A Brief History of the Stoplight

How a bright idea shaped our cities and gave the go-ahead to our love affair with the car

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/67/c0678f8f-32a9-4d74-a57c-82519e2eb595/may2018_a02_prologue.jpg)

Driving home from a dinner party on a March night in 1913, the oil magnate George Harbaugh turned on to Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue. It was one of the city’s busiest streets, jammed with automobiles, horse-drawn carriages, bicyclists, trolleys and pedestrians, all believing they had the right of way. Harbaugh did not see the streetcar until it smashed into his roadster. “It is remarkable,” the local newspaper reported, “that the passengers escaped with their lives.”

Many others wouldn’t. More than 4,000 people died in car crashes in the United States in 1913, the same year that Model T’s started to roll off Henry Ford’s assembly line. The nation’s roads weren’t built for vehicles that could speed along at 40 miles an hour, and when those unforgiving machines met at a crowded intersection, there was confusion and, often, collision. Though police officers stood in the center of many of the most dangerous crossroads blowing whistles and waving their arms, few drivers paid attention.

A Cleveland engineer named James Hoge had a solution for all this chaos. Borrowing the red and green signals long used by railroads, and tapping into the electricity that ran through the trolley lines, Hoge created the first “municipal traffic control system.” Patented 100 years ago, Hoge’s invention was the forerunner of a ubiquitous and uncelebrated device that has shaped American cities and daily life ever since-—the stoplight.

Hoge’s light made its debut on Euclid Avenue at 105th Street in Cleveland in 1914 (before the patent was issued). Drivers approaching the intersection now saw two lights suspended above it. A policeman sitting in a booth on the sidewalk controlled the signals with a flip of a switch. “The public is pleased with its operation, as it makes for greater safety, speeds up traffic, and largely controls pedestrians in their movements across the street,” the city’s public safety director wrote after a year of operation.

Drive: The Definitive History of Driving

Beginning with the development of the first vehicles powered by an internal combustion engine, "Drive" explores the early glamour of driving, motor sport, and car design, and looks at how the automobile has shaped the modern world.

Others were already experimenting with and improving upon Hoge’s concept, until various inventors had refined the design to the one that controls traffic and raises blood pressure today. We have

William Potts, a Detroit police officer who had studied electrical engineering, to thank for the yellow light, but as a municipal employee he could not patent his invention.

By 1930, all major American cities and many small towns had at least one electric traffic signal, and the innovation was spreading around the world. The simple device tamed the streets; motor vehicle fatality rates in the United States fell by more than 50 percent between 1914 and 1930. And the technology became a symbol of progress. To be a “one stoplight town” was an embarrassment. “Because of the potent power of suggestion, [or] a delusion of grandeur, almost every crossroad hamlet, village, and town installed it where it was neither ornate nor useful,” the Ohio Department of Highways grumbled.

An additional complaint that gained traction was the device’s unfortunate impact on civility. Long before today’s epidemic of road rage, critics warned that drivers had surrendered some of their humanity; they didn’t have to acknowledge each other or pedestrians at intersections, but rather just stare at the light and wait for it to change. As early as 1916, the Detroit Automobile Club found it necessary to declare a “Courtesy Week,” during which drivers were encouraged to display “the breeding that motorists are expected to manifest in all other human relations.” As personal interactions declined, a new, particularly modern scourge appeared—impatience. In 1930, a Michigan policeman noted that drivers “are becoming more and more critical and will not tolerate sitting under red lights.”

The new rules of the road took some getting used to, and some indoctrination. In 1919, a Cleveland teacher invented a game to teach children how to recognize traffic signals, and today, kids still play a version of it, Red Light, Green Light. Within a few decades, the traffic light symbol had been incorporated into children’s entertainment and toys. Heeding the signals has become so ingrained that it governs all kinds of non-driving behavior. Elementary schools put the brakes on bad behavior with traffic light flashcards, and a pediatrician created the “Red Light, Green Light, Eat Right” program to promote healthful eating. Sexual assault prevention programs have adopted the traffic light scheme to signal consent. And the consulting firm Booz Allen suggested in 2002 that companies assess their CEOs as crisis (“red light”), visionary (“green light”) or analytical (“yellow light”) leaders. You can even find the colorful cues on the soccer field: A referee first issues a yellow warning card before holding up the red card, which tells the offending player to hit the road, so to speak.

In a century the traffic light went from a contraption that only an engineer could love to a pervasive feature of everyday life—there are some two million of them in the United States today—and a powerful symbol. But its future is not bright. Driverless vehicles are the 21st-century’s Model T, poised to dramatically change not only how we move from place to place but also our very surroundings. Researchers are already designing “autonomous intersections,” where smart cars will practice the art of nonverbal communication to optimize traffic flow, as drivers themselves once did. Traffic lights will begin to disappear from the landscape, and the new sign of modernity will be living in a “no stoplight town.”

