Can Underwater Resorts Actually Help Coral Reef Ecosystems?

A Los Angeles company is designing artificial reefs to boost local economies and marine habitat

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/d7/1ad76520-10ca-4939-8ba2-2f9ddad1f6ac/pearl_of_dubai_lost_temple_uw.jpg)

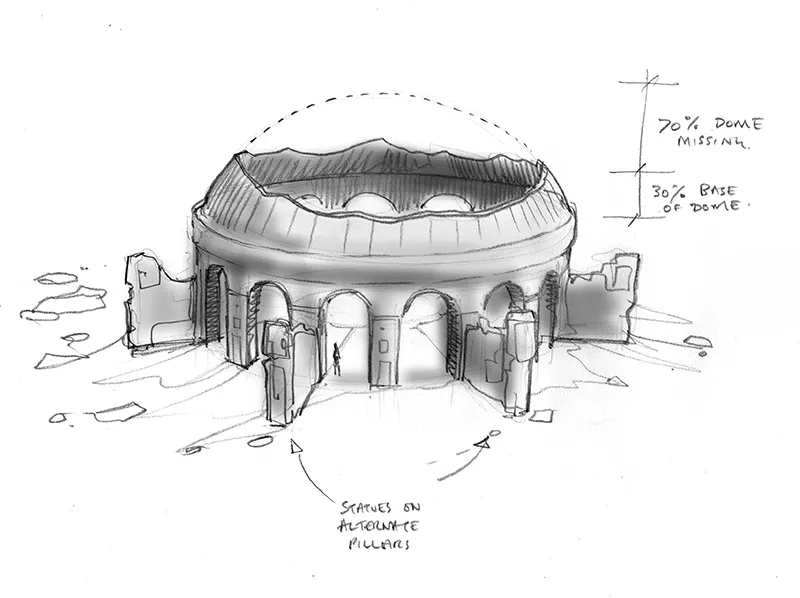

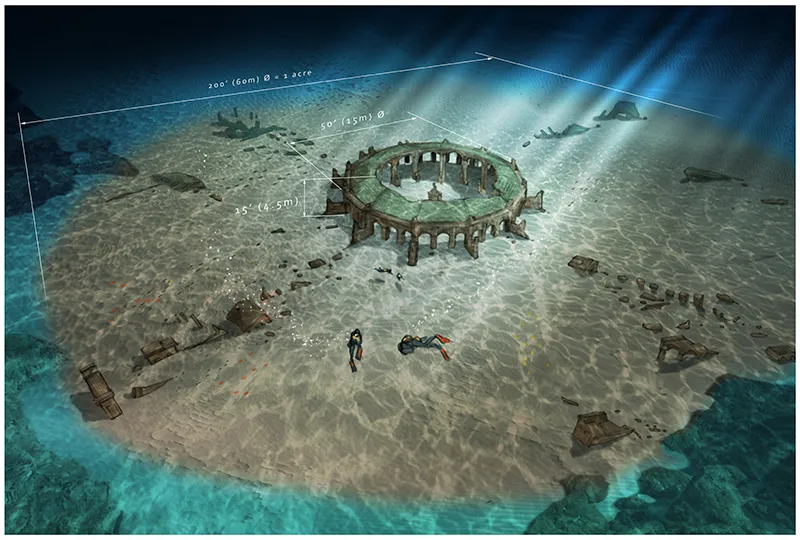

Dubai, known for such modest ventures as the Burj Khalifa and the artificial Palm Jumeirah islands, is on the verge of building yet another one: the fabricated ruins of an “ancient” pearl-trading city, submerged just off its shores in the waters of the Persian Gulf.

Half adventure park, half marine sanctuary, the Pearl of Dubai will be the first-of-its-kind artificial reef, built to attract diving dollars from tourists, but also to encourage the return of once-abundant species whose populations are flagging.

