Cities Around the Globe Are Eagerly Importing a Dutch Speciality—Flood Prevention

Architects and planners from the Netherlands are advising coastal cities worldwide on how to live with water

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/6e/a66e7d29-6341-4857-8586-32bef788e2d1/storm_surge_barrier_in_netherlands.jpg)

Norfolk, Virginia, was founded on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay in the 17th century, but when the city needed new ideas to deal with sinking land and rising seas it turned to people with even more experience fighting flooding: the Dutch.

Like the Netherlands, portions of Norfolk have arisen on wetlands and even creeks buried beneath fill. And similar to the Netherlands, where two-thirds of the country is vulnerable to flooding, Norfolk is threatened by rising tides and intensified storms.

So the city imported expertise, staging the Dutch Dialogues, a traveling roadshow that is a cross between a seminar on local hydrology and a design charrette. The dialogues, initiated by Waggonner & Ball Architects, a New Orleans firm, and the Royal Dutch Embassy, are just one example of how a world increasingly imperiled by water is turning for guidance to a country where there is no retreat from rising seas.

"It's self-evident that the Dutch have developed an expertise in water and water management that is unparalleled in the world and this was an opportunity for us to learn from them," says George Homewood, Norfolk's director of City Planning. "The first Dutch Dialogue was done in New Orleans right after Katrina and became a model in the planning world for how we think about our watery future going forward."

For the Dutch, consulting with cities about their response to relative sea-level rise has become a growth industry. They're the Silicon Valley of water management, a laboratory testing strategies that have evolved over the centuries. No wonder. Water has been both a daily threat and a national identity for a country about the size of Maryland. More than half the nation's 17 million people live on land below sea level. The Netherlands takes exporting water knowledge so seriously that it has a Special Envoy for International Water Affairs, Henk Ovink, who travels the globe on behalf of Dutch experts.

"The Netherlands has a long history of water management because half of the country is based below sea level," says Lisette Heuer, global director of flood resilience for Royal HaskoningDHV, a firm with projects on five continents that participated in the New Orleans dialogues. "From prehistoric times people have learned to live with water and in medieval times founded authorities tasked with water management and flood defense."

The Dutch have learned there are no easy solutions. As David Waggonner, the founder of Waggonner & Ball says, "They made a lot of mistakes, and they learned from those mistakes."

Their thinking about living with water has evolved in recent decades. In 1953, a storm flooded the country, killing more than 1,800 people and damaging 47,000 homes. The Dutch call it the “Disaster.” That led to a massive building boom, the Delta Works, which created barriers, dams, dikes, levees and two of the world's largest storm surge barriers at a cost of $5 billion.

But over time—and after a series of floods in 1993 and 1995—the Dutch realized raising a fortress against the inevitable invasion of water wasn't a solution. So they moved on to focusing on water systems and ways to store the water from flooding or slow its discharge into rivers. The country created a Room for the River program to give rivers more space to flood. Next, they began working with nature, letting the water in and creating lakes, garages and parks that transform into emergency reservoirs during flooding.

"We've gone from flood protection to flood risk reduction to flood resilience," Heuer says. "Now we focus on the third level, which is more like flood resilience, what I see as a combination of measures."

Experts at Royal HaskoningDHV have learned local involvement is vital, whether it's in Vietnam, Great Britain, the United States or Australia, all countries where the firm has projects. "What fits local stakeholders and the local needs best?" she adds. "Those are key elements."

In Vietnam's Mekong Delta, for instance, her firm's plan allows the river to expand, creating controlled flood plains in the north while restoring mangroves along the coast to provide natural protection. Along the east coast of England, sandscaping, something pioneered in the Netherlands, creates protection against erosion by depositing sand so waves and winds distribute it along the coast and create dunes to buffer the soft cliffs.

Rising seas threaten 10 percent of the world’s urban population so there’s never-ending demand. Dutch companies have worked in Houston, Miami, New York, Charleston, Jakarta, Bangkok, Dhaka and Shanghai.

