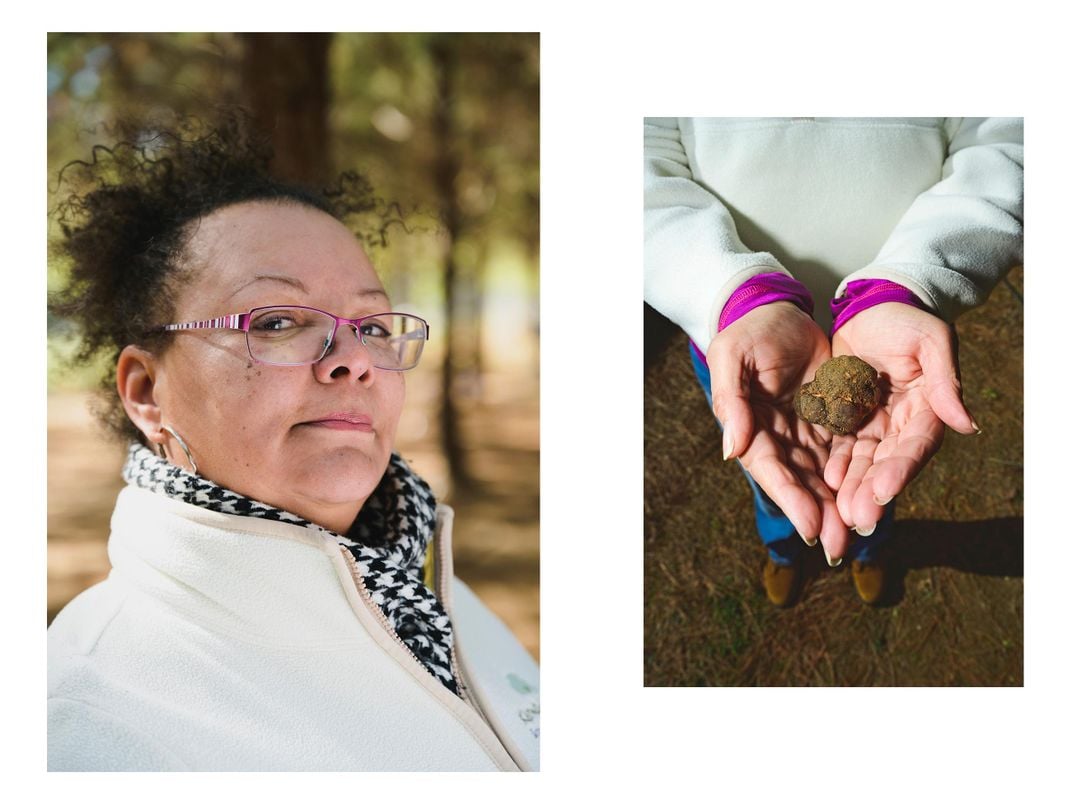

On a frosty February morning in North Carolina’s Piedmont region, the enterprising trio who has finally broken America’s strange truffle curse walks beneath orderly rows of loblolly pine, trying very hard not to step on the precious nuggets beneath their feet. Nancy Rosborough—the self-described “ghetto kid” from Washington, D.C., whose wobbly start-up, Mycorrhiza Biotech, might just be saved by the golf-ball-size tubers erupting out of the red dirt—looks around, trying to contain her emotions. After 15 years of struggling to bring her truffle-farming vision to life, she is staring at two acres of validation.

“Nobody believed in us,” she says, exchanging glances with Omoanghe Isikhuemhen, the mycologist who invented Mycorrhiza Biotech’s system for truffle cultivation. “They mocked us. They thought we were just some podunk people.”

She nods toward Richard Franks, Burwell Farms’ chief scientific officer, standing beside her in a Duke Blue Devils sweatshirt, a ball cap pulled over his short white hair. “And then we found one person who believed in us.”

