Can Social Media Give Sharks a Better Reputation?

A nonprofit called Ocearch is naming tagged sharks and giving them Twitter and Instagram accounts to ease fears and aid in conservation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/62/ae62132c-8b42-449a-b680-126075ba9004/surfers-in-montauk.jpg)

The pup lays on her stomach as a scientist looks down from above, contemplative. Researchers have been scurrying against the clock to conduct tests on her, and now a radio transmitter is clamped securely to her back. Exhausted, two thick tubes protrude from her open mouth, lined with rows of razor-sharp teeth. In the distance, a fuchsia sunset dips into the Atlantic.

“Aww,” someone says later. “So cute seeing a baby white.”

It’s exactly the response researchers here are hoping to get. The patient—a 4-foot-6, 50 pound great white shark pup—was hauled out of the waters of Montauk, New York by researchers who discovered a nursery offshore last summer. The photo, posted on Instagram, got a few thousand shares on social media, getting the kind of warmth you don’t normally see people express about sharks. “So cute, so small!” one person observed. “Can I have one as a baby?”

Now, scientists are hoping to use new means to solve an old problem: great white sharks, it’s time for your social media re-brand.

Anyone who’s tuned into “Shark Week” can attest that the ocean’s top predator has an image problem. But can Tweets and Instagrams really change our psyche?

For researchers at Ocearch, the answer is yes. For the past decade, Chris Fischer, the nonprofit research organization’s founder, has tracked great white sharks from Australia to Nantucket.

The pup, named “Montauk,” is just one of 188 sharks Ocearch tracks worldwide in an effort to promote understanding and conservation of the endangered predator. Scientists aboard Ocearch’s research vessel tag sharks with devices that transmit information to a satellite.

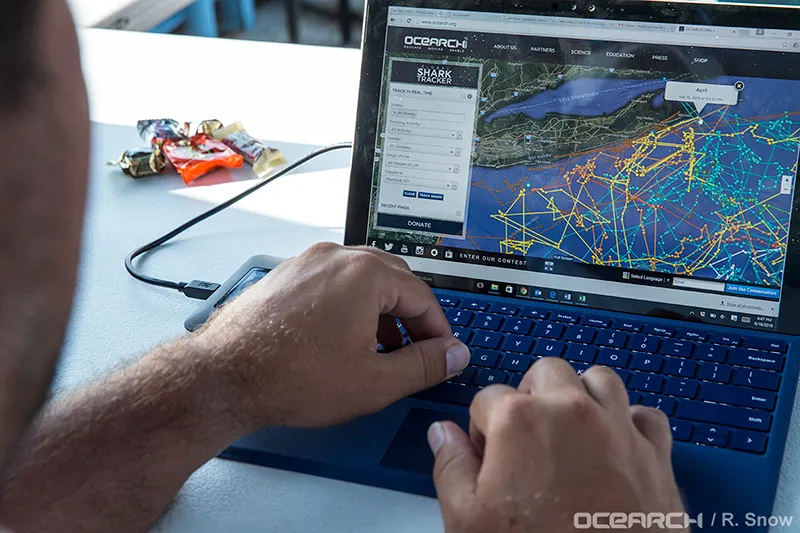

The tags give researchers information about their movement and behavior never before thought possible, and the scientists use the data to learn where sharks go, where they breed, and what they do. But they’re not the only ones who can enjoy it: Using an app, anyone can follow the sharks on their smartphone.

For Fischer, it’s as much about research as overcoming stereotypes.

“We're replacing the fear of the unknown with facts and fascination,” Fischer says.

There’s a 1 in 3,700,000 chance of dying from a shark attack, lower than the chance of getting struck by lightning. Despite the odds, few animals inspire terror like sharks. Galeophobia (fear of sharks) stems from what psychiatrists describe as our evolutionary reaction to the unknown because of our perceived defenselessness bobbing on the open ocean. Moreover, the results are gruesome: lost limbs, evisceration, disfiguring bites. Sharks are, in the words of an Australian social anthropologist, “Symbolic of nature in its most aggressive and destructive form.”

This past fall the Ocearch crew docked in New York City for a few days to give the team a rest and give tours to the public. It had been a busy summer. They’d just come from an expedition off Cape Cod, and weeks before they’d created a buzz after they announced the discovery of a great white shark nursery off the coast of Long Island.

