The Accidental Invention of the Super Soaker

A leak in a heat pump gave rocket scientist Lonnie Johnson the idea for his powerful squirt gun

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/80/bd808ab0-9c75-478d-810b-200f17ee9959/super_soaker-edit.jpg)

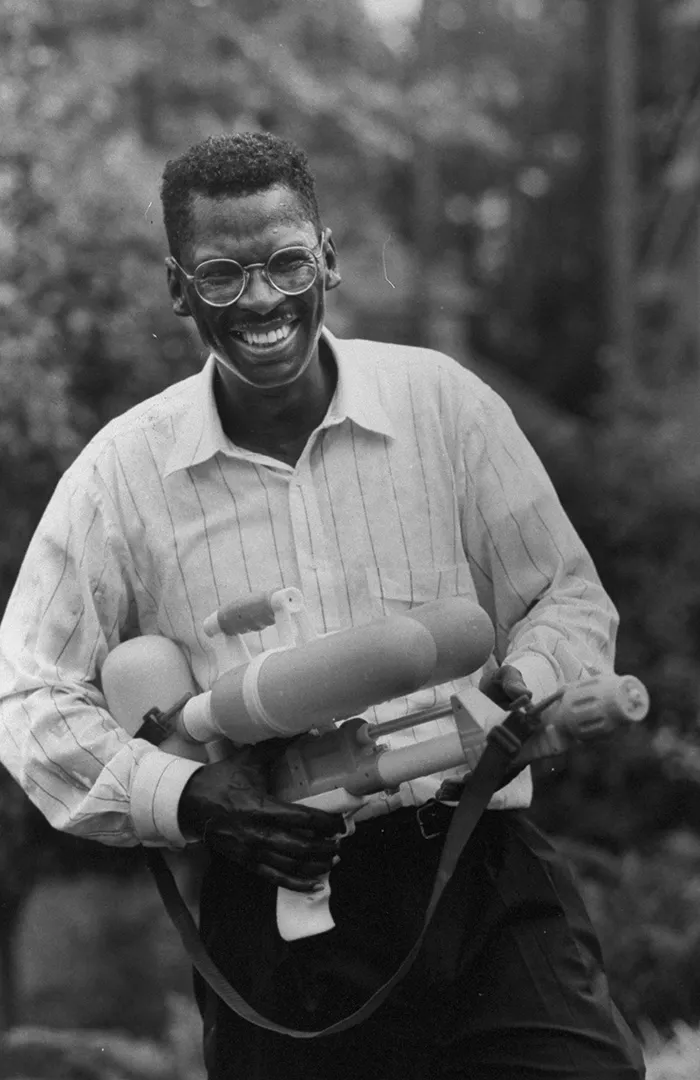

You might think it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to invent a squirt gun like the Super Soaker. But Lonnie Johnson, the inventor who devised this hugely popular toy that can drench half the neighborhood with a single pull of the trigger, actually worked on the Galileo and Cassini satellite programs and at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he helped develop the B2 stealth bomber.

Johnson is a prodigious creator, holding more than 120 patents on a variety of products and processes, including designs for film lithium batteries, electrochemical conversion systems, heat pumps, therminonic generators and various items to enhance battery production, including a thin-film ceramic proton-conducting electrolyte. In addition to serious-science inventions, Johnson has also patented such versatile and amusing concepts as a hair drying curler apparatus, wet diaper detector, toy rocket launcher and Nerf Blasters. Yes, that rapid-fire system with foam darts that tempts the child in all of us to mount ambushes on unsuspecting relatives and pets.

“I’m a tinkerer,” Johnson says. “I love playing around with ideas and turning them into something useful or fun.”

Johnson also came up with another interesting invention that is in common use today, though he didn’t capitalize on it. In 1979, while at the U.S. Air Force Space Missions Lab, he patented a device that optically reduces a binary code to scale, then uses a magnifying lens and sensors to retrieve the information. It is the basic technology used in CDs and DVDs today.

“I call it the big fish that got away because I was enjoying my day job so much,” he says. “I was really doing it just for fun and didn’t pursue it commercially.”

Like many inventions, the Super Soaker was the result of an accident. Johnson was at home in 1982 working on an idea for an improved heat pump – a device for heating and cooling that mechanically transfers heat to another source – when his creation sprang a leak. A burst of water shot across the room and Johnson immediately thought, “That would make a great squirt gun.”