Franks was expecting a few hundred truffles from this two-acre plot; instead, he is getting a few thousand, well beyond his rosiest projections. Truffles usually stay underground and have to be found by truffle-sniffing dogs. But these are so crowded that they are breaching the surface before fully ripe. Franks’ crew has been covering them up with nearby dirt and marking them with little flags, but they can’t keep up. The pine-needle-strewn ground is a minefield. Laddie, a yellow Labrador retriever and Burwell Farms’ truffle dog, is wandering the rows in a daze, nose overloaded.

“Watch your step,” Franks says to me, nervously eyeing my path. A lifelong Carolinian, he speaks in the clipped monotones of a Mission Control commander attempting to bring astronauts safely back to Earth. “Ever seen anything like this?”

No, I tell him, I haven’t. For the past two years, I’ve been hunting truffles around the world for a forthcoming book. I’ve followed some very muddy dogs through medieval Italian landscapes in the dead of night. I’ve dug black truffles in the arid oak plantations of the Spanish highlands. I’ve watched deals go down in Hungarian parking lots. I’ve seen stupendous truffle patches. But I’ve never seen a patch as productive as the one in these pines—especially not in America, where truffle farming has been a 20-year train wreck.

Despite millions of dollars of investment, many American truffle orchards have never produced any truffles at all, and only a handful produce more than a few pounds. But there are an estimated 200 pounds of truffles in this plot, making it one of the most productive truffle orchards the world has ever seen.

I mention this to Franks, and he nods slowly. At age 75, he keeps getting thwarted in his attempts to retire, and now this. “We did something right,” he finally concedes. “Now we have to figure out what it was.”

I turn to Isikhuemhen—everyone calls him Dr. Omon—who is sporting a wide smile beneath his blue kufi hat. Beatific as a Buddha, he has an unshakable faith in the sunny disposition of the universe. “The secret is this team,” he answers in English inflected with the honeyed tones of his native Nigeria. “The power is in this team that came together!”

When I ask for the source of his confidence, Isikhuemhen says, “I don’t want to blow my own trumpet, but when a blind man tells you he’s going to stone you, you know that his foot is on a stone.”

And that’s about all I’m getting out of him. When I ask probing questions about his new techniques, he just gives me a cagey smile. “That’s nothing to share in public.”

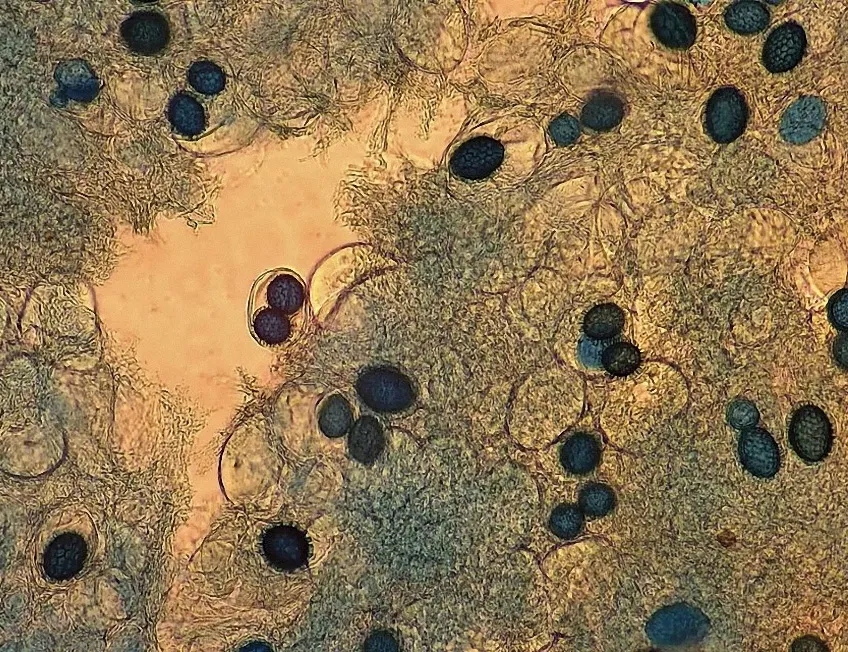

Like mushrooms, to which they are closely related, truffles are the fruiting bodies of a fungus that forms a partnership with trees, sheathing the tree roots in a net of cells known as mycorrhiza and feeding the trees water and micronutrients in exchange for sugars, which the trees make through photosynthesis. But unlike mushrooms, which rise above the surface, open their parasols, and let wind and water spread their spores, truffles stay underground—an adaptation to dry environments. Nestled in the earth, they have less of a risk of desiccating in a drought, but they do have a spore-dissemination challenge. They’ve solved it brilliantly by producing some of the most extraordinary scents in biology, complex cocktails of aroma that many animals, including humans, find irresistible. The animals dig up the truffles, eat them and spread the spores.

