Can This App Predict Your Headache?

Migraine Buddy is one of a growing number of apps that use big data to help consumers manage their health issues

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/84/b784a0b7-8870-4488-a319-df1c79a9f27f/woman-asleep-smart-phone.jpg)

Like 36 million other Americans, I get migraines—throbbing headaches that often include strange sensory symptoms and sensitivity to light, sound and smells. Migraineurs (as sufferers are called) often spend enormous amounts of time and effort trying to figure out the “triggers” for their headaches. Common triggers include lack of sleep, caffeine (too little or too much), alcohol, aged meats and cheeses, and sudden weather changes.

Over the years, I’ve worked out that my triggers include dehydration, long plane flights, skipping my morning coffee and eating too much dairy. But despite doing my best to stay hydrated and caffeinated and to moderate my ice cream consumption, migraines pop up unexpectedly multiple times a month.

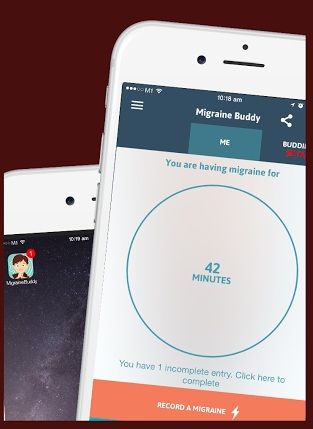

So I was personally curious to read about a new app called Migraine Buddy, which claims to predict migraines with 90 percent accuracy. The free app, created by Singaporean health data company Healint, uses a combination of active and passive data to understand individual migraine patterns.

For the active data portion of the app, users record each migraine they have, answering questions about pain intensity, where they are in their menstrual cycle (if they’re women, obviously), and where they were when the pain started (work, home, school, etc). It asks the users to guess the trigger for this particular headache. Preset triggers include anxiety, stress, physical exertion, processed food and lack of sleep, or users are allowed to add their own. It then asks whether the user had any physical or mental symptoms before the pain started—common pre-migraine “aura” symptoms include fatigue, weakness, visual disturbances and tingling in the head or neck.

None of this is dramatically different than other migraine recording apps. iHeadache, for instance, is an electronic headache log that tracks a user's triggers. What’s unique about Migraine Buddy is the passive data portion—that is, the part that requires no user input. The app learns when you sleep based on your phone use habits and creates an automatic sleep diary. Using the phone’s location systems, it files away information about the weather in your current locale. Changes in temperature and barometric pressure are triggers for many people.

This phone-generated data is important, as people’s own recall of these things is highly imperfect, says Veronica Chew, co-founder of Healint. “For example, if I would ask you how did you sleep last week, how would you answer that?” Chew asks.

Good question. I can barely remember how I slept last night.

Migraine Buddy, which was built based on input from neurologists and neuroscientists, could be useful to migraineurs in a variety of ways, Chew says. It could help them identify triggers. It could help them see how well their medications are working. It could be useful to show to doctors, so they can understand the extent of their patients’ problems. Eventually, once the app has been fed enough data, it can tell users when they might expect to get another migraine.

Over time, with user data, Healint hopes to refine its understanding of migraine causes and demographics. At present, Migraine Buddy has some 200,000 users around the world. The international nature of its data pool means Healint can make some interesting demographic observations. More men report migraines in Japan than in other countries, for example. But, in general, women have migraines three times as much as men. Japanese users are also more likely than users in other countries to report “stress” as a cause of migraines, which fits with the nation's reputation for working hard and relaxing little. Japanese sleep less than people of other nationalities and take an average of only 9 days of vacation each year.

“We can almost think of it as a real live clinical study,” Chew says.

It is a growing phenomenon to use big data collected by mobile apps for health purposes. Wearables like FitBit and the Apple Watch collect fitness data coveted by public health researchers; future wearables will likely collect everything from pulse to temperature to the contents of a user’s sweat. A mobile app and sensor combo called Propeller helps patients track symptoms of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), alerting healthcare providers of patients who need a higher level of attention. The location-tracking sensor, which users attach to their inhalers, provides a picture of where in the world people are having the most trouble with asthma and COPD, potentially offering clues about environmental factors that trigger attacks. An app called One Drop lets diabetics share information and take advantage of data-generated tips. Though some consumers have raised questions about security and privacy about using patient data this way, there seems to be no stopping this wave of new apps.

As for whether Migraine Buddy will help me track my migraines, it’s too early to say. So far I’ve recorded one headache (a one out of ten on the app’s pain scale, fortunately), which was clearly caused by skipping my morning java. But I'm hopeful it will allow me to identify some of my less obvious triggers. Clowns? The smell of croissants? Donald Trump’s voice?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)