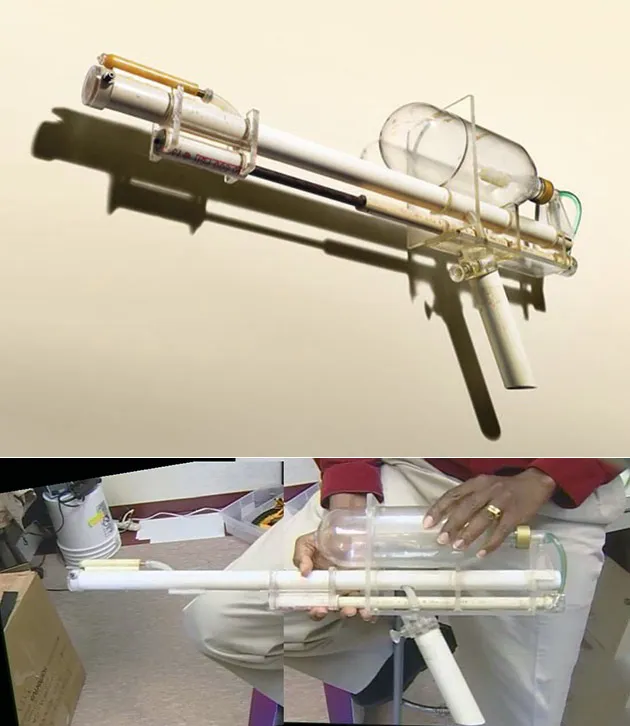

He worked on the concept and made a prototype from Plexiglas, PVC pipe, O-ring seats and other handy materials, including a two-liter soda bottle for the ample reservoir. Whatever parts he needed but couldn’t beg, borrow or steal, he made on a small lathe in his workshop at home. “That’s one of the advantages of being an inventor and tinkerer,” he says. “I have everything I need to make what I need.”

The original prototype, which Johnson still has, was a far cry from the squirt gun available on store shelves. The array of white PVC pipes and bulbous reservoir gave it a Star-Wars-ray-gun look. But as jury-rigged as it looked, the prototype could shoot: a compressed blast of water could carry up to nearly 40 feet.