The relationship between plants and mycorrhizal fungi is both beautiful and essential—most trees can’t flourish without their fungal partners—but it’s also notoriously complicated. Even the best truffle scientists don’t understand all the nuances of the system, or the number of different organisms that might be involved.

All Isikhuemhen will say is that his innovation has something to do with “microbial dynamics,” and something to do with his growth media, which he uses to inoculate the pine seedlings with truffle spores before they get planted in the orchard. “It’s a secret mix that grows truffles five times faster than any other media. Its composition is very abnormal. Very. It came to me in a dream.”

He looks me right in the eye to show he’s serious. “It’s not the first time that’s happened to me. When you get such messages from the divine, you work with them.”

Before I can ask other questions, he deflects attention back to Franks. “But again, from the time the trees got to the field, it was this man. He took it to the next level.”

I look around the plot. Without a doubt, it is the cleanest, most orderly truffle farm I’ve ever seen. The trees are healthy and the ground is pristine. Along with Isikhuemhen’s secret sauce, that must be part of the reason for the eye-popping production.

But the other factor is the truffle itself. It’s the bianchetto, or “whitish” truffle, a different species from the famed white truffle of Italy and the black winter truffle of France (a.k.a. the Perigord, for the region that first made it famous). If the black winter is the Rolls-Royce of truffles, all silky luxury, and the white is the Lamborghini, a sexy rush, the bianchetto is more like the BMW—it doesn’t deliver the erotic crescendo of the white, but it still possesses most of the pheromonal zip at a much lower price. While the black winter sells for about $800 a pound, and the white goes for $3,000, the bianchetto comes in closer to $500.

But unlike the white, which has resisted every effort at cultivation, and the black winter, which is cultivated all over the world but struggles mightily in the States, the bianchetto seems to love the Southeast—at least judging by this plot.

With Franks’ permission, I search for a mature truffle. Most are still a pale beige, but here and there one has darkened to a sort of golden scrapple. I pluck one from the ground and hold it to my nose. My brain lights up with the scents of funk and garlic and things I have no name for. There is no pleasure more shivery than the aroma of a good truffle, and this is a good one.

Now we are about to find out if it is the one to conquer America. Rosborough and Isikhuemhen are hot properties, and a parade of agronomists is beating a path to Burwell Farms. If American trufficulture finally takes off, after several aborted launches, it will be because three outsiders from wildly diverse backgrounds were able to form a partnership as mutually beneficial as the one unfolding beneath our feet.

* * *

Truffles make mammals do strange things. They’ll make a boar stop short and snort the earth like a drug addict. They’ll make a flying squirrel ditch the safety of the treetops for a nutritionally marginal snack. And they’ll make a person forgo sleep for a nighttime hunt or, worse, plow a life’s savings into a truffle patch with only the vaguest hope of a return.

They accomplish this through a kind of sophisticated olfactory manipulation. Smell is the sense most intimately connected to memory and emotion in the brain, and truffles seem to play on this, making themselves both unforgettable and meaningful to people in ways that can be hard to articulate.

That power has made truffles one of the most prized gourmet foods in the world. Every autumn, thousands of people flock to Italy to experience fresh white truffles shaved tableside over their pasta and eggs, and to France to attend small-town truffle fairs, where the “black diamond” of Perigord is sold on the street like contraband. No other ingredient can so instantly lift a dish from ho-hum to extraordinary, and during truffle season hundreds of tons of the pricey nuggets are overnighted to eager chefs worldwide.

