Could a Pill Help Detect Breast Cancer?

University of Michigan researchers are developing a pill that when ingested causes tumors to glow under infrared light

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/5b/1b5b81cc-61fb-429d-b9a9-f2cbab21f53d/diagnostic-pill-microscope-image.jpg)

Women eventually face the yearly ritual of the mammogram, usually suggested from age 50 onwards. It's not painful, though notoriously uncomfortable, as two plates flatten the breasts, pancake-like, to get the best possible picture. The radiologist then looks at x-ray images for opaque spots that can indicate tumors.

Mammography has been used since the late 1960s and is considered the gold standard for breast cancer detection. But it’s far from perfect. The method misses about 1 in 5 cancers, and about half of women screened annually for 10 years will have a false positive result, often resulting in anxiety and unnecessary biopsies. Mammograms are also unable to distinguish slow-growing cancers from aggressive ones, which is necessary when choosing a course of treatment.

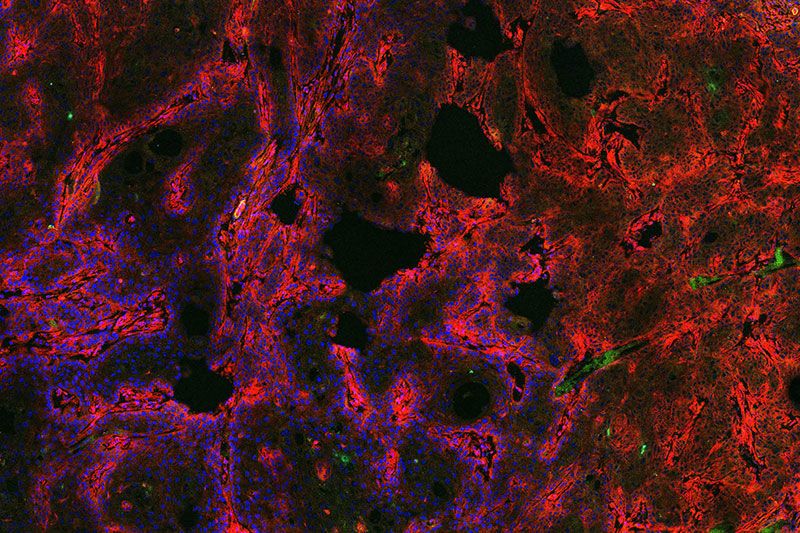

But researchers at the University of Michigan are working on a new method of breast cancer detection they hope could complement—perhaps one day even replace—the mammogram. It’s a pill—patients swallow it and it makes tumors light up when exposed to infrared light. The pill could not only detect tumors, it could also potentially distinguish how aggressive they are.

“From decades of research into cancer, we know it’s really a molecular disease,” says Greg Thurber, a professor of chemical and biomedical engineering who led the research, recently published in the journal Molecular Pharmaceutics. “But the screening technology just looks at anatomy.”

Thurber’s team developed a pill filled with dye that “tags” a molecule common in tumors and the surrounding tissue. Once the pill has been ingested, researchers can use infrared light to penetrate the breast (the exact technology is under development). This both reveals the presence of tumors and gives information on the types of molecules present in these tumors, which can help doctors determine the nature of the cancer.

Taking the dye in pill form is potentially safer than having it injected intravenously, which can occasionally cause allergic reactions. But designing the pill was a challenge. The kind of molecule that can be easily absorbed in pill-form by the digestive tract needs to be small and “greasy,” Thurber says, while molecules that make good imaging agents are larger and bind to water.

To find the right agent, the team used a combination of lab testing and computer modeling. They eventually got lucky when they found that the pharmaceutical company Merck had a cancer drug they’d tested for safety but had proven ineffective in clinical trials. The drug turned out to be perfect for the team’s purposes, as it was capable of passing freely through the bloodstream and binding to tumor molecules. They added a molecule that lights up under infrared light, and tested the resulting combo in mice with breast tumors. Indeed, it made the tumors glow.

Thurber and his team are now focused on developing additional agents to add to the current pill that could tag different types of tumors or different aspects of tumors. This could give doctors additional information about the cancers detected.

“Every person’s tumor is different,” Thurber says. “Even within the same tumor there can be different types of cancer.”

The researchers will then need to do toxicity studies and from there move to larger animal studies. Thurber hopes they can reach the human trial phase in about five years. They’re also hoping to partner with companies to develop the infrared screening tools necessary for human use.

While the pill could theoretically tag any type of cancer, infrared light can only penetrate a short distance into the body. This is fine for breast cancer detection, as breasts can be “squished” thin for imaging, but wouldn’t work for detecting cancer in deeper organs.

The team does hope the approach could work for detecting other diseases besides cancer. Rheumatoid arthritis is one potential target, Thurber says, as it is can be effectively treated in its early stages, but is hard to distinguish from other types of arthritis until it progresses.

Reuven Gordon, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Victoria in Canada who studies the use of light in cancer detection, thinks the research is promising but cautions that it’s early days. Even if a new method of detection is useful, researchers will have to prove that it’s better than the gold standard, and work to make clinicians and patients comfortable with new technology.

“It’s not obvious to me that this is going to be a home run, but it does look promising,” he says. “They have demonstrated something nice from a scientific point of view.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)