A Century Ago, This Eerie-Sounding Instrument Ushered in Electronic Music

Now, the theremin—a strange little invention that translates hand gestures into pitch and volume—could make a comeback

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/88/71/88716b45-b765-4f3e-9b4e-616e3f836628/dorit_chrysler_photo_by_udosiegfriedt.jpg)

The “Play It Loud” exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art spotlights the star instruments that made music electronic, from Muddy Waters' blues axe to a shard of the psychedelic guitar that Jimi Hendrix set aflame at Monterey. Keith Emerson's Mellotron keyboard still has a knife driven into its keys.

Tucked in the back is a small boxy item that doesn’t look like an instrument at all, but it was the one that came first. The theremin is the granddaddy that kicked off the past century of electronic music. Invented by Russian musician and scientist Lev Theremin, it bears his name.

The theremin has no strings or even moving parts. It doesn’t rely on a player’s breath. But it translates her hand gestures and motion in the air into pitch and volume, using the principle of heterodyning. In the rock era, the theremin’s unique and often eerie sounds excited legends including Brian Wilson and Jimmy Page. It was one of the good vibes in the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” and was featured in some of Page’s out-there solos with Led Zeppelin.

“It was the first successful electronic instrument,” says Jayson Dobney, a musical instruments curator at the museum. The theremin in the exhibit, a Sonic Wave built in New York, belongs to Jimmy Page, who played it in “Dazed and Confused” and “Whole Lotta Love.” According to Dobney, Page “got so excited, he demonstrated it,” when the Met asked to display the instrument.

“Lev Theremin influences everybody including Moog,” adds Dobney. Robert Moog, that is, the electronic music pioneer. As a 14-year-old, Moog built his own theremin from drawings he found in a hobbyist magazine.

“Theremin has touched the lives of countless musicians and scientists,” Moog wrote in a foreword to Theremin’s biography, “and his work is a vital cornerstone of our contemporary music technology.”

On the cusp of its centennial, the weird boxy instrument is enjoying another revival. Hollywood paid tribute in First Man, where the theremin plays a central role in the score (Neil Armstrong was a fan of the instrument).

In the Beginning Was the Sound

Dorit Chrysler first encountered the theremin in New York in the 1980s. A native of Austria, Chrysler had absorbed classical music training and then rebelled against it by founding a punk band. She was visiting an artist friend in New York. “He pointed me towards his living room, where this unassuming wooden box stood in a corner,” she says. When he started playing it, “suddenly this odd, unique sound that I've never heard before seemed to come out from this box and responded to however he moved his hands, waving in the air.”

“I call it now the Houdini effect,” she says of seeing the theremin played for the first time. “Because it seems to defy the laws of physics.” Chrysler was inspired to take up the theremin, both as a performer with leading classical orchestras and as a composer.

Like so many inventions, it was an accident. Theremin was a radio engineer with the Soviet military in 1918 when, while building a powerful transmitter-receiver, he noticed odd feedback sounds coming from it. He said in a 1995 interview, “it turned out that when the capacity changes at a distance of the moving hand, the pitch of the sound also changes.”

He had happened on heterodyning, a process that combines two frequencies to shift one frequency range into another, new frequency. It makes for a change in pitch and volume.

Other radio engineers in Europe at the close of World War I had noticed the same effect but Theremin was the first to play with that feedback or heterodyning effect in a musical way. The new sound pleased the inventor. Fully committed to Soviet nationalism, Dobney says, Theremin “tried to find a musical sound that was modern, forward looking.”

In 1919, he built a prototype of what would become the theremin. The instrument made its first public appearance in 1920.

Theremin brought his invention to the U.S. in December 1927 for an extended tour. While he pursued a U.S. patent, he performed with the New York Philharmonic and at Carnegie Hall. The New York Sun reported that the audience at Theremin’s debut at the Metropolitan Opera was “pleased, entertained and a bit awed.” When they went on sale at $175 each (over $2,600 in 2019 dollars), the instrument became a luxury purchase for Jazz Age moguls, and Henry Ford’s son is said to have owned one.

The inventor considered it revolutionary. “I'm always quoting what Lev Theremin said in an interview in the New York Times,” says Chrysler. “And the literal translation is, “My apparatus frees the composer of the despotism of the 12-tone scale and offers infinite new tonal possibilities.”

Theremin’s tour of Europe and America was sponsored by the Soviet government to show off Soviet technology to the world. Like any musician with a tour sponsor, says Chrysler, he reported back with updates.

