The Archaeology of Wealth Inequality

Researchers trace the income gap back more than 11,000 years

When the last of the volcanic ash from Mount Vesuvius settled over Pompeii in A.D. 79, it preserved a detailed portrait of life in the grand Roman city, from bristling military outposts to ingenious aqueducts. Now researchers say the eruption nearly 2,000 years ago also captured clues to one of today’s most pressing social problems.

Analyzing dwellings in Pompeii and 62 other archaeological sites dating back 11,200 years, a team of experts has ranked the distribution of wealth in those communities. Bottom line: economic disparities increased over the centuries and technology played a role. The findings add to our knowledge of history’s haves and have-nots, an urgent concern as the gulf between the 1 percent of ultra-rich and the rest of us continues to grow.

“We wanted to be able to look at the ancient world as a whole and draw connections to today,” says Michael E. Smith, an archaeologist at Arizona State University, who took part in the study. The research is being published this month in Ten Thousand Years of Inequality, a book edited by Smith and Timothy Kohler of Washington State University.

Ten Thousand Years of Inequality: The Archaeology of Wealth Differences (Amerind Studies in Archaeology)

For the first time, archaeology allows humanity’s deep past to provide an account of the early manifestations of wealth inequality around the world.

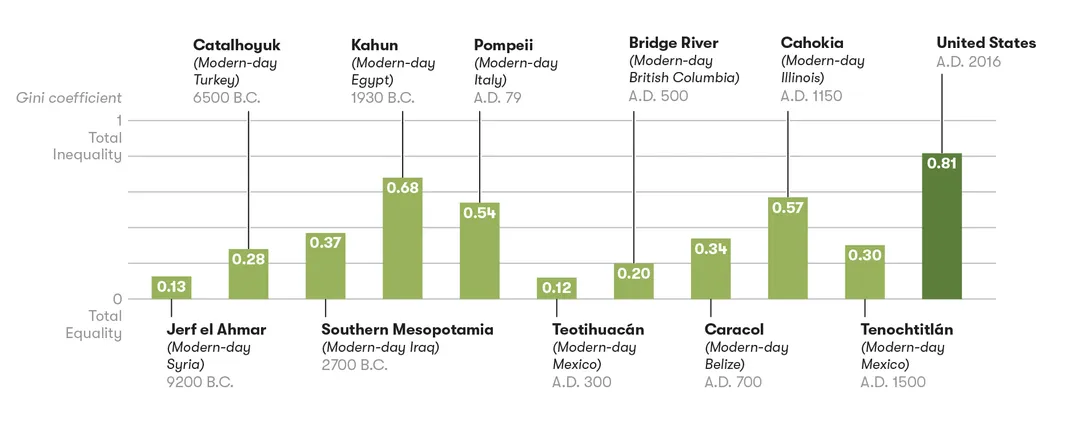

The idea of using house size as a proxy for economic status may not be revolutionary—a palace is bigger than a hovel, after all—but the researchers found a new way to gauge the economy of ancient settlements from structural measurements. For each site they calculated a value known to economists and policy wonks as the Gini coefficient, which quantifies how evenly wealth is distributed. In a population with a Gini coefficient of 0, everyone has the same economic resources; 1 represents maximum disparity. The Gini score of the United States, one of the most unequal countries, is about 0.81, while that of Slovakia is about 0.48.

How do past societies stack up? Hunter-gatherers, as scholars long hypothesized, tended to be the most equitable. But around 10,200 B.C., societies began to farm the land. Economic disparity edged up: farming enabled families to collect wealth and pass it on. In Europe and Asia, domestication of draft animals beginning around 10,000 years ago let some landowners cultivate ever larger areas, further concentrating wealth. That didn’t happen in the Americas until after Europeans exported that agricultural innovation in the 16th century.

The more technologically advanced a society was, the researchers say, the less equal it tended to be—a cautionary tale for our increasingly high-tech future.

Time Is Money

Comparing the size of dwellings at archaeological ruins, researchers found increasing wealth inequality over thousands of years. Technology accelerates the trend, first in the Old World and then in the New. For each site the experts calculated the Gini coefficient, a standard measure of wealth distribution. The gap between rich and poor in the United States is shown for reference.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.