The art of truffling probably evolved from farmers observing their sows uprooting truffles whenever they could. Eventually, they trained their pigs for the hunt. But pigs love truffles too much and are difficult to reason with. Besides, truffle hunting is a secretive affair, and if you’re loading a 400-pound porker into the passenger seat of your Peugeot, everyone knows exactly what you’re up to. Long ago, most truffle hunters switched to dogs, which happily work for kibble.

Truffles were a wild food until the early 1800s, when a Provence farmer and truffle hunter named Joseph Talon noticed the black truffles he found were often growing near oak trees. He transplanted oak seedlings from beneath truffle-producing oaks onto his own land, and a few years later was delighted to find truffles beneath those trees. He continued planting acorns and transplanting seedlings until he had acres of truffle oaks, becoming the world’s first truffle farmer. The technique was rudimentary but effective. Talon got rich, and word got out.

In the mid-19th century, as the phylloxera epidemic destroyed vineyards in France, desperate growers turned to truffles for salvation. A wave of oak plantings led to a truffle boom that peaked around the end of the century, when France produced more than 1,000 tons of truffles per year, almost entirely black winter (Tuber melanosporum).

World War I brought that golden era to a crashing halt. Farmers went to war, farms were abandoned, and oak trees were cut down for more pressing needs. Some truffle farms staggered on, but World War II finished off most of the survivors.

Trufficulture revived in the 1970s, when French scientists finally solved the mysteries of black truffle propagation. Today’s techniques are refinements of their work. Oak and hazelnut seedlings are grown in sterile conditions in a greenhouse, where their roots are immersed in a thick solution containing millions of truffle spores. As the spores germinate, they form a complete mycorrhizal layer around the tree roots, like a glove over a hand, preventing any other fungi from getting a foothold. When the seedlings are planted, the fungi spread through the soil, feeding the trees, and, once mature, producing an annual crop of truffles.

At least, that’s how it’s supposed to work. Truffle cultivation is still as much art as science, and each farm guards its techniques and recipes. But the basics are well established, and black truffle farms have flourished in France, Italy and Spain since the 1980s, and more recently in Australia, New Zealand and Chile.

In the United States, however, no one has made it work for long. The reasons aren’t clear. Different soil? Climate? Predators? Pathogens? Or perhaps personalities? Most truffle orchards have been started by hobbyists—winemakers and other landed gentry who love the idea but perhaps don’t keep up with the maintenance for the eight to ten years it takes to see your first black winter truffles.

The only person who tasted commercial success was Tom Michaels, a mushroom expert who planted one of the nation’s first truffle orchards in Tennessee in the early 2000s. Michaels had a few good years, peaking at 200 pounds of truffles from his ten-acre orchard in 2009. But after that the Eastern Filbert Blight, a fungus that has destroyed most truffle orchards on the East Coast, wiped him out.

Today, the most productive Perigord orchard in the United States is on the Kendall-Jackson wine estate in Sonoma County, California, which produces about 35 pounds a year on ten acres. Only a handful of farms produce more than a few pounds, despite millions of dollars of investment. Most produce nothing.

Which is why all eyes in the truffle world are now on Burwell Farms and Mycorrhiza Biotech.

* * *

Growing up poor in Washington, D.C., Nancy Rosborough didn’t know a truffle from a tricycle. But she knew a bit about farming. Her mother had been raised on a small farm in Gibsonville, North Carolina, in the heart of tobacco country. The house was still in the family, and the rural landscape had always been a spiritual touchstone to the city kid, who went on to build a successful career as an information technology consultant. But over the years, as tobacco tanked, Rosborough had watched as Gibsonville was engulfed by the New South. “Dirt roads and farms turning into subdivisions,” she says. “Then you get Walmart and Ruby Tuesdays and you can’t afford the taxes.”

Rosborough was always looking for new crops that could revitalize the region’s farms, including her family’s. In 2005, her mother sent her a Washington Post article about North Carolina tobacco farmers experimenting with truffles. “Like everyone else, I thought, well, they grow on trees, how hard could it be?” She moved to the Gibsonville farm that same year and contacted a truffle tree supplier who explained that after planting the seedlings she’d have to wait a decade to get a real crop. That’s ridiculous, she thought. What kind of farmer could do that?