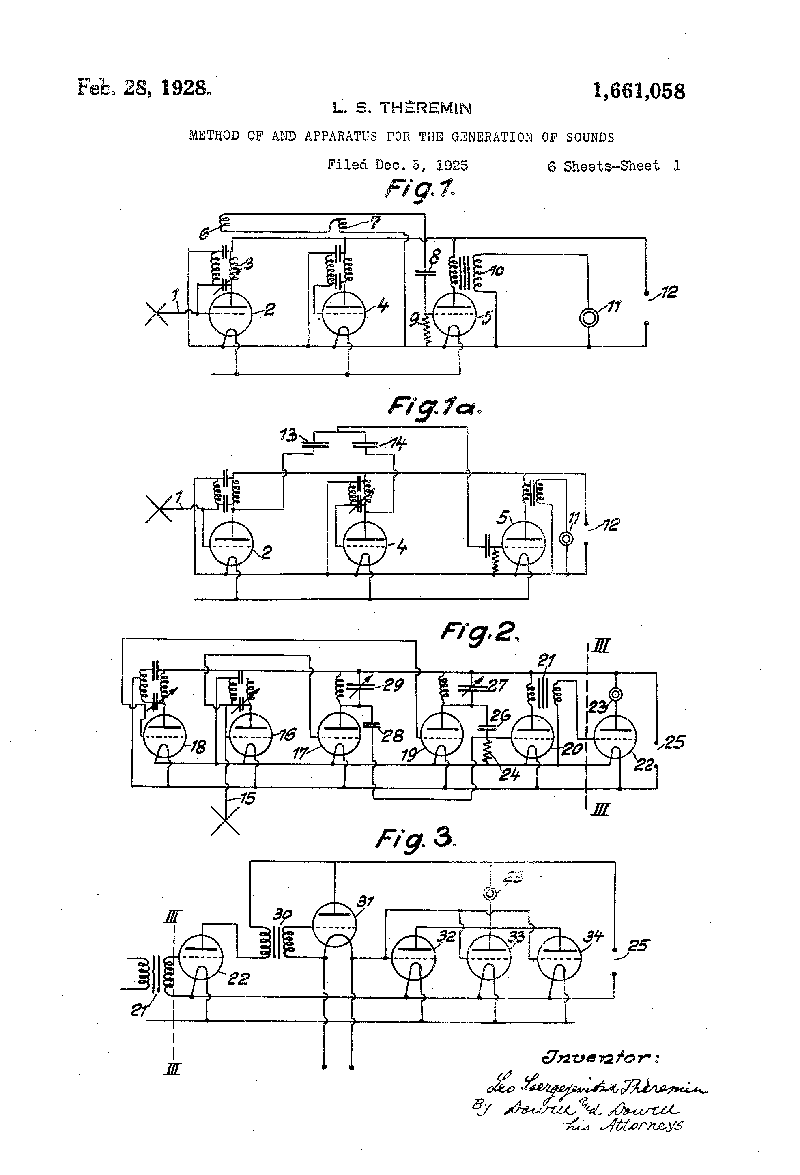

“And that's why the theory emerged of him being a Russian spy in America,” she says. More likely, he was simply keeping his tour sponsor happy, showing he was busy. Theremin received his patent in February 1928. His invention, he wrote in the application, “aims to provide a novel method of and means for producing sounds in musical tones or notes of variable pitch, volume and timbre in realistic imitation of the human voice and various known musical instruments,” using “an electrical vibrating system.”

The inventor liked America and stayed, collaborating with musicians and promoting his invention. But when the Depression hit, nobody could afford the instruments. Then Theremin ran into tax trouble and fled back to the Soviet Union in 1938. Without him, his invention languished until the 1950s, when a new generation found its eerie, futuristic sound perfect for sci-fi soundtracks.

Waves of Influence

Almost forgotten by then was the vocal range the instrument had shown in early concerts. Chrysler, who likens the theremin to the human voice, still yearns to hear it the way its first audiences heard it when the singer Paul Robeson went on tour in 1940 with the new instrument.

When she learned to play the theremin, what struck Chrysler most was its emotional expressiveness. “The slightest motion of your body affects the sound,” she says. “It really transmits any kind of emotional state just as the voice does—if your voice is trembling, if you're anxious, if you’re angry, or happy. They're different colors.”

The theremin influenced the creation and evolution of many other instruments, picking up in the 1960s from Moog synthesizers and MIDI to, indirectly, wailing guitars. In the flood, the theremin itself got a little lost. “It fits in everywhere and nowhere, ”Chrysler says. “It is incredibly versatile. I can find myself one moment being the soloist with the San Francisco Symphony and having some older violinists ogling the instrument with suspicion and not being really very happy, with other sections of the orchestra really excited about it.”

Or she can then find herself at the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland, performing before scientists. “You suddenly collaborate with CERN and nuclear physicists who work with electromagnetic fields, because it ties into such a beautiful, literal explanation of this very simple physical phenomena,” she says. Watch Chrysler perform “avalanche” there in 2012:

The theremin’s emotional range comes across in recent films including Alex Gibney’s 2015 documentary Going Clear, for which Chrysler infused a classical lyricism in a song heard over the death of L. Ron Hubbard. She also used the theremin in scoring an Austrian mini-series, a remake of Fritz Lang’s classic film, M.

Revolution Coming?

For its centennial, the theremin is enjoying a resurgence of interest. The New York Theremin Society, which has grown in membership since Chrysler co-founded it in 2005, put on a big theremin concert last December and is organizing more events for the coming year, perhaps one where several early theremin models from private collections get played together.

In those early models, Chrysler hears the sound of a bigger promise, a revolution in music. "It's literally something on the sonic spectrum that no one has heard before,” she says. “By comparison, [the theremin] we have today is like a little tricycle."

This fall, the Dutch group Amsterdam Dance Event is putting on a festival with performances that celebrate the theremin and its influence. ADE reminds us "the story of electronic sound is of people, scenes and societies every bit as much as it is of wires and circuits." It's a celebration, in the organizers’ words, "of the wild, sometimes cracked, minds that have created or popularized the devices that in turn expanded our collective imaginations.”

Theremin’s 1928 patent was not renewed, so while other versions are protected, the basic theremin design is in the public domain. A curious teenager like Moog can still make one of his own.

"Play It Loud" is open at The Met Fifth Avenue through October 1, 2019.