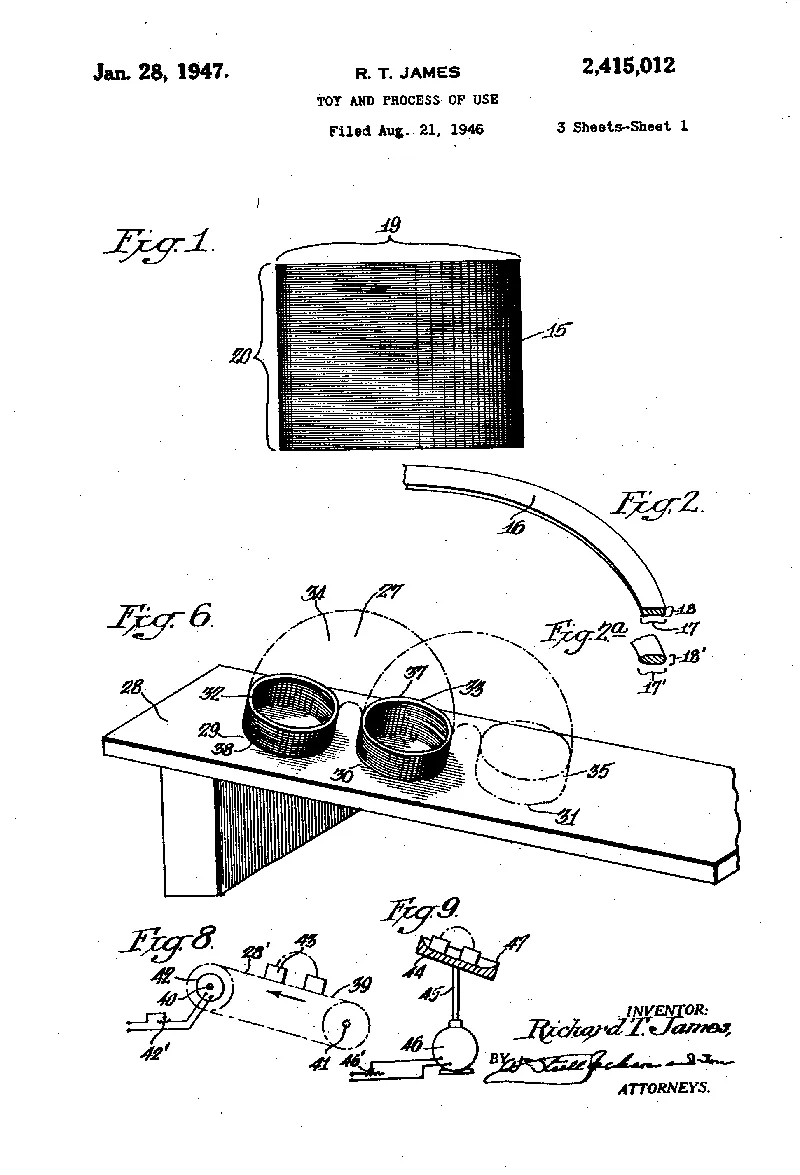

As its jingle once cheered: “A spring, a spring, a marvelous thing! Everyone knows it’s Slinky.” The coiled toy certainly is a marvelous, if simplistic, thing. In 1943, mechanical engineer Richard James was designing a device that the Navy could use to secure equipment and shipments on ships while they rocked at sea. As the story goes, he dropped the coiled wires he was tinkering with on the ground and watched them tumble end-over-end across the floor.

After dropping the coil, he could have gotten up, frustrated, and chased after it without a second thought. But he—as inventors often do—had a second thought: perhaps this would make a good toy. A lot of inventors talk about keeping an open mind and maintaining playful habits, explains Monica Smith, the head of exhibitions at Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation.

“The Slinky was something that he saw happen and he thought it was cool. It wasn’t an obvious idea for a toy,” she says. “It wasn’t something he was setting out for—it’s more serendipitous than that. He kept an open mind and found a different use for it.”

As Jonathon Schifman reported for Popular Mechanics, Richard James went home and told his wife, Betty James, about his idea. In 1944, she scoured the dictionary for a fitting name, landing on “slinky,” which means “sleek and sinuous in movement or outline.” Together, with a $500 loan, they co-founded James Industries in 1945, the year the Slinky hit store shelves.

At first, folks didn’t know what to make of it. How could a bundle of wire be a toy? The Jameses managed to convince a Gimbel’s department store in Philadelphia to let them do a demonstration during the Christmas shopping season in 1945. There were 400 Slinkys stocked that day, and they were gone in less than two hours—selling for $1 a pop, or about $14 in today’s value.

This Friday, on National Slinky Day, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission will be installing a historical marker to commemorate the invention of the toy in Clifton Heights, the Philadelphia suburb where it was first manufactured.

