To understand the magic and mystery of Carrara marble, I was told to start with a ride up a mountain. So one crisp afternoon last spring, I donned a blue safety helmet and an orange vest and hopped into a Land Rover with Michael Bruni, a local guide.

The two-way, one-lane road was badly paved, and halfway up the mountain it became a rutted track littered with rocky debris. The incline was so steep and the switchback curves so sharp that Bruni had to stop the truck before we could turn. Beneath our wheels rocks shook and bounced the truck like a toy. Bruni explained that chunks of the mountain break off from the cliffs during heavy rainstorms or when mountain goats clamber up the slopes. He gesticulated dramatically as he told me about past disasters.

“Both hands on the wheel!” I said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/a2/99a2685c-5e37-457d-b1fc-0c4c793423f2/view_of_carrara_quarry_near_robotor_hq-1_copy.jpg)

Eventually we arrived at a flat lookout. Cut into the mountainside, off to our right, was a base installation for water tanks, trucks, forklifts and other heavy machinery. Workers wielding power saws cut blocks of stone ten feet deep from the sheer face of the mountain. There was no silence, only the shrieking of machines drilling into stone. It was only when I looked out toward the jagged peaks of the Apuan Alps and saw them frosted not with snow but with white, chalky marble that I could appreciate the vibrant beauty of this precious stone, which has defined this part of Italy for more than 2,000 years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bc/73/bc736c12-4500-422d-9221-6917493a592e/dec2023_a01_robotor.jpg)

In antiquity, Roman enslaved workers, free men and convicts removed marble from these mountains with wedges and picks to build Trajan’s Column and parts of the Pantheon. Great sculptors have been drawn to Carrara in the centuries since, from Bernini, Canova and Rodin to Jean Arp and Henry Moore. But nobody is more closely associated with Carrara than Michelangelo, perhaps the greatest sculptor ever to live. In 1497, when he was only 22, he came looking for the ideal pale stone for La Pietà, the first of his Renaissance marble masterpieces, now installed at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Bruni explained that Michelangelo spent long stretches in these hills in search of perfect blocks of marble, especially the bright white “statuario,” a type of pure stone nearly devoid of silica that best captures the vitality and sheen of the human form.

Michelangelo cultivated relationships with excavators, cutters and carvers so that they would favor him with their best blocks, and he offered precise instructions about the shape and size of the marble he desired. Then, satisfied, he would hammer and chisel until the figure revealed itself. His ghost still hovers above the quarries here. You can hear the famous words attributed to the Italian master: “Every block of stone has a statue inside it, and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.”

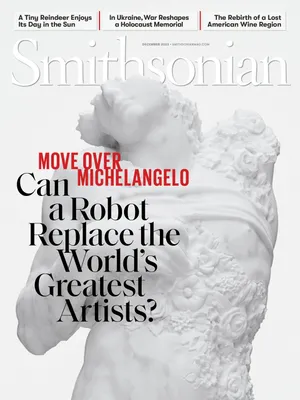

The British-born, New York-based photographer Caleb Stein has long been fascinated with that moment of discovery, which he identifies as “the point where the suggestion of a shape of a figure begins to emerge from what is still a discernible block of marble.” Earlier this year, Stein learned that an industrial area outside Carrara was home to a group of up-and-coming marble sculptors—powerful, automated robots belonging to a company called Litix (formerly Robotor). Stein, whose photographs often highlight the sculptural nature of the human body, traveled to Carrara to document the process of a single sculpture’s creation by a robot from beginning to end, the subject of these accompanying photographs. “I was interested in making intimate ‘portraits’ of the robots at work,” he said. “I wanted to extend tenderness and sensuality to the process, just as I would when photographing a person.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6c/53/6c53204b-0f48-4545-ba31-4231c63fa8c5/carrara_marble_stored_near_robotors_hq_view_1_of_2-1_copy.jpg)

Litix is the brainchild of Filippo Tincolini, a sculptor who was educated in Carrara, and Giacomo Massari, a local entrepreneur, both in their 40s. For decades, Carrara sculptors had been using small machines like electric grinders, diamond-beaded band saws and pneumatic chisels. Tincolini saw an opportunity to take the process further. “My father made electrical parts for assembly lines, and though I didn’t want to go into his business, I learned from him,” he said. The younger Tincolini bought an automobile assembly line robot and put it to work on stone. “I didn’t know how to use it, but little by little, and with a lot of marble dust, I figured out how it worked and how to improve it.”