Reef Worlds, a Los Angeles-based company, is at the helm of the Pearl project, as well as two other developments in the planning and design stage in Mexico and the Philippines. Company founder Patric Douglas says the idea grew organically out of his previous work with Shark Diver, the excursion company he founded not only to popularize shark diving, but also to educate divers on the plight of sharks in oceans worldwide. He hopes to do the same thing for decimated coral reefs.

In the immortal words of Kevin Costner, build it and they will come. Though artificial reefs have been used for centuries as defensive structures, breakwaters and to attract fish, the typical reason modern reefs are built is to increase available habitat for coral and fish. Divers come as a consequence, but the reefs weren’t built for them.

Artist Jason deCaires Taylor creates underwater installations with sculptures made from highly detailed casts of real people. He recently completed a project in Lanzarote, Spain, and his installation in Cancun, Mexico attracts thousands of divers every year. As part of its statewide initiative to increase reef real estate off its shores, Florida sank an entire aircraft carrier, the USS Oriskany. And the half-acre Neptune Memorial Reef site in the waters off Miami, inspired by the lost city of Atlantis, is designed to eventually accommodate the cremated remains of people interested in a different kind of burial at sea.

Reef Worlds’ take on artificial reefs adds a new paradigm: their installations are designed first for customers with credit cards, and then for ones with real fins. Primarily intended to provide tourists with a new adventure-based experience, and in places where they are already present in great numbers, Douglas hopes the increased traffic will create a positive feedback loop. By making reef ecosystems more accessible to more people, a large part of the goal is to drive a greater demand for conservation of those natural resources.

Diving is big business, and coral reefs a big part of it. A 2013 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) report pegs the economic value of all coral reefs in the United States and its territories at $202 million dollars annually, with half of that figure accounted for by tourism dollars. Douglas thinks this kind of buying muscle can be built up around the world, creating not only a novel and authentic adventure experience but also a powerful tool for restoring critical ocean habitat.

Gone are the days when a visitor to a Caribbean resort can walk out on a near-shore snorkeling tour and see coral reefs teeming with life. Today, that excursion usually involves a lengthy boat ride. But hotels at tropical resorts are still trying to one-up each other in the battle royale for tourism dollars: the swimming-pool wars of the 1980s and 1990s gave way to full-blown water parks like Bermuda’s Atlantis, yet the resorts themselves seemed to completely ignore their offshore assets, Douglas observed.

“My team and I were lamenting that at every hotel resort we went to in the Mediterranean and Mexico, the near-shore reef system was just gone, like a nuke went off,” Douglas says. “So the question became, what can we do to rehabilitate that, and what’s the tourism angle? All of these resorts are 200 feet from the ocean, but have nothing to do with the ocean.”

Douglas, a self-described “environmentalist masquerading as a developer,” says coastal resort hotels are uniquely positioned to grow their business by developing recreational opportunities in the water, but also to defend the natural resources there. By motivating local residents to help protect the reefs, they can help tourism grow and increase incomes for everyone involved.

“This is a major question: how do you stop the local fishermen from making a living?” Douglas says. “You can’t pay them not to fish, especially when they’re dirt poor and they need to go out and scavenge whatever they can get. But I’ve been to enough of these hotels to know that most of the people in the community are working there, and when you explain to them what the reef [can do for tourism], they’ll tell their family, don’t fish there. It’s not good for us or the community.”

The network Douglas imagines is grand: at each of the first three planned properties, the reef territory will cover a five-acre plot with a mixture of open ocean floor and full-sized structures for exploration. Buildings will be constructed in a way to maximize fish and coral habitat; for the “Gods of the Maya” project in Mexico, full-scale replicas of Mayan stelae and other sculpture will not only showcase the country’s cultural heritage, but also provide plenty of nooks and crannies for critters.

To build these underwater resorts, Reef Worlds translates computer-based designs into full-scale, hand-finished foam blocks, which are then used to cast the molds for the final structures. Once on site, the molds are filled with a mixture of coral and basalt rock substrate, cured and submerged.