The more she looked into the truffle business, the dicier it seemed. Truffle-tree seedlings seemed to vary greatly in the amount of truffle mycorrhization on their roots, but the average farmer had no way of telling. Her IT career had taught her a lot about risk assessment, so she decided to start a lab that could analyze and certify the seedlings.

She approached Isikhuemhen, a mushroom expert at North Carolina A&T State University in nearby Greensboro. Isikhuemhen had grown up on a subsistence farm in rural Nigeria, hunting mushrooms with his family and hawking them in the market. The first in his family to attend college, he’d gone on to get his PhD in mycology. His family thought that was hilarious (“You went to college to study mushrooms?”), but he’d become a respected specialist in shiitake cultivation and had helped some of North Carolina’s tobacco farmers pivot to mushrooms.

Isikhuemhen had watched the nascent truffle industry with skepticism, and even a little bitterness. When the state of North Carolina put together a team of researchers to develop a black winter truffle industry, the Nigerian had been left out of the mix.

But maybe that was just as well. The closer Isikhuemhen and Rosborough looked at Tuber melanosporum, the more they thought its American prospects were limited. “That is a beast of a problem,” Isikhuemhen told me. Slow growing, finicky, outcompeted by too many native organisms, it was hard to make it work commercially. Besides, everybody was doing melanosporum. “Let’s do something different,” Isikhuemhen suggested.

They were intrigued by Tuber borchii, the bianchetto. Sure, it didn’t command the prestige or the prices of Tuber melanosporum, but it was supposed to produce a bigger crop in half the time, and it came ripe in spring instead of winter, meaning it would have no competition in the marketplace. Most important, it liked to grow on loblolly pines, the standard timber tree throughout the Southeast.

With grants from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center, they set up a lab and tackled bianchetto cultivation. Isikhuemhen visited bianchetto farms in Italy, observing what worked and what didn’t. At some point, he had his dream epiphany about microbial dynamics.

By 2010, they were achieving mind-blowing levels of mycorrhization on pine seedlings in their lab. They advertised. Not having enough capital to launch their own farm, they began looking for clients to buy their inoculated tree seedlings. They spoke at forestry conferences. They presented at the North American Truffle Growers Association. No dice. Everyone wanted to see an example of a successful orchard. They wanted hard numbers on pounds per acre.

“It was extremely frustrating,” Rosborough says. “We knew it worked. And nobody believed in us.”

After two years, Mycorrhiza Biotech had burned through its seed money and had nothing to show. “We had no customers,” Rosborough told me with a sigh. “We were tired. We decided to quit.” She stuck a for-sale sign on the lawn in front of the lab and called a liquidator to come get the equipment.

And that was when Rosborough received a mysterious phone message. “My employer has an interest in truffles,” said the stiff voice.

She didn’t bother calling back. “First of all, who talks like that?” Second, she was all too used to pretenders whose interest disappeared as soon as they learned it took $25,000 an acre to set up a truffle farm.

But the caller left a second message. His employer was still interested in truffles.

By the third call, she decided to call back. “We did our song and dance and told him it would be close to $50,000 to set up a two-acre orchard. And he didn’t flinch. I thought, ‘Who are these people?’”

The man on the other end of the line was Richard Franks, and his employer was Thomas Edward Powell III—a very familiar name in North Carolina. In 1927, Thomas Edward Powell II, a science professor at Elon College, founded a company called Carolina Biological Supply to provide plant and animal specimens to science teachers. The company went on to become a leading provider of teaching materials worldwide. Powell’s three sons then founded a diagnostics company called Biomedical Laboratories in a hospital basement in Burlington in 1969. After various mergers and acquisitions, Biomedical Laboratories became LabCorp, which is now the largest clinical diagnostics company in the world. LabCorp processes hundreds of millions of lab tests every year. It has 65,000 employees. And it’s worth an estimated $15 billion.

Rosborough called the liquidator and told him not to come just yet.

* * *

Richard Franks had worked for the Powell family his entire life. Both he and his father spent their careers at Carolina Biological Supply. After retiring in 2007, Franks had been managing some of Powell’s properties, including timber holdings.