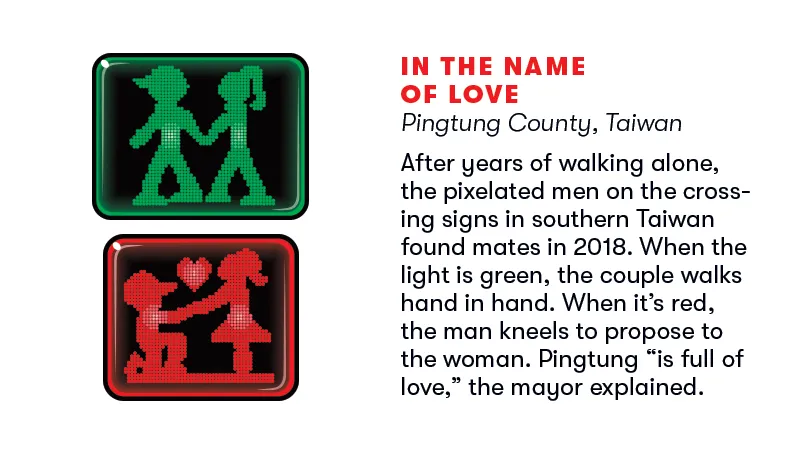

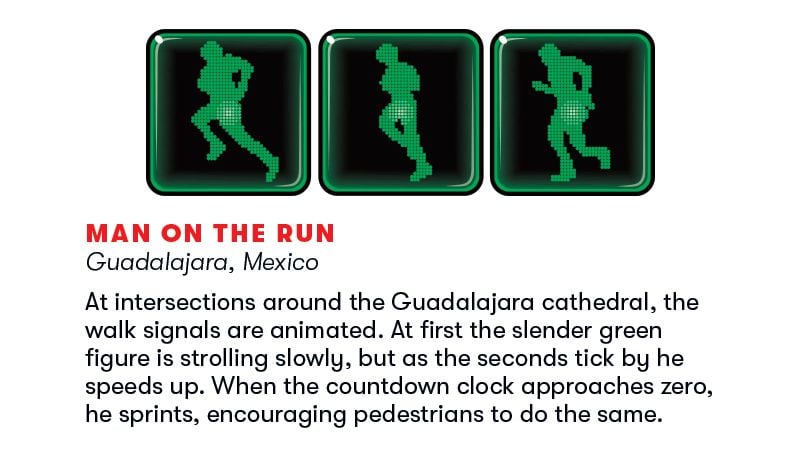

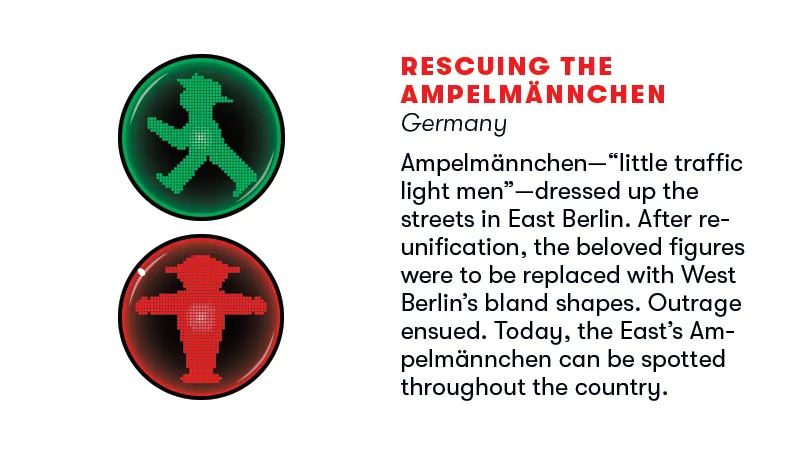

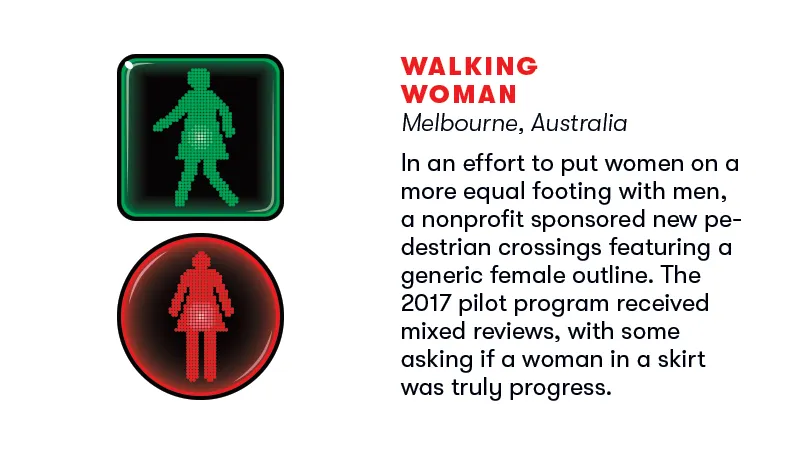

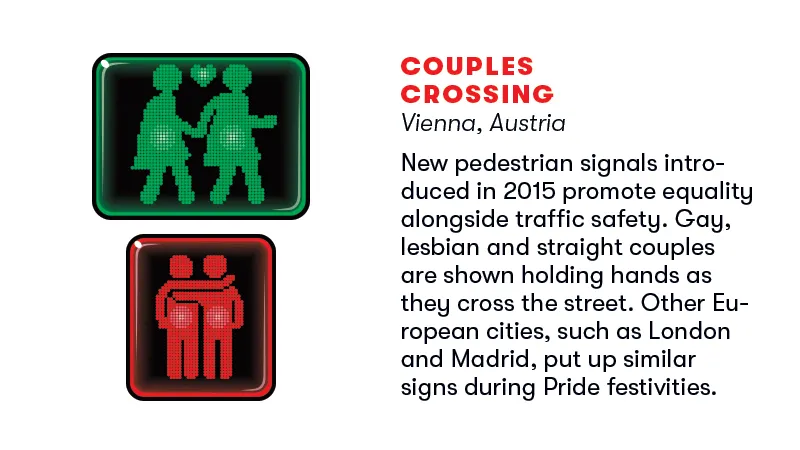

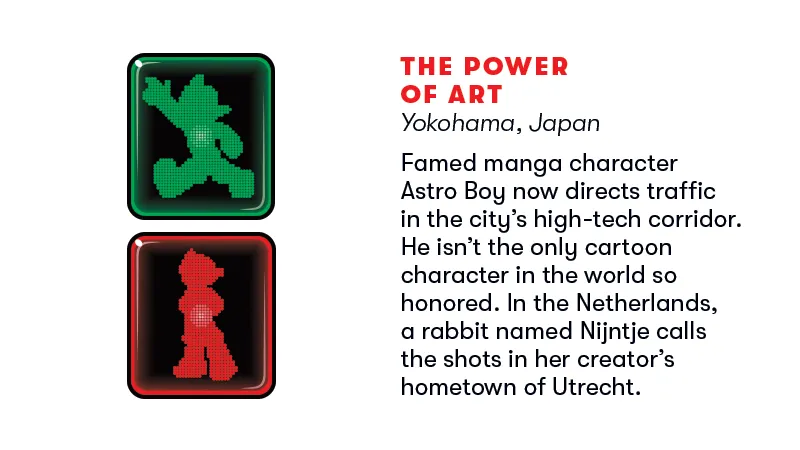