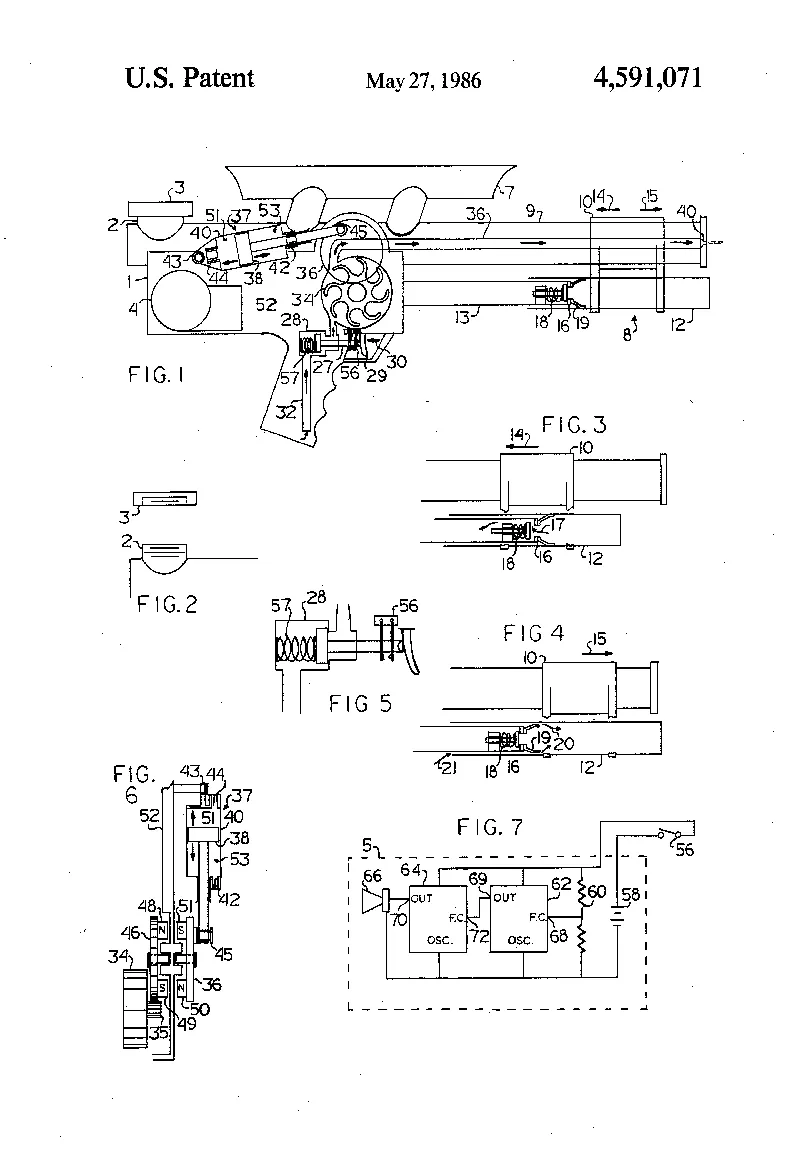

In 1986, Johnson received U.S. Patent 4,591,071 for a device simply titled “Squirt Gun.” As the abstract on his filing reads, “The squirt gun includes a nozzle for ejecting water at high velocity, a pressurization pump for compressing air into the gun to pressurize water contained therein, and a trigger actuated flow control valve for shooting the gun by controlling flow of pressurized water through the nozzle. A battery powered oscillator circuit and a water flow powered sound generator produce futuristic space ray gun sound effects when the gun is shooting.”

Johnson struggled for several years to find a company that could turn his idea into a commercial success. There were many skeptical responses and several false starts until finally in 1989 one toy manufacturer realized the potential for his drenching device. He licensed it to the Larami Corporation, which initially marketed the toy as the Power Drencher in 1990.

It took some tweaking and rebranding until the toy took off. It was relaunched as the Super Soaker with a clever and comical TV ad showing two young teens crashing a pool party while promising a “squirt gun of a higher caliber.” At a retail price of $10 each, sales soared to $200 million, catapulting it to the top-selling toy in the world in 1992. It has been one of the top-10 toys sold every year since then and has spawned numerous brand extensions for drenching friends and family.

The invention landed Johnson in the National Toy Hall of Fame. Christopher Bensch, vice president for collections and chief curator, says Johnson’s interstellar credentials give him elite status among inductees.

“He’s probably overqualified as toy inventors go,” he says. “After all, he is a rocket scientist. His invention was a rarified breakthrough because of its success. It ranks up there with the Slinky and Silly Putty. None of them were designed to be toys.”

Royalties from the Super Soaker and Nerf Blaster have enabled Johnson to pursue his dreams in a way he never imagined possible. Born nearly 70 years ago in the segregated South, the African American inventor has had to prove himself as a talented and capable scientist. His parents picked cotton on his grandfather’s farm and Johnson attended an all-black high school. He graduated from Tuskegee University before joining the U.S. Air Force as an engineer, then later working for NASA.

Johnson serves on the Board of Directors of FIRST, a nonprofit organization dedicated to inspiring young people to participate in science and technology. Don Bossi, FIRST president, is impressed by Johnson’s willingness to assist students interested in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

“Lonnie is a wonderful role model and mentor for aspiring STEM leaders like the students who participate in FIRST programs,” he says. “His story of persistence and overcoming obstacles inspires the next generation to follow in his curious and tenacious footsteps.”

While never intending to enter the toy business, Johnson has had the flexibility to move in new directions thanks to his inventions for children. These patents allowed him to start his own companies, Johnson Research and affiliates, and work on projects of his choosing.

“These products were huge successes,” Johnson says. “It certainly has had a big impact on my life. It’s enabling me to do the things I am doing now.”

Today, he is working on a solid-state ceramic battery that can store more energy than lithium ion batteries and the next-generation battery, lithium air, which can store 10 times the energy of current technology.

“Imagine driving a car cross-country on a single charge,” he says. “That’s what we hope to achieve with this technology.”

In addition, Johnson is working on a new water condenser that can pull moisture from ambient air. It will be powered by solar cells and is being designed for use in arid areas with high humidity.

True to his rocket-science roots, Johnson is also attempting to develop an energy converter technology that captures heat and converts it into electricity. It will use electro-chemistry to pull heat from engines, particularly the nuclear systems that power long space flights.

Unfortunately, there are no more toys in Johnson’s plans. That, however, could change with just one mistake, and a spark of his imagination.