AOL Instant Messenger Taught Us How To Communicate in the Modern World

As AIM sunsets, let’s reflect on its role in preparing people for today’s digital messaging methods

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/7d/747df266-0ef1-48a4-8bd7-e9377ab9108f/file-20171206-31525-1spjrov.jpg)

Toward the mid-1990s, America Online (by then going by its nickname, AOL) was the company through which most Americans accessed the internet. As many as half of the CD-ROMs produced at the time bore the near-ubiquitous AOL logo, offering early computer users the opportunity to surf the internet for a flat fee – at the time, US$19.99 for unlimited monthly access.

With nearly half of U.S.-based internet traffic flowing through AOL, the stage was set for a social evolution of sorts that shifted our collective relationship with technology and each other. AOL Instant Messenger, or AIM, was launched in May 1997 as a way for AOL users to chat each other in real time, via text.

The service’s Dec. 15 shutdown was announced, notably, on a new real-time text communication channel, Twitter. That is just one testament to AIM’s lasting effects on how people use technology to connect today.

All good things come to an end. On Dec 15, we'll bid farewell to AIM. Thank you to all our users! #AIMemories https://t.co/b6cjR2tSuU pic.twitter.com/V09Fl7EPMx

— AIM (@aim) October 6, 2017

Interaction, in private

AIM provided a space for discreet real-time interaction, with a layer of privacy not necessarily afforded by the home phone. In 1997, mobile phones were still remarkably expensive (the Nokia 6160 cost about $900 and the Motorola StarTAC cost nearly $1,000) and most could not send text messages. A few savvy tech users used pager-speak to communicate “143” (“I love you”) to their partners; a few others learned how romantic an email can be. But technology-based interactions were limited; they didn’t allow for real-time connection and required access to a landline (if you were on the road, likely a payphone) and a computer terminal.

AIM’s debut let friends and family connect in real time through their personal computers. Today, people might debate the proper balance between screentime and facetime in a society in which screens are seemingly everywhere. Yet communication research shows that screentime can complement rather than take away from facetime. For instance, scholars such as sociologist Danah Boyd argue that these venues were (and are still) critical for teenagers, who used AIM as a private space to engage each other and explore their own identities. For Boyd, communication technologies have provided teens with ways to socialize with each other away from structured adult supervision – something that today’s children find increasingly difficult.

Screen names and social interaction

While certainly not the first form of social interaction online, AIM established for many people one of the most critical elements of online identity: the screen name. In a text-only environment, screen names provide some of the only identifying cues for users and become the user’s embodied identity. Through these screen names, the AIM space felt like a social one, populated with real people and personalities rather than cold screens and text. In fact, many people still use their AIM screen name for other social media services, and many more became skilled at creating and maintaining more than one screen name.

Unlike face-to-face conversations, technologies such as AIM also allowed conversations to persist on-screen, both in the short term (during the chat) and in the long term (as an archived chat). This can affect how people see themselves, as well as their friends – as users revisit ongoing conversations, they can adapt their language (and even their self-presentation) accordingly.

Communication, sans cues

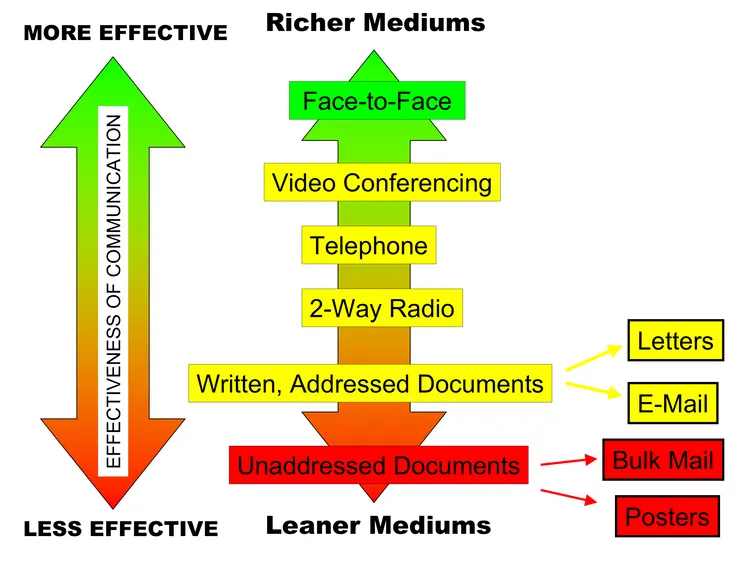

When it became popular, the text-only nature of AIM seemed anathema to social interaction – after all, how could people communicate emotions and feelings via text, stripped of the nonverbal cues (such as facial expressions and touch) that are so critical to human communication? People didn’t make the connection to the fact that it’s fairly common to have in-person interactions disrupted by nonverbal cues – such as when someone’s facial expressions don’t match the content of the conversation.

Communication scholar Joseph Walther theorized that a reason communication technologies such as AIM were capable of fostering meaningful social interaction is that users are able to overcome the lack of nonverbals. In fact, he says, systems like AIM made it easier to form relationships online, because people might be less critical or judgmental of each other, knowing that some social cues were missing – and focus more on the words of the conversation itself.

AIM is also where many people first saw and used emojis (then still called emoticons) to convey emotional context around ambiguous texts – adding a smiley or a frown-face to clarify what’s meant by a message such as “waiting for you to arrive.”

The platform also proved fertile for the development of text-speak abbreviations to save keystrokes – the sorts of “LOL” and “BRB” notes now ubiquitous in smartphone texting. While some feared that teenagers’ use of techno-gibberish would damage their language development, today’s millennials are reading more than any other generation. This use of language suggests they may have more – not less – sophisticated communications skills.

AIM as a legacy technology

As AIM shuts down at the end of 2017, the program can fairly call itself a success. It provided the earliest widespread platform for real-time text-based chat, honing users’ skills for the eventual adoption of smartphone-based texting and microblogs like Twitter. Indeed, as AOL’s own statement about the shutdown says, “The way in which we communicate with each other has profoundly changed” – in large part because of AIM.

Of course, for technology buffs still looking toward bygone technologies, another cue-lean, relational technology introduced in 1997 is making a comeback: The Tamagotchi digital pocket pets were re-released in November. Otherwise, those looking to revisit AIM after its closure might consider the video game “Emily is Away” to play through an interactive scenario with their high school bestie.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Nicholas Bowman, Associate Professor of Communication Studies, West Virginia University