One Sunday afternoon in 2010, he was settled into his den, watching an NFL game, when he received a phone call from the 78-year-old Powell. He had just had lunch with his interior decorator, who’d read about a truffle in Italy that grew beneath pine trees.

Powell owned hundreds of acres of pines in Warren County. Could he inoculate them with truffles? And could Franks manage the thing? See him at 8 o’clock in the morning.

Franks spent the rest of the afternoon giving himself an online crash course in truffles. He didn’t like what he saw. A lot of people had lost a lot of money. He didn’t want Powell to be the next. This is crazy, he thought. Then again, most of them weren’t working with the pine truffle, and they weren’t tree professionals. If there was one thing Franks knew how to do, it was grow good pines.

The first seedling supplier he called laughed at him when he said he wanted to grow Tuber borchii. “I consider those weeds,” the man told him.

Back to the internet. Up popped a single hit for a source of bianchetto-inoculated seedlings: Mycorrhiza Biotech. Unbelievably, the company was right in Burlington, less than two miles away. It seemed like a sign.

When Franks finally got Rosborough on the phone, they talked for three hours. His employer was interested in truffles. A lot of truffles. Was she interested?

Yes, she was interested.

Franks met with Rosborough and Isikhuemhen and peppered them with questions about timing and yield. “We really don’t know,” Isikhuemhen kept answering. “No one has tried these techniques on a commercial scale before.”

The honesty impressed Franks: “If anybody involved with truffles doesn’t use the term ‘I don’t know’ a half-dozen times in your first conversation, they probably have no idea what they’re talking about.”

He called Powell. “They think they can do it. I think they can do it. Do you want to do it?”

“Go for it,” said Powell.

In 2012, while Mycorrhiza Biotech was growing 1,100 inoculated loblolly seedlings in its greenhouse, Burwell Farms prepared two acres of ground to Isikhuemhen’s specifications. Any existing roots in the ground would already be impregnated with their own native mycorrhizal fungi, so they all had to be stripped away, down to eight feet. It took a bulldozer equipped with a massive root rake a year to comb the earth clean. Then the pH of the soil had to be raised from 5.7 to 7.3, a level that truffles love and few other organisms can tolerate. A procession of trucks plastered the ground with 15 tons of lime per acre.

In June 2014, they planted the seedlings, along with Isikhuemhen’s mysterious media, watered them hard and waited. They hoped to see their first truffles in the winter of 2018-19.

In December 2016, Isikhuemhen, Rosborough and Franks made the 90-mile drive to the farm for one of their regular site visits. On the way, Rosborough and Franks confessed to having doubts. Unproven techniques, unproven truffle. They were already the laughingstock of the truffle world.

Keep the faith, Isikhuemhen told them. “If you are born to do something, every road you take leads to what you are supposed to do. And you are naturally equipped with intuition and awe to find your way there.” He flashed his wide smile. “I’ll bet you a hundred dollars we find a truffle next year.”

They pulled up to the neat block of pine trees and stepped out into the cold. Isikhuemhen looked at the pines and grinned. They were now larger and more vigorous than any of the same age he’d seen in Italy. The truffles and the trees had taken to each other like long-lost siblings. He leaned over to Franks. “I take it back,” he whispered. “There are truffles here now.”

“How do you know?” Franks asked.

“I just know.”

They noticed an animal trail leading from the forest into the orchard. They followed it to where the ground had been scraped in an attempt to dig. Isikhuemhen slashed at the mat of weeds with his machete and pulled it back. Breaching the surface was the small white rump of a bianchetto truffle.

“It worked,” Rosborough whispered under her breath.

Isikhuemhen did some sort of a jig. Franks called Powell with the good news. From the sounds on the other end of the line, Powell may have been doing his own jig.

They found another dozen truffles that winter. Then four pounds the following year. Then 30 pounds in 2019, well before they were ready. They had no sales-and-marketing team. They had no distribution. Laddie had been trained to be rewarded with a tennis ball instead of food, which seemed like a good idea when they were dealing with a handful of truffles, but now every time he found one he wanted to play ball for ten minutes.

