Can Architecture Help Solve the Israeli-Palestinian Dispute?

The key to bringing these nations together in peace may be to first think of the territories as moveable pieces

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Architects-Save-Israeli-Palestinian-Dispute-631.jpg)

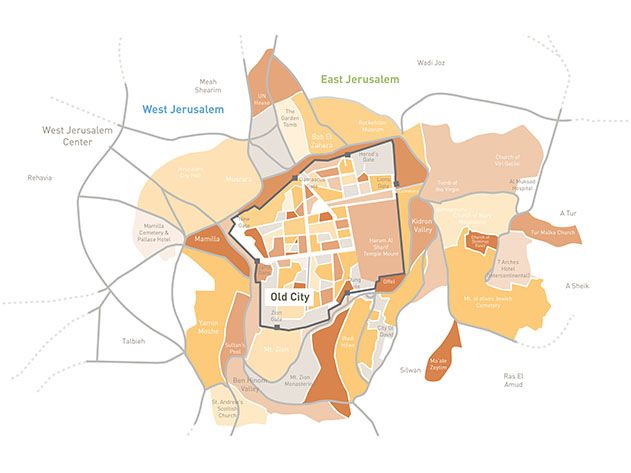

It’s 2015, and peace has finally come to the Middle East. Tourists stream to the Old City of Jerusalem from Israel and the new state of Palestine, passing through modern border crossings before entering the walls of the ancient site. Jerusalem has been divided, but creatively: the city’s busiest highway is used to separate the Jewish half of Jerusalem from the Palestinian one, the the border between the countries situated unobtrusively along the road’s median.

Both ideas were developed by a pair of young Israeli with an unusually practical approach to peacemaking. Yehuda Greenfield-Gilat and Karen Lee Bar-Sinai, both 36, have spent years working on highly specific ideas for how policymakers could divide Jerusalem between Israel and Palestine without doing permanent damage to the delicate urban fabric of the city.

The architects say their top priority is to prevent Jerusalem from being divided by barbed wire, concrete walls and machine gun batteries. That was the dire reality in the city until 1967, when Israeli forces routed the Jordanians, who had controlled Jerusalem’s eastern half since the Jewish state’s founding in 1948. All of Jerusalem, including the Old City, has been under full Israeli sovereignity ever since. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu insists that will never change. Jerusalem, he said in July, is “Israel’s undivided and eternal capital.” Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas said he will accept nothing less than a partition of the city that leaves its eastern half, and much of the Old City, under Palestinian control.

Greenfield-Gilat and Bar-Sinai have mapped out where the border between East and West Jerusalem would go and made detailed architectural renderings of what it would look like. They’ve even designed some of the individual border crossings that would allow citizens of one nation to pass into the other for business or tourism. They are trying to take big-picture questions about the future of the city and ground them in the nitty-gritty details of what a peace deal would actually look and feel like.

“We’re trying to fill the gap between the broad stroke of policymaking and the reality of life on the ground,” says Bar-Sinai, who recently returned to Israel after a yearlong fellowship at Harvard University. “Only thinking about these questions from the 30,000 foot high perspective isn’t enough.”

Her work with Greenfield-Gilat begins with the premise that the heavily-fortified border crossings currently in use across the West Bank – each guarded by armed soldiers and equipped with mechanical arms that look like those found in American toll booths – would destroy Jerusalem’s unique character if they were imported into the capital.

Instead, the two young architects have tried to blend the new border crossings into their surroundings so they stand out as little as possible. In the case of the Old City, which contains many of the holiest sites of Judaism, Islam and Christianity, that approach calls for situating the structures just outside the walls of the ancient site so its architectural integrity is preserved even as Israeli and Palestinian authorities gain the ability to move visitors through modern security checkpoints that resemble those found in airports. Once in the Old City, tourists would be able to move around freely before leaving through the same border crossings that they had come in through.

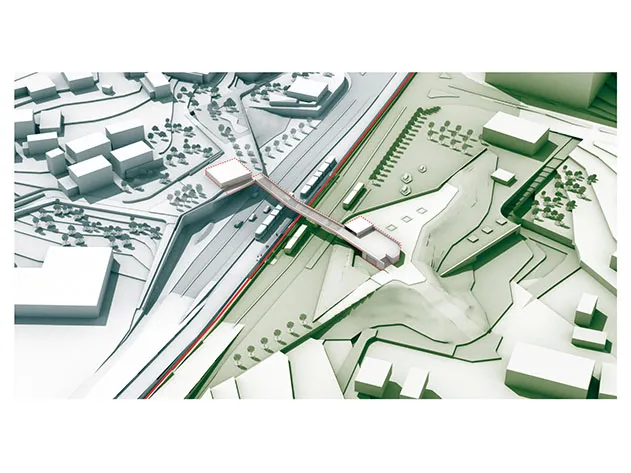

The two young architects have also paid close attention to detail. Their plan for turning Jerusalem’s Route 60 into the border between the Israeli and Palestinian halves of the city, for instance, includes schematics showing the motion detectors, earthen berms, videos cameras and iron fences that would be built on top of the median to prevent infiltration from one state to the other. A related mock-up shows a graceful pedestrian bridge near the American Colony Hotel in East Jerusalem that would arc over the highway so Israelis and Palestinians could enter the other country by foot.