Today, Tincolini, Massari, and their team of technicians and artisans create sculptures on commission for artists, architects and designers, and they sell their technology to clients around the world, including three sizes of Litix’s signature robot and a proprietary software that uses a digital scan of an artist’s 3D model or maquette to auto-program the robot for sculpting. They also use their technology for cultural preservation. A few years ago, for example, in collaboration with the Institute for Digital Archaeology, a heritage-preservation organization based in Oxford, England, their robot produced a one-third scale model of Syria’s Palmyra Arch, the 1,800-year-old monument destroyed by Islamic State fighters in 2015. The copy, a 20-foot-high scale reproduction made of Egyptian marble, took five weeks to manufacture. It toured several cities around the world, including London and Washington, D.C., and is now undergoing cleaning and maintenance in Carrara. The hope is that its final destination will be near the site of the original in Palmyra. “The message was, ‘You can destroy it, but we have the technology to make it live again,’” Tincolini told me.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ba/8a/ba8a134b-01f6-4d50-9a07-0749b3473064/untouched_marble_bloc_before_the_robot_carving_process_begins-1_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a8/a0/a8a0c542-bcc5-4a01-b1da-f78ceb1c0a01/further_into_the_production_with_view_of_carrara_mountain_behind_the_working_station_view_1_of_6_new.jpg)

On a tour of the area, I passed through a warehouse and traditional workshop with shelves stuffed with marble funerary sculptures and crucifixes; lining the edges of the floor were decades-old hand-carved works alongside robot-created pieces such as a gigantic sculpture, carved from black marble, of a baby wearing a blindfold.

Massari has his best lines down pat. “What used to take months or even years can now be done in days,” he said. “Machines can run round-the-clock. They don’t get sick or sleep or go on vacation.” One of his favorite stories is about Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, Antonio Canova’s 1793 neoclassical masterpiece that sits in the Louvre. “It took Canova five years,” Massari said. To make a replica “took our machine 270 hours”—less than 12 days.

When I asked Massari whether he thought Michelangelo, who like other great sculptors then and now relied on apprentices to create his masterpieces, would have used robot technology had it been available to him, Massari seemed to bridle. “Of course he would use robots—100 percent! I tell people who question what we do: How did you come here, on foot, on a horse or in a car? The car cuts time off your journey. So does a robot. An algorithm does what a caliper used to do. I have the time to contemplate a beautiful sunset because a machine does all the hard stuff.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4e/86/4e8606ac-511d-476b-9e1c-a48dc76f76a4/beginning_stages_of_production_of_artist_filippo_tincolini_sculpture_at_robotor_view_6_of_7-1_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/31/8d31555b-05cd-41f9-a8da-44fbbaf755ed/further_into_the_production_of_artist_filippo_tincolini_sculpture_at_robotor_view_6_of_6-1_copy.jpg)

Already, Litix has made sculptures for artists including the late Iraqi British architect Zaha Hadid, the American Jeff Koons and Giuseppe Penone, a luminary of Italy’s Arte Povera movement. Massari opened the door to a cavernous carving studio. “We’re working on a masterpiece—something crazy, big, huge,” he said. “A very special piece. The selection of the block was crazy, because finding a pure white block is very hard. It’s a famous sculptor. But we don’t want to talk too much.”