What on earth will 2020 bring? Franks wondered to himself. And that was before he knew about any of the things 2020 had in store for them.

* * *

Franks first realized something was up in October 2019, when he visited the orchard and saw the soil lumping up in hundreds of spots. Isikhuemhen did his jig again when he heard the news. “I knew it!” he sang. “Destiny!” Soon the truffles started breaching the surface, far too early in the season. Their aroma wouldn’t fully develop for several months, and they could be ruined by frost. Everywhere the farmhands dug up soil to cover the truffles, they uncovered other truffles on their way up. When they did pull out a truffle, they found others nested beneath.

By January they had flagged 3,000 truffles. Most weighed an ounce or two, but one cluster they nicknamed “The Brain” was nearly a pound. At first the aroma of the truffles was underwhelming, and chefs who received samples were not impressed, but by late February a Proustian pungency began to permeate the low orchard air. An old farmhand named David Crow supplanted Laddie, crawling through the pines on his hands and knees and shouting, “This one’s perfumin’ right here!” when he found a keeper.

This time, the pros were won over. “I think it’s a lovely truffle,” Olivia Taylor, the former president of the North American Truffle Growers Association, told me. “Some chefs are skeptical of it because they don’t know it, but others are really keen on it. And given the price point, it’s something that could do really well.”

It did. “Chefs ordered, and then they ordered some more,” Franks says. Gary Menes, of the Michelin-starred Le Comptoir in Los Angeles, tweeted that they were “Beautifully fragrant, sweet and delicious.”

And then, just when the stars had aligned, says Franks, “it all came to a screeching stop.” With Covid-19 lockdowns, the restaurant industry collapsed. “It’s a bad feeling when you’re looking at 30 pounds of truffles in your fridge, going nowhere, and you know there’s another 30 pounds coming right behind it.”

Burwell Farms froze its truffles. Though frozen truffles turn to mush if thawed, they can be shaved frozen over dishes and still impart aroma. The company also started selling direct to consumers, a lifesaver.

Thomas Edward Powell III doubled down on the future, Covid be damned. Burwell Farms has now planted five two-acre orchards, 5,500 trees in all. In a few years, it expects to be harvesting more than a thousand pounds of truffles a year. The original plot continued to produce in 2021, but record rainfall caused many truffles to rot before they were ripe. Barring other weather weirdness, 2022 looks promising.

Isikhuemhen and Rosborough are now bona fide stars in the world of truffles. “They took a chance on us, but it wasn’t as big a risk as they thought,” Rosborough says. “There’s nobody smarter than Dr. Omon, and can’t nobody outwork me. Come hell or high water, we were going to have truffles in this field.” She gives Franks credit for openness. “It’s been a good partnership for us. We’ve grown together. We’ve learned from each other.”

Isikhuemhen has new grants to expand his bianchetto program, and he’s testing sites in five North Carolina counties to learn which microclimates and soil dynamics are most conducive.

Mycorrhiza Biotech has nearly as many customers as it can handle. Rosborough bought the lot beside her lab to add a greenhouse and try to keep up with seedling orders.

For her, the ultimate sign of success came when she harvested 25 pounds of bianchetto truffles from the one-acre demonstration plot on her own family farm. Rosborough had planted the plot a year after Burwell Farms started theirs, but she hadn’t managed to keep up with the maintenance. Still, in 2021 it kicked in, and a steady stream of intrigued farmers and experts came calling.

But don’t congratulate her yet. “We were never doing this just to make money,” Rosborough says. “The goal has always been to get this technology into the hands of small farmers. If, in a few years, there are 50 farmers in each of the Southeastern states growing truffles on small plots and using that money to hold onto their land, then we can say it worked.”

This article was produced in collaboration with the Food & Environment Reporting Network, an independent, nonprofit news organization.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aa/43/aa43180f-71b6-474e-b75d-80c4f7527d6e/mobile_opener_-_jun2021_a09_truffles.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/70/c270850b-fcd0-4470-82a4-501322031e27/openernew.jpg)