Greenfield-Gilat and Bar-Sinai’s work is taking on new resonance now that Israeli and Palestinian negotiators have returned to the table for a fresh round of American-backed peace talks, but it has been attracting high-level attention for several years. The two architects have briefed aides to retired Senator George Mitchell, the Obama administration’s chief envoy to the Israelis and Palestinians, and other senior officials from the State Department, White House and Israeli government. In 2008, then-Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert presented their sketch of the American Colony bridge to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas as an example of what the separation of Jerusalem would look like in practice.

The journalist and academic Bernard Avishai, who first reported on the Olmert-Abbas meeting, describes Greenfield-Gilat and Bar-Sinai as “young and visionary.” In a blog posting about their work, Avishai wrote about “how vivid peace looked when you could actually see the constructions that would provide it a foundation.”.

The two architects have been honing their ideas since they met as students at Israel’s Technion University in the late 1990s. The Israeli government began building the controversial security barrier separating Israel from the West Bank in 2002, during their senior year, and talk of dividing Jerusalem was in the air.

Greenfield-Gilat and Bar-Sinai, joined by a close friend named Aya Shapira, began thinking about practical ways that the city could be partitioned without turning it into a modern version of Cold War Berlin. (Shapira was killed in the 2004 South Asian tsunami, and the name of their design studio, Saya, is short for “Studio Aya” in honor of their friend and colleague).

The three architects eventually settled on the idea of building parallel light rail systems in East and West Jerusalem that would come together outside the Damascus Gate of the Old City, turning it into a main transportation hub for the divided city. Their plan also called for turning the Damascus Gate rail station into a primary border crossing between the two states, making it, in Greenfield-Gilat’s words, a “separation barrier that was political but also highly functional.”

Part of their proposal was ahead of its time – Jerusalem has since built a light rail system with a stop outside of the Damascus Gate, something that wasn’t even under consideration in 2003 – but a peace deal dividing the city looks further apart than ever. There hasn’t been a successful Palestinian terror attack from the West Bank in more than a year, and Israelis feel little urgency about striking a deal with Abbas. The Palestinian leadership, for its part, distrusts Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and doesn’t believe he would be willing to make the territorial concessions they have demanded for decades as part of a comprehensive accord.

In the middle of a trendy duplex gallery near the Tel Aviv harbor, an exhibition showcases Greenfield-Gilat and Bar-Sinai’s plans and includes a vivid illustration of just how difficult it will be to actually bring about a deal. The architects installed a table-sized map of Israel and the occupied territories It is built like a puzzle, with visitors encouraged to experiment by picking up light-green pieces in the shapes and sizes of existing Jewish settlements and then comparing them to blue pieces corresponding to the swaths of land that would need to be given to a new state of Palestine in a peace agreement. (Greenfield-Gilat and Bar-Sinai have also developed an online interactive map that offers a similar experience.)

Two things become clear almost immediately. First, Israel would only need to annex a small amount of land to bring the vast bulk of settlers within the Jewish state’s new borders. Second, that annexation would still require the forced evacuations of dozens of settlements, including several with populations of close to 10,000. Some of the larger settlements are so far from Israel’s pre-1967 borders– and would require Israel to relinquish such an enormous amount of territory in exchange – that they can’t even be picked up off the puzzle board. Those towns house the most extreme settlers, so any real-life move to clear them out would hold the real potential for violence.

Greenfield-Gilat and Bar-Sinai are open about their belief that Israel will need to find a way of relinquishing broad swaths of the West Bank. Greenfield-Gilat spent a year studying in a religious school in the West Bank before entering college and describes himself as a proud Zionist. Still, he says that many settlements – including the Israeli community in Hebron, the ancient city that contains many of Judaism’s most holy sites – will need to be evacuated as part of any peace deal. “The deep West Bank won’t be part of Israel,” he says. “The map is meant to show what’s on the table, what is in the zone of the possible agreements between the two sides, and what the cost would be.”

In the meantime, he’s is trying to find other ways of putting Saya’s ideas into practice. Greenfield-Gilat has worked as an advisor to Tzipi Livni, now Netanyahu’s chief peace negotiator, and ran unsuccessfully for the Israeli parliament as part of her political party. He’s now running for a seat on Jerusalem’s city council. “Our mission is to prove that these are not issues that should be put aside because they’re intractable,” he says. “Dealing with them is just a matter of political will.”

This project was supported with a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Editor's note: This story originally mispelled Yehuda Greenfield-Gilat's name as Yehuda Greefield-Galit. We regret the error.