In Dubai, Douglas says the client initially wasn’t as concerned with the ecosystem restoration component as they were about simply having something to boost diving tourism in the country. But after being convinced that supporting the return of the brown spotted reef cod, a delicacy known locally as hamour, would also encourage divers to come swim with the popular fish, they asked Douglas to “Swiss cheese” the designs of the underwater city to give baby cod a place to hide and thrive. Reef Worlds is planning the release of two million baby hamour into the Dubai reef as part of the project.

Yet while revenue is the reason for the projects, it relies upon public passion to create the demand to protect them in the long term, Douglas says.

“Once people have a more authentic experience, and engage with a reef on a fundamental level, it changes their whole focus and attitude,” Douglas says. “It’s cool to say that you went underwater and saw fish, but it’s important to learn why it’s there, and that it’s a replacement for what was once there. You’re now in participation to make it right, and make it better—even though it doesn’t make up for what was once there.”

Keith Mille is a fisheries biologist who has worked in the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s artificial reef section for 14 years, overseeing the planning and construction of reef projects in the state. As public properties, Florida’s reefs are open for recreational fishing and diving, but are also used in research. Mille explains that man-made reefs often work best as a diversion to take pressure off of natural reefs.

“That is a trend, statue-type deployments that are more focused on attracting people than fish,” he says. “But there’s a dichotomy there. If you’re improving fishing opportunities, sometimes the outcome of that is reduced biomass and increased fishing pressure. But on the other hand, by directing fishers and divers to an artificial reef site, you could potentially reduce traffic to more sensitive areas for an overall net benefit.”

But Mille notes that artificial reefs aren’t an adequate substitute for appropriate fisheries regulations for the protection of sensitive marine habitat.

Douglas, whose Shark Divers company created the Shark-Free/Shark Friendly Marinas Initiative, argues that prior to charging people to go dive with sharks, the idea of shark protection areas in the Pacific equivalent to the Australian continent was unimaginable.

“Unfortunately, there’s a very strong abhorrence for anything that’s for-profit,” Douglas says. “Who would have thought that in 2003 when we were yelling about sharks being killed that we’d have so much shark sanctuary today? But people who had been diving, who came home and put their pictures on the Internet and opened the minds of a thousand of their friends, drove all of it. To save a thing, you have to put money into it, and the best way to do that is charge people to go see it.”

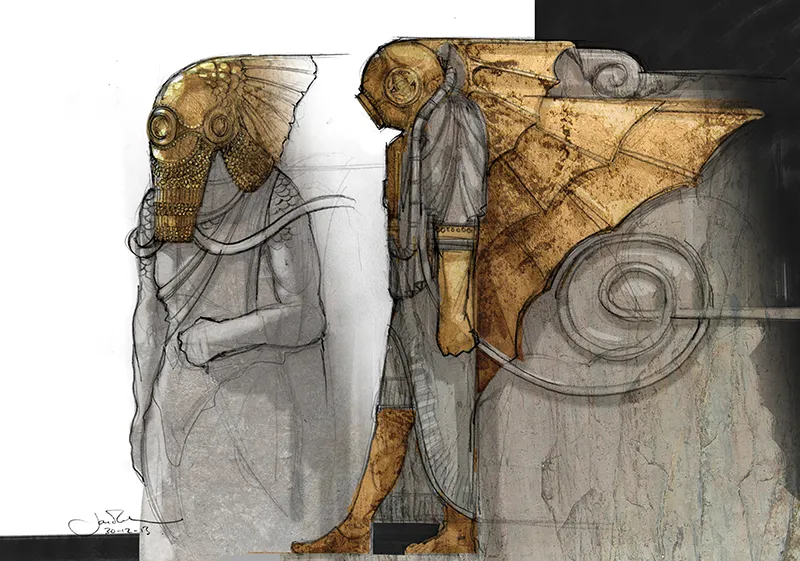

Estimated to cost around $6 million to build, the Pearl of Dubai project will include numerous “ruins” of buildings, dive-helmeted statues, avenues and trading markets to explore, including a large semi-enclosed coliseum that could be used for underwater meetings or weddings. Douglas says he expects construction to begin later this year.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)