Could a Bra Actually Detect Breast Cancer?

Using thermodynamic sensors, the iTBra could one day screen for breast cancer, but experts are wary

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/42/214232d9-aea2-4dec-a743-8599dd0db30d/itbra.jpg)

For more than a decade, researchers have been interested in developing a bra embedded with thermodynamic sensors that could help screen for breast cancer. Cyrcadia Health, previously First Warning Systems, has been working toward this goal since 2008. Most recently, the company, in partnership with Cisco and Ironbound Films, released the trailer of a documentary called “Detected” at SXSW. The film follows Cyrcadia’s development of the iTBra through prototypes and clinical trials.

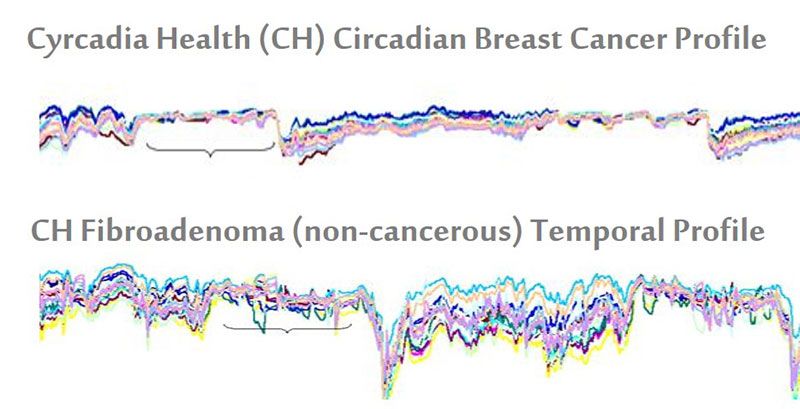

The iTbra uses heat sensors that track the temperature fluctuations in a woman’s breasts, and from this data maps out a wearer’s circadian pattern, or daily norms. The pattern is then relayed from the bra to a computer by USB and run through predictive analytics the company has developed to determine whether or not it signals the presence of cancer. Rob Royea, the CEO of Cyrcadia Health, explains: if a flattened circadian profile is identified, it may be indicative of cancer in the same way a flattened EKG profile is indicative of cardiac arrest.

What Royea means is this: for a healthy individual, there is likely to be a high degree of temperature variation over a normal 22 to 26 hour cycle. Exercise, hot flashes and sleep will all cause shifts in a woman's baseline temperature. However, individuals with breast cancer typically have temperature profiles that are consistently compressed, with little variation.

Users must wear the bra for a length of time between two and 24 hours for each respective screening, in order for it to gather the data necessary for this map to be generated. The technology that Cyrcadia has developed currently lives in patches that can be adhered to any bra, but the company is building an integrated sports bra in partnership with Flextronics. This version will be Bluetooth- and WiFi-enabled, allowing wearers to share their information with family and friends for support.

According to Royea, the product, now in clinical testing, has come a long way since he first started working on it. “When I came aboard, I was presented with an analog device that looked like an angry octopus," he says. "The question was: can this technology evolve into something that can be scalable?”

The premise behind the product is certainly a good one. A bra of this type could conveniently and inexpensively monitor the wearer between self-exams and regular breast cancer screenings. But what the company is still missing is comprehensive data to support its claims, says H. Gilbert Welch, a professor at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine and the author of Less Medicine, More Health. While it is an attention-grabbing invention, gathering sufficient data will be an important move for Cyrcadia to validate the effectiveness of the iTBra.

“It is way too early to suggest that monitoring circadian temperature changes in the breast will help anybody," says Welch. “While it’s tempting to believe 'newer is always better,' this is a totally untested technology that may well prove to produce more harm than good.”

Elaine Schattner, an associate professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and medical journalist, adds, “The iTBra is essentially an untested, commercial device that may tempt some women who don't want to go through the hassle and alleged risks of mammography. It's not plausible that such a contraption would detect early-stage breast cancer in many or most cases. Women who wish to be screened for breast cancer would be wiser, instead, to go with a proven method.”

Royea and his team created the product in response to two key gaps they observed in the breast cancer screening process today. For women with dense breast tissue, mammography has been found, in certain cases, to be less effective. He believes that using this technology may someday provide an alternative or supplementary option. The iTBra could also potentially be used post-mammography to determine whether a biopsy is required. Today, 80 percent of breast biopsies are done on non-cancerous tissue.

Thus far, Cyrcadia has conducted clinical trials with 500 women in partnership with Ohio State University. While it is a small sample size, the results showed that the iTBra was 87 percent accurate when it came to correlating tumors with cancer. Mammography is 83 percent accurate. Within the next six months, under the guidance of lead principal investigator, Joshua D. I. Ellenhorn, professor of surgery at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, the company will conduct more trials at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, California in parntership with the Canary Center at Stanford, as well as another large-scale trial including 10,000 women in India and Singapore. These locations were chosen, says Royea, because of the company’s partnerships and the growing incidence rate for cancer in Asia.

In response to skeptics, Royea points to existing research on the relationship between temperature and cancer cell division that has laid a foundation for the product. He expects that the upcoming trials and support of physicians, including William Farrar, chief of surgical oncology at Ohio State University, who will serve as Cyrcadia's acting Chief Medical Officer, will provide more validation.

Depending on the trials’ results, Cyrcadia plans to release the product in Asia and Europe in early 2016. Waiting for FDA approval, the company hopes to launch in the U.S. later that year. The product provides a “low-cost” option, says Royea, estimating it to cost less than $99 for a version that women could use for monthly screenings. In addition to the consumer version, the company is focusing on a product for oncologists to use to scan patients to insure that biopsies are necessary.

Seth Kramer, the filmmaker behind the Detected documentary, which will be released later this year, was drawn to telling this product’s story because of its interesting confluence between the “Internet of Things” and medical advances. “It’s a glimpse into the future,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)