The nonprofit has brought more positive attention to the fish. In addition to Ocearch’s 67,000 Twitter followers and 93,000 Instagram followers, popular sharks like Mary Lee and Lydia have their own Twitter accounts. Users of Ocearch’s app can follow tagged sharks up and down the East Coast thanks to a tracker that pings their location in real time to a satellite.

“Now you can track the sharks, the media is tracking the sharks, and every time a shark passes through their town, there are hundreds and hundreds and thousands of stories in play about what this shark is doing here, [like] ‘Maybe that shark's pregnant!’ Or 'She's giving birth!’”

“The only time there was a story about a shark was when there was an attack. There were no stories, no stories, no stories, [then] shark attack,” Fischer says.

For many, that change in narrative is already having an effect. James Stanton, 41, of Connecticut brought his son to see the Ocearch boat docked in Brooklyn. “It used to be if you saw a seal it was cute. Now you just get out of the water,” Stanton says.

“We always knew that sharks were out there. But never how close. Now there’s data, which helps us understand how sharks feed and behave. And more information is less scary.”

Marianne Long, who teaches at the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy in Cape Cod, always asks the same question first: What does the word shark remind you of?

“Automatically, that first answer is ‘Jaws.’ And I ask, ‘What kind of shark was Jaws’ and people will say, ‘a villain.’”

It’s a narrative Long hopes to dismantle. But explaining the slim chances of being attacked, or the importance of sharks in the oceans ecosystem, didn’t resonate as much as a trick every child knows: giving each shark a name.

Tagged sharks are typically assigned numbers, which serve as their identification. Now, the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy monitors sharks named Tom Brady and Big Papi, bringing widespread media coverage.

Not everyone is convinced social media can help. Chris Neff, a public-policy shark expert who teaches at the University of Sydney, says naming animals helps humanize them, diminishing our hard-wired anxiety. But the idea of sharks turning over another leaf remains a long-term project.

“The word shark is scarier than actually seeing a shark,” Neff says. "The only people I think were positive about sharks were that way to begin with. People who were skeptical about sharks and then see it thrashing about on the deck of a boat or a trolley are still not likely to be supportive of sharks.”

Neff, whose research into government responses to shark bites advocates for new language to describe human-shark incidents (sightings, encounters, bites and fatal bites), found that the media hysteria around an incident is more of a concern than the event itself.

“I don't think people finding out that there are sharks in Montauk and their local community is going to lower concerns,” he says.

While social media is most often linked to the fear of missing out, social researchers have documented how it can spread unfounded fears of terrorism and, in 2014, Ebola. The problem is that misinformation can disseminates on social media faster, and farther, than facts. Neff says the effect is evident with sharks, too. He pointed to a moment in 2015 when surfer Mick Fanning’s close encounter with a great white shark was taped. Media outlets reported Fanning was attacked by the shark, despite it swimming away and Fanning not actually being bitten. But the video went viral, and the incident labeled a shark attack to the anger of experts like Neff.

“It's the most famous shark attack that wasn't a shark attack,” Neff says.

It’s a problem George Burgess, the director of the International Shark Attack File, has wrestled with for decades. Burgess, who oversees the collection of shark encounters going back to the 1500s, says sharks are unlikely to get a makeover because scientists, even when they can agree on the facts, never craft a singular message. Staff at the Florida Natural History Museum, where he works, scan social media postings for shark incidents so they can categorize the event and get the real facts out there. “Humans will always be interested in sharks because they’re one of the few animals on Earth that can kill and eat [them].”

When researchers discovered the rare great white shark nursery off the coast of Montauk—the infamous home of Hollywood’s Jaws—not everyone celebrated. For Corey Senese, who runs a surfing school there, it meant an unnecessary reminder of the dangers faced every time he stepped in the water.

It’s not that Senese feared getting bit: in almost four decades of surfing, he’s never had a close encounter. But now his friends were sending him Facebook posts showing that sharks were located just off the waters. Now, it was getting harder to forget that they were out there.

“But by the time you get it [a friend’s Facebook post], the shark was pinged last month,” Senese says.

Ocearch’s system is limited in that it tracks the sharks only when their fins break the water, not as they move beneath the waves. So between pings app users do not know a shark’s whereabouts.

“Why can’t they know where it is at all times? If we know it’s right outside our surf break, we just won’t surf that day,” says Senese.

“You find yourself thinking about it,” he says. “It would be interesting to know when you, as a surfer get a feeling…was there actually a shark close to you?”