Inside, Robotor One, the company’s star robot, an 11-foot-long, zinc-alloy anthropomorphic arm, was busy at work, milling the block by moving methodically back and forth. The arm’s diamond-studded “finger” was spinning so fast that I couldn’t see it moving, and water sprayed out from the arm, cooling the tip, which was fashioning the intricate lacework of a woman’s voluminous skirt from the stone. “The final sculpture will be about four tons,” Massari went on. “The machine time is going to be 18 months.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/3a/b63aafac-d8c8-414f-847b-6084abc24da4/view_of_interior_of_carrara_quarry_with_quarry_equipment_view_2_of_3-1_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3f/f6/3ff6100c-4bd4-4783-8ddc-2a5d15101f52/right_triptych.jpg)

At that point, the final details will be executed by human sculptors—even Litix’s techno-evangelist owners don’t pretend that its machines can match the finest subtleties of human artisanship. In an adjoining studio, I found a group of such artisans, streaked and frosted with marble powder, putting the finishing touches on several sculptures commissioned by a well-known British artist who wished to remain anonymous.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5a/a7/5aa7e0d4-27c2-4e4f-8e5d-4e2ed5c05a17/beginning_stages_of_production_of_artist_filippo_tincolini_sculpture_at_robotor_view_3_of_7_-1_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/72/4d/724d9ccd-fbf9-45b6-bb46-ef44c15b3f73/final_stages_done_by_human_hand_of_artist_filippo_tincolini_sculpture_at_torart_view_3_of_3-1_copy.jpg)

“I come from the old tradition, when everything was done by hand,” said Romina del Sarto, 53, who was working with a small hand tool. Her shoes, and even her braid, were caked with marble dust. Del Sarto began working in her father’s sculpting workshop when she was 17. “Everyone lives off marble here, and I’m grateful for the job,” she said. “But sometimes Carrara feels as if it’s losing a part of its history.”

I found a living link with that fading past in the nearby town of Pietrasanta, when one afternoon I visited Enzo Pasquini, who has worked only with hand tools since his days as an apprentice more than 70 years ago. He is now 83. Around town he’s known as a master who can carve the most elaborate details into stone.

His home is set in a small farm of olive and cherry trees, a vineyard, a fruit orchard, and vegetable and rose gardens. Taped to the wall of his studio was a yellowed photo of Michelangelo’s Pietà that, he told me, has inspired him for much of his professional life. “I always worked from beginning to end, from the huge block of marble to the delicate sculpture,” he said. “Chiseling the block—it’s a heavy, heavy job. I was strong when I was young and didn’t mind it.”

His tools include hammers, chisels, saws, rasps, files and curved steel calipers in several sizes. There are also tools he made himself, such as a hand drill called “the violin” that needs two people to make it work; one person holds the handle of the pointed drill, while the other pulls on a string that drives the point into the stone. “We used this in the days when there was no electric drill!”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2f/09/2f096245-e1c2-4582-b392-348dd0919c26/robotor_portrait_4-1_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ae/9e/ae9e16cd-d7ac-4d28-a509-9e51ec4a2fd2/close-up_view_of_the_robot_marks_which_remeble_topographical_map_lines_that_are_later_refined_by_human_hand_view_2_of_2-1_copy.jpg)

Pasquini has used his skills mainly to help other people produce their sculptures in marble; among his carving partners was film star Gina Lollobrigida, who went on to become a respected sculptor and photographer after her film career and who died in January 2023. “I am not an artist,” Pasquini said. “I’m just an artisan.” But he has made his own sculptures, many of which he keeps in his house and studio—a small, refined figurine of a boy fishing; a baby with tiny, delicate fingers; a pack of playing cards.

He picked up another tool made of two pieces of wood and a vise held in place with glued-in nails. “This is my robot,” he said. “If I want to do something that’s good—that’s mine—I have to do it the old way. But you have to go with the times. There are fewer and fewer young people who want to do hard physical labor. But machines won’t change the sensitivity of the work. You will always need the sculptor for that.”

:focal(1200x903:1201x904)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/68/01/6801b243-4116-4594-b197-3eafe4252dac/three.jpg)