Could ‘Nanowood’ Replace Styrofoam?

Scientists at the University of Maryland have developed a biodegradable material that is both strong and a good insulator

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/a7/81a7d8cf-5a93-4851-a921-bcac0922e708/nanowood.jpg)

Expanded polystyrene (or “Styrofoam”) is an excellent insulator. That's why it’s a popular material for insulating buildings—and why those cheap little cups of deli coffee still burn your tongue after 30 minutes. But its environmental record leaves something to be desired. It’s nonbiodegradable, harmful to animals who accidentally eat it, and made from potential carcinogens.

Researchers at the University of Maryland have developed a super-lightweight insulating material they say could prove to be a better, more eco-friendly alternative. The material, made from tiny wood fibers, is called nanowood. It blocks heat at least 10 degrees better than Styrofoam or silica aerogel, a common insulator, and it can take at least 30 times more pressure than Styrofoam or silica aerogel before being crushed.

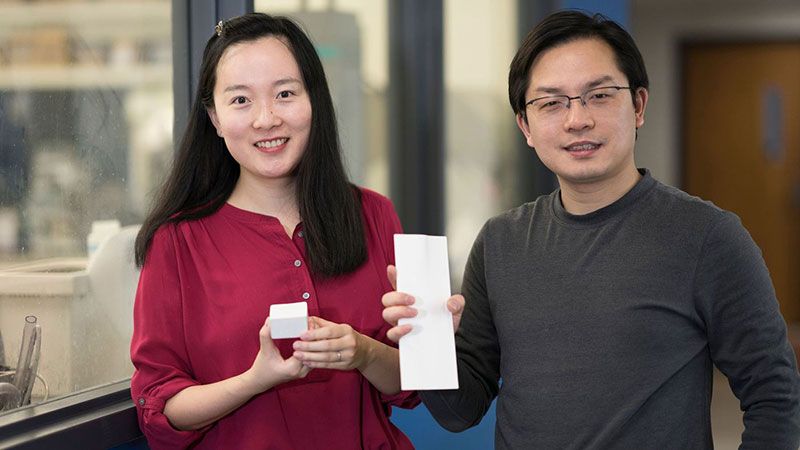

Working in the lab of materials scientist Liangbing Hu, postdoctoral researcher Tian Li is the lead author on the study, published this month in the journal Science Advances.

“To the best of our knowledge, the strength of our nanowood represents the highest value among available super insulating materials,” wrote the study authors.

Hu and his team had been working on nanocellulose, the nano-sized versions of the fibrous material that makes plants and trees rigid. Nanocellulose has an impressive strength-to-weight ratio, about eight times greater than that of steel.

For the nanowood, the team removed the lignin, the polymer that holds the cellulose of wood together. Removing the lignin, a heat conductor, gave the resulting product powerful insulating capabilities. It also turned the product white, which means it reflects light.

The researchers think nanowood has enormous potential as a green building material. Using it could potentially “save billions” in energy costs says Li. In addition to using it where traditional insulators like Styrofoam are used, thin strips of nanowood can be rolled and shaped to insulate the insides of pipes or other curved spaces. And unlike glass or wool insulators, nanowood doesn’t irritate lungs or cause allergic reactions.

“What I find impressive about nanowood, as described in the paper, is that the treatment process that the authors developed allows them to keep key features of wood—particularly its hierarchical structure across length scales from nano to macro, while dramatically altering other key properties, particularly thermal conductivity and optical reflectivity,” says Mark Swihart, a professor of chemical and biological engineering at the University at Buffalo who studies nanomaterials.

Synthetically recreating the hierarchical structures of natural materials like wood is extremely difficult, Swihart says, but the University of Maryland process seems to be simpler and more scalable than most methods of producing nanostructured materials.

Swihart thinks nanowood may one day be a useful material on the commercial market, but it may be a while. “For the foreseeable future, the material is inherently going to be more expensive than alternatives already produced at large scale, such as various types of foam board,” he says. “Even though it may outperform those alternatives, if it performs the same basic function, then entering the market will be very challenging.”

The University of Maryland team is more optimistic about nanowood’s near-term potential. They say the material can be produced fairly cheaply and quickly using fast-growing trees like balsa. The team is currently working on commercial applications and expect a product to be available in a year or so.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)