This Device Can Hear You Talking to Yourself

AlterEgo could help people with communication or memory problems by broadcasting internal monologues

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/b2/1db2f0b5-8a39-4ffd-9eef-ee0b5850acd8/alterego-main.jpg)

He’s worked on a lunar rover, invented a 3D printable drone, and developed an audio technology to narrate the world for the visually impaired.

But 24-year-old Arnav Kapur’s newest invention can do something even more sci-fi: it can hear the voice inside your head.

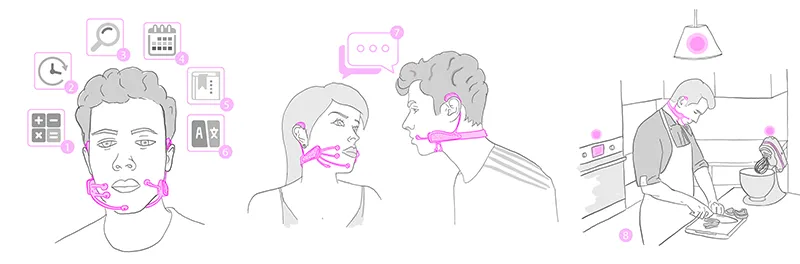

Yes, it’s true. AlterEgo, Kapur’s new wearable device system, can detect what you’re saying when you’re talking to yourself, even if you’re completely silent and not moving your mouth.

The technology involves a system of sensors that detect the minuscule neuromuscular signals sent by the brain to the vocal cords and muscles of the throat and tongue. These signals are sent out whenever we speak to ourselves silently, even if we make no sounds. The device feeds the signals through an A.I., which “reads” them and turns them into words. The user hears the A.I.’s responses through a microphone that conducts sound through the bones of the skull and ear, making them silent to others. Users can also respond out loud using artificial voice technology.

AlterEgo won the “Use it!” Lemelson-MIT Student Prize, awarded to technology-based inventions involving consumer devices. The award comes with a $15,000 cash prize.

“A lot of people with all sorts of speech pathologies are deprived of the ability to communicate with other people,” says Kapur, a PhD candidate at MIT. “This could restore the ability to speak for people who can’t.”

Kapur is currently testing the device on people with communication limitations through various hospitals and rehabilitation centers in the Boston area. These limitations could be caused by stroke, cerebral palsy or neurodegenerative diseases like ALS. In the case of ALS, the disease affects the nerves in the brain and spinal cord, progressively robbing people of their ability to use their muscles, including those that control speech. But their brains still send speech signals to the vocal cords and the 100-plus muscles involved in speaking. AlterEgo can capture those signals and turn them into speech. According to Kapur’s research, the system is about 92 percent accurate.

Kapur remembers testing the device with a man with late-stage ALS who hadn’t spoken in a decade. To communicate, he’d been using an eye-tracking device that allowed him to operate a keyboard with his gaze. The eye-tracking worked, but was time-consuming and laborious.

“The first time [AlterEgo] worked he said, ‘today has been a good, good day,’” Kapur recalls.

The device could also “extend our abilities and cognition in different ways,” Kapur says. Imagine, for example, making a grocery list in your head while you’re driving to the store. By the time you’re inside, you’ve no doubt forgotten a few of the items. But if you used AlterEgo to “speak” the list, it could record it and read back the items to you as you shopped. Now imagine you have dementia. AlterEgo could record your own instructions and give reminders at an appropriate time. Potential uses are nearly endless: you could use the system to talk to smart home devices like the Echo, make silent notes during meetings, send text messages without speaking or lifting a finger. AlterEgo could even one day act as a simultaneous interpreter for languages—you’d think your speech in English and the device would speak out loud in, say, Mandarin.

“In a way, it gives you perfect memory,” Kapur says. “You can talk to a smarter version of yourself inside yourself.”

“I think that they’re a little underselling what I think is a real potential for the work,” says Thad Starner, a professor in Georgia Tech’s College of Computing, speaking to MIT News.

The device, Starner says, could be useful in military operations, such as when special forces need to communicate silently. It could also help people who work in noisy environments, from fighter pilots to firefighters.

Kapur has applied for a patent for AlterEgo and plans to develop it into a commercial device. Right now he’s working on optimizing the hardware to process extremely high volumes of data with minimal delay, and on refining the A.I.

Kapur hopes AlterEgo can help people see A.I. not as a scary, evil force here to steal our identities and our jobs, but as a tool that can improve our everyday lives.

“Somewhere in the last 20 or 30 years we forget that A.I. was meant to enable people,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)