This Bioplastic Made From Fish Scales Just Won the James Dyson Award

British product designer Lucy Hughes has invented a biodegradable plastic made from fish offcuts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/87/6487b0bc-29ea-46b1-bef9-ab9ee01fe97c/marinatex-lucy_hughes.jpg)

Most people look at fish guts and think, “eww.”

Lucy Hughes looked at the bloody waste from a fish processing plant and saw opportunity.

Then a student in product design at the University of Sussex, Hughes was interested in making use of things people normally throw away. So she arranged to visit a fish processing plant near her university, on England’s southern coast.

She came away a bit smelly—“I had to wash even my shoes,” she says—but inspired. After tinkering with various fish parts, she developed a plastic-like material made from scales and skin. Not only is it made from waste, it’s also biodegradable.

The material, MarinaTex, won Hughes this year’s James Dyson Award. The £30,000 (nearly $39,000) award is given to a recent design or engineering graduate who develops a product that solves a problem with ingenuity. Hughes, 24, beat out 1,078 entrants from 28 different countries.

Hughes, who grew up in suburban London, has always loved to spend time near the ocean. As a budding product designer—she graduated this summer—she was disturbed by statistics like 40 percent of plastic produced for packaging is only used once, and that by 2050 there will be more plastic in the sea by weight than fish. She wanted to develop something sustainable, and figured the sea itself was a good place to start, given that the University of Sussex is outside the beach town of Brighton.

“There’s value in waste, and we should be looking towards waste products rather than virgin materials if we could,” Hughes says.

Once Hughes decided to work with fish skin and scales, she began searching for a binder to hold the material together. She wanted to keep everything local, so she began experimenting with seaweed and chitosan from shellfish shells, using her own kitchen as a lab. She tried more than 100 combinations, drawing insight and motivation from the global bioplastic community, where scientists share ideas and formulas freely for the greater good. Eventually she settled upon red algae as a binder.

“I was learning it all as I went along, but not being deterred by things that didn’t work,” Hughes says.

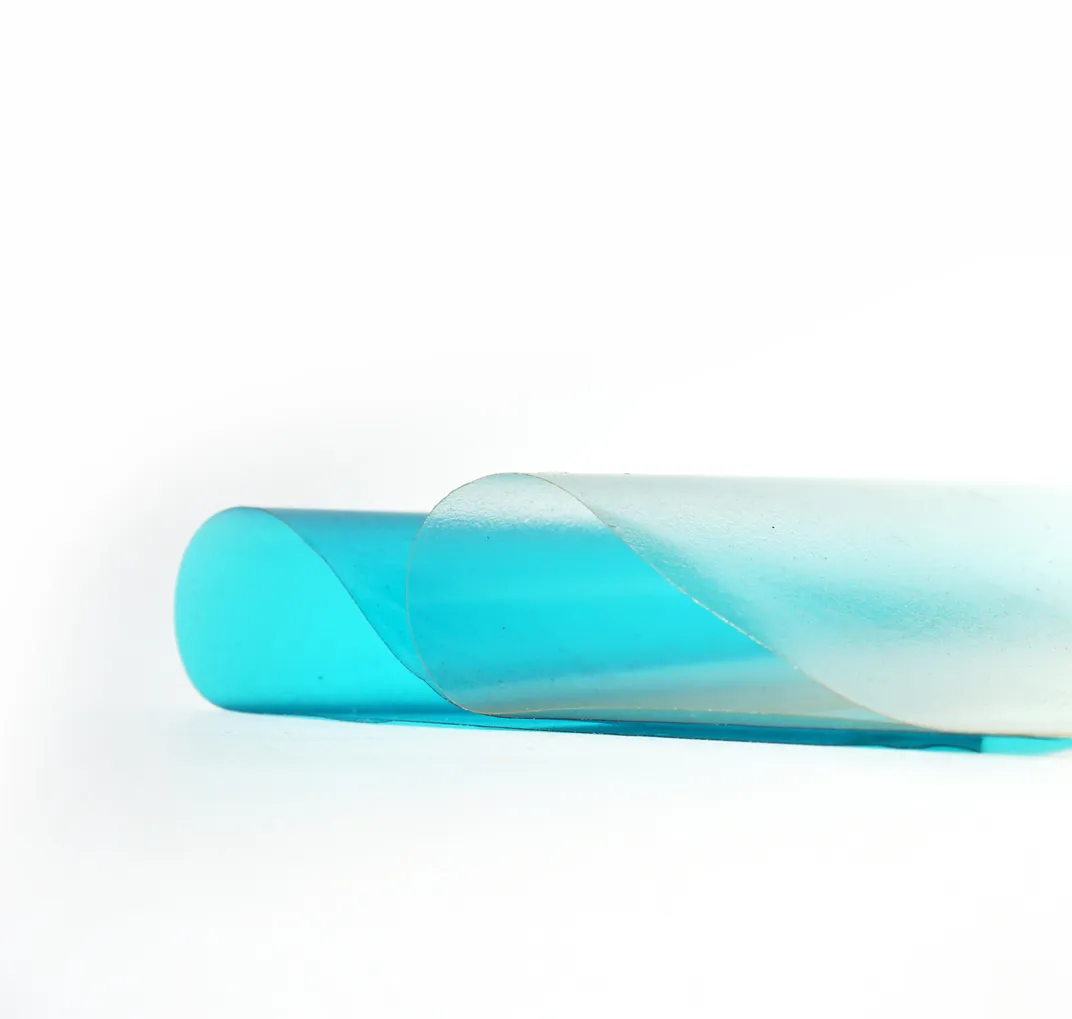

The resulting product is strong, flexible and translucent, with a feel similar to plastic sheeting. It biodegrades on its own in four to six weeks, which gives it a major sustainability advantage over traditional bioplastics, most of which require industrial composters to break down. In addition to utilizing materials that would otherwise be thrown away, the production process itself uses little energy, since it doesn’t require hot temperatures. One single Atlantic cod fish produces enough waste for 1,400 MarinaTex bags.

“Young engineers have the passion, awareness and intelligence to solve some of the world’s biggest problems,” said British inventor James Dyson, the contest’s founder, in a press release. “Ultimately, we decided to pick the idea the world could least do without. MarinaTex elegantly solves two problems: the ubiquity of single-use plastic and fish waste.”

Runners-up in the Dyson Awards include Afflo, an A.I.-powered wearable for monitoring asthma symptoms and predicting triggers, and Gecko Traxx, a wheel cover to allow wheelchair users to roll on beaches and other off-road terrain.

Hughes hopes to secure government grants to further develop MarinaTex. Since the product is made differently than plastic, it will require new manufacturing infrastructure. Hughes sees MarinaTex being used initially as a food packaging material like a bakery bag.

“The long-term goal is to get this to market and educate consumers and manufacturers on more sustainable options,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)