Seventy-two years ago, Richard James received a patent for the Slinky, describing “a helical spring toy which will walk on an amusement platform such as an inclined plane or set of steps from a starting point to successive lower landing points without application of external force beyond the starting force and the action of gravity.” He had worked out the ideal dimensions for the spring, 80-feet of wire into a two-inch spiral. (You can find an exact mathematical equation for the slinky in his patent materials.) It was Betty that masterminded the toy’s success. In 1960, Richard left his family behind and joined a religious cult. He died in 1974. Betty, a new single mother with six kids, took a big risk on the toy and waged the mortgage of their home to go to a toy show in New York in 1963, as Valerie Nelson reported for the Los Angeles Times in 2008. It was there that the toy caught a second wind, again selling out. The classic toy’s catchy jingle aired on television for the first time that year. After that, the toy sort of took on a life of its own.

During the Vietnam War, soldiers would sometimes use a Slinky as a portable, extendable antenna for their radios, fastening one end to themselves and tossing the other end over a tree branch to get a clear signal, according to Popular Mechanics. This bit of Slinky history was highlighted in “Invention at Play,” an exhibition that opened in 2002 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History before going on tour.

“That’s a very inventive story. This toy, made of metal wire, could be used in a very flexible way to solve a problem. You could throw it, carry it, stretch it,” says Smith. “Most people don’t think of that as invention, they just think that’s clever. But it’s definitely an inventive activity to look at a device near you and find another use for it.”

The Slinky has even gone to space. Astronaut Margaret Rhea Seddon demonstrated the Slinky’s behavior in zero gravity during a telecast from the Discovery Space Shuttle in 1985. ''It won't slink at all,'' Seddon said in the telecast. ''It sort of droops.''

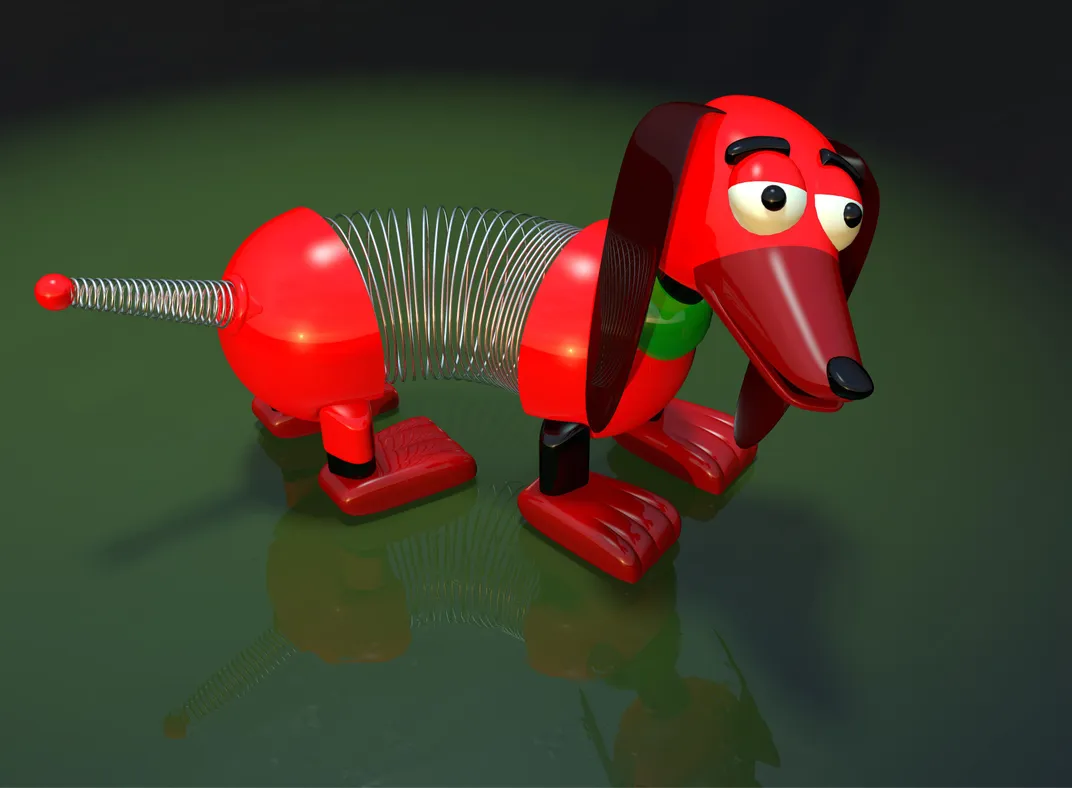

The Slinky took many forms too, most famously the Slinky dog, which was had been popular in mid-century homes before its cameo in the 1995 movie Toy Story. Before Toy Story, annual sales were only in the hundreds, reports Popular Mechanics. The movie boosted the sales of the toy, which James Industries patented in 1997, once again. The company manufactured 12,000 a year in February 1996 and numbers rose to 33,000 by April and 40,000 in July, according to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

When the Slinky was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame in 2000, more than 250 million had been sold to date. Smith emphasizes that the story of the Slinky should serve as inspiration for the next generation of inventors, noting that many get their start by creating toys. (That's true of the Lemelson Center for Invention and Innovation’s namesake Jerome Lemelson, who invented several toys before amassing 500 patents, including those for the VCR and Walkman.)

“If you want to inspire another generation, you want it to be accessible,” Smith explains. “Seeing people start with toys shows you don’t have to be Edison or Steve Jobs to be an inventor. It doesn’t have to be an iPhone. It can be something as simple as a Slinky.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)