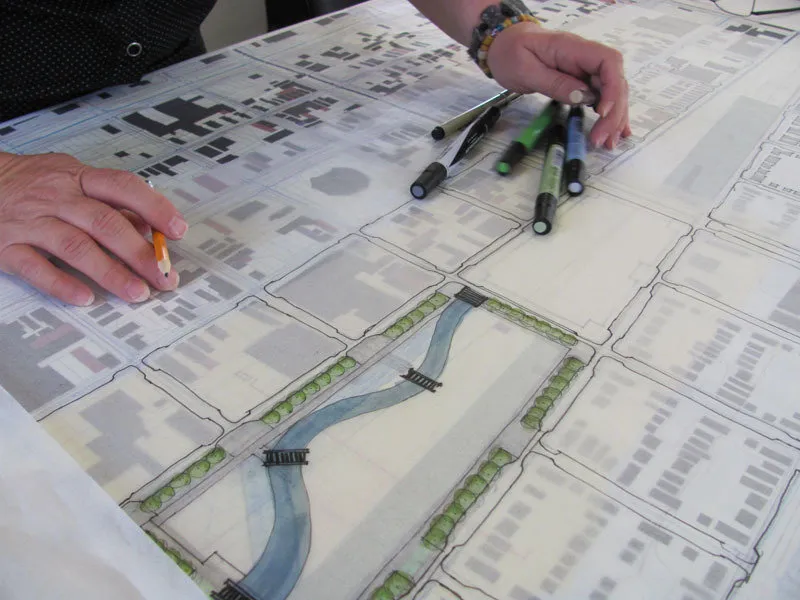

In New Orleans, Waggonner and his Dutch partners brought together landscape architects, hydrologists, urban planners, politicians, community leaders and engineers first to talk and then to design plans for the city. The result is Living with Water, the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, a 50-year program of retrofits and urban design strategies that emphasize slowing and storing stormwater rather than pumping, circulating surface water and recharging groundwater. The plan declares that "Water is a fact of life on the delta. Making space for water and making it visible across the urban landscape allows it once again to be an asset to the region."

Waggonner says understanding the local hydrology and then letting design, not public policy, drive the process was a new way of looking at the city’s problems. "The benefit for us was that over the period of time of getting the Dutch Dialogues going, we found people with similar minds but who had different skills, people who know something that you don't," he adds.

In the years since, New Orleans has initiated more than $120 million in green infrastructure projects, including rain gardens and a requirement passed by City Council in September that businesses use permeable paving in new parking lots. Mirabeau Water Garden, a $30 million demonstration project on a 25-acre site that will provide both recreation and water retention, is scheduled to begin construction in the spring of 2020. But challenges abound. An investigation into 2017 flooding cited aging infrastructure as a problem and urged a more aggressive embrace of the Urban Water Plan. Meanwhile, a retooled levee system that cost $14.6 billion is already sinking and doesn’t guard against heavy rains.

The most recent Dutch Dialogues was completed in Charleston, South Carolina, this summer. Mayor John Tecklenburg said at the conclusion of the talks that the city hasn’t acknowledged the power of water during its 350 years, filling in creeks and building over marshes. Now, he says, the city should consider where water wants to go as it makes future planning, land use, development and redevelopment choices.

In Charleston, the consultants, which included the Dutch and Waggonner & Ball, created a 250-page report. Broadly, the plan advocates a combination of man-made and natural solutions. “Some hard infrastructure has been and will always be needed to sustain settlements in the Lowcountry, but water and wetlands determined historic patterns of living and building,” it notes. “Land that was once naturally wet, will be again.”

Among its specific recommendations are to build the Low Battery higher protecting downtown, something already planned; consider raising a street atop a sea wall in the medical district; and create ways to slow stormwater moving from higher ground to the harbor on the city’s eastside.

The report noted that three-quarters of local businesses reported impacts from storms and flooding and 44 percent reported loss of income. “This is economically unsustainable,” it concluded.

In Norfolk, Homewood says the city's thinking changed radically after holding the dialogues in 2015. "We were going to build walls. We were going to build tall,” he says. “We couldn't figure out how we were going to pay for it, but we were going to find somebody. Then we have this Dutch dialogue and we realized, wait a minute, we have an opportunity to learn to live with water. More importantly, we can start thinking of water not as this existential threat, but as an asset."

The city looked at old maps and found that it was flooding where it had filled creeks and wetlands. "We had the hubris to think that we could engineer our way into a better city and we ended up making it worse for future generations," he adds.

Living with water, not just flooding from the occasional hurricane, is what Norfolk is facing. Sunny day tidal flooding is increasing. So is the intensity and frequency of storms that dump inches of water within minutes. Couple that with an antiquated stormwater system and the city needed to explore new ideas.

That's what it's doing with a $112 million project funded by a Housing and Urban Development grant to create resilience for two neighborhoods, one with 400 houses and the other with 300 public housing units, in a watershed. Early visions called for a series of seawalls with five huge pumps to drain the area, but consulting with the Dutch changed directions. Now, there will be a combination of hard infrastructure, including a tide gate, the raising of roads and improved stormwater capacity, combined with nods to nature. The plans include a resilience park connecting the neighborhoods that features a berm, a restored tidal creek and wetland, as well as sports fields, a picnic grove and a "water walk" along a tidal creek. A creek will be expanded, providing for water storage. Green infrastructure, including permeable pavers, will filter runoff and reduce street flooding. Construction is scheduled to begin soon.

Like the plans envisioned for New Orleans, that means residents will engage with water more often. That's the point.

"One of the things we keep saying is that in some projections we will have 45 days of nuisance flooding a year," Homewood says. "That number sounds like, wow. But, on the other hand, that means you've got 320 days without nuisance flooding. That's the kind of thinking that came out of the Dutch Dialogues. Don't focus on the negative. Look at the positive."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)