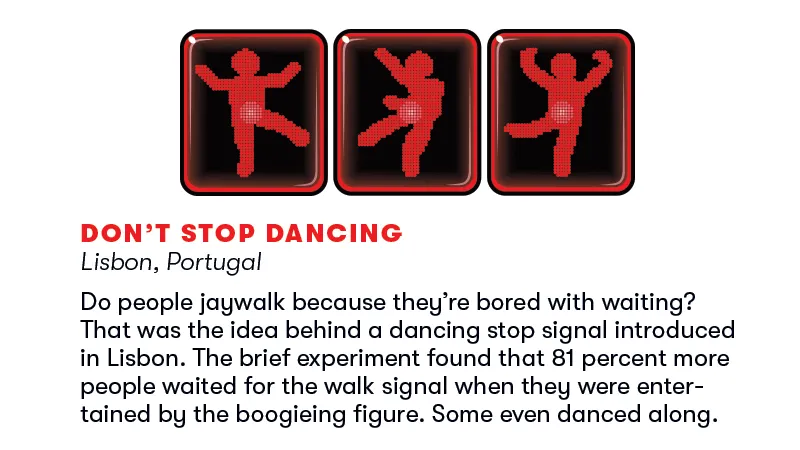

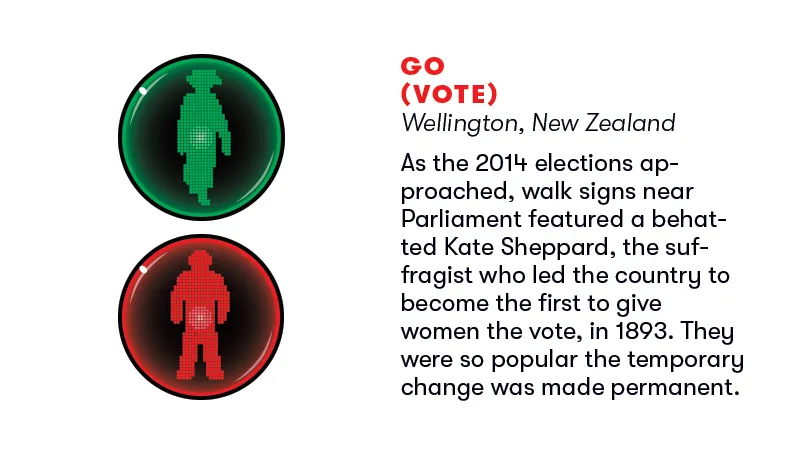

Should I Stay or Should I Go?

U.S. crosswalk signals are downright pedestrian. but others are so clever they’ll stop you in your tracks.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.