The Beautiful Life Hacks in Hong Kong’s Back Alleys

In a new book, photographer Michael Wolf captures the ways inhabitants of the ultra-dense city carve personal space out of grim alleyways

In many cities, the term “back alley” conjures unsavory images—drug deals, muggings, rat infestations. But in Hong Kong, with its high population density and low crime rate, working class citizens use back alleys as a sort of extended living space.

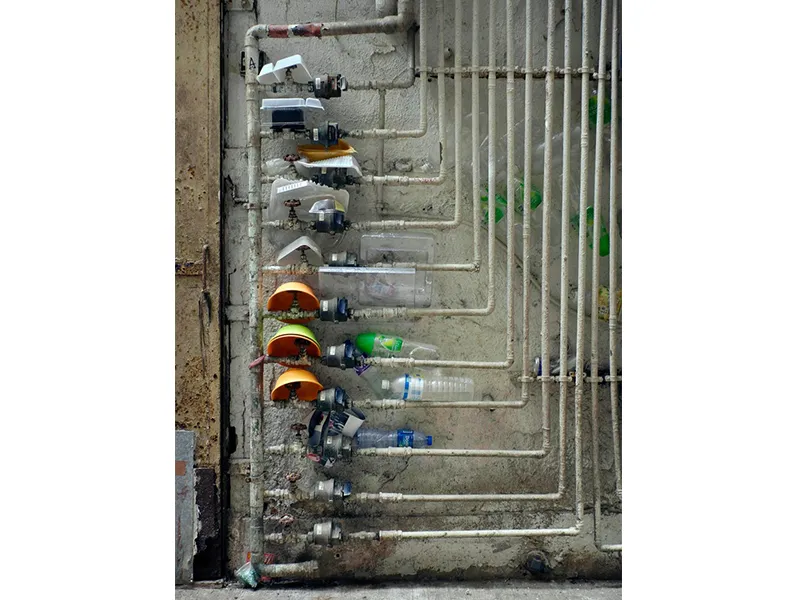

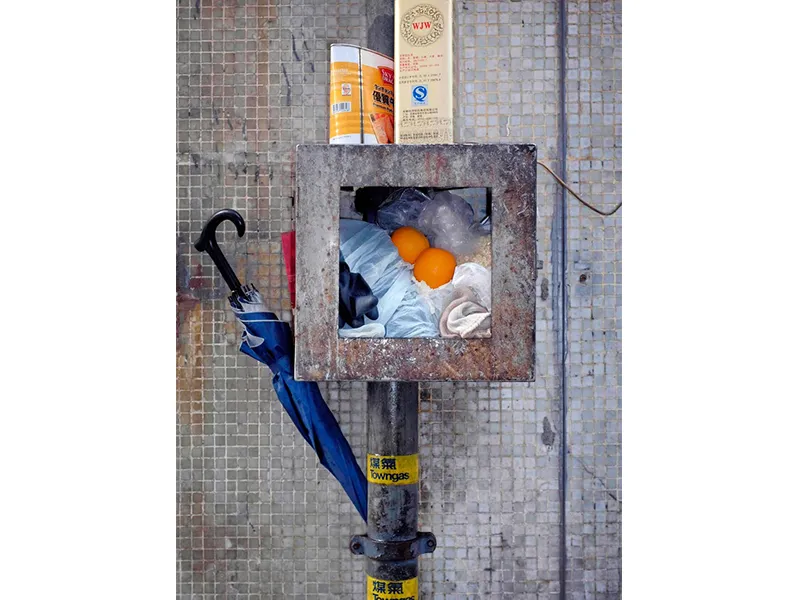

Michael Wolf, a German-born photojournalist turned fine art photographer who has lived in Hong Kong for two decades, has been chronicling these back alleys for years. Now, his new book, Informal Solutions, provides a record of just how innovative Hong Kongers can be when it comes to urban space.

I meet Wolf at his studio in Chai Wan, an industrial area on the eastern edge of Hong Kong Island, its warehouses and factory buildings slowly becoming populated by artists and designers. Though Wolf originally settled here to use Hong Kong as a base for assignments in mainland China, he's come to be fascinated with the city's aesthetics and culture of density—tower blocks so massive and symmetrical they look computer-generated, plants growing from cracks in the cement, one-room apartments packed to the gills with all their residents' earthly possessions. Hanging on the studio wall are various photos from Informal Solutions, detail shots of creative alley use in action.

“You have so little private space here you tend to make public space private by repurposing it,” Wolf says. “[Back alleys are] a unique aspect of the Hong Kong identity.”

In this city of 7 million, the average person has just 160 square feet to his or herself, compared to 832 in the United States. The space shortage is driven by exorbitant housing prices. Hong Kong was recently named the most expensive housing market in the world for the sixth year in a row, with the average apartment costing 19 times the annual median income. With young people unable to afford to rent or buy their own places, many are forced to live with their parents or other family members well into their 20s and 30s. Some of the city’s poorest residents live in so-called “cage homes,” subdivided apartments barely large enough for a bed and a hot plate.

In such conditions, space-starved citizens look outward for breathing room and solitude. Hong Kong’s vast network of narrow alleys, a vestige of 19th century Southern Chinese urban design, provide just that. Workers use the alleys for smoke breaks, stashing plastic stools behind air conditioning units and hiding cigarette packs in grates. Residents use their alleys as extra closet space, balancing pairs of shoes on pipes or hanging laundry from coat hangers suspended from window grates. People also beautify these often grimly gray and tiled alleys with flowerpots, turning unloved public space into makeshift gardens.

But these back alleys are at risk, Wolf says. The government is trying to clear some alleys to create better pedestrian flow in some of the city’s most dense districts. A recent HK $1 million (about US $128,000) pilot project in Hong Kong's Kowloon area involved hiring artists to paint alley walls to make them more attractive as thoroughfares. Though the murals will make the alleys more appealing to some, Wolf worries they're losing their character and utility for the city's working class.

“They [the government] call it face lifting. I call it sterilizing,” Wolf says. “Once they’re cleaned up, they become boring.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)