Doctors Are 3D Printing Ear Bones To Help With Hearing Loss

By printing custom bone prostheses, researchers hope they can better fix a certain kind of hearing loss

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/36/1436dc36-f85f-4c64-a30f-a83ea740ec6e/3dear2.jpg)

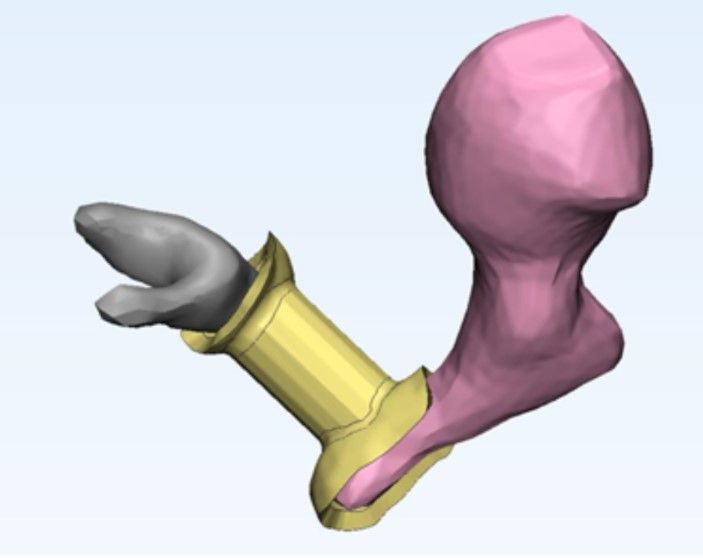

The auditory ossicles of the middle ear – the malleus, incus and stapes – are the tiniest bones in the human body. All three can fit on a dime, with room to spare. Their job is to transmit sounds from the ear drum to the liquid of the inner ear. Illnesses, accidents and tumors can damage these bones, causing what’s known as “conductive hearing loss.” The remedy is a delicate surgery, in which the bones are replaced with a tiny prosthesis. But the surgery has a relatively high failure rate, about 25 to 50 percent.

Now, researchers at the University of Maryland Medical Center are using 3D printers to make custom-fitted ear bones. They hope these prostheses will improve on the current technology and raise the success rate of surgery.

The team, made up of a radiologist and two ear, nose and throat doctors, took the ossicles from three human cadavers and removed the middle bones, or incuses. They then used a CT scanner to take images of the gaps left by the incuses, and designed tiny prostheses to fit those gaps. The prostheses varied by just fractions of millimeters, with ever so slightly different angles.

The researchers then gave four different surgeons the three prostheses and had them guess which one went in which ear. Each surgeon independently matched the prostheses to the correct ears.

“They said it wasn’t that hard to figure out,” says Jeffrey Hirsch, a radiology professor who led the research. “It was almost like a Goldilocks sort of thing – this prosthesis was too tight in this ear and too loose in this ear, but in this ear it’s just right.”

The research was published recently in the journal 3D Printing in Medicine.

The next step will be to test the prostheses for function using cadavers or animal models. They can run vibrations through a prosthesis to see how it transmits sound.

There will be some significant challenges to overcome before the prosthesis would be ready for human use. The CT images used to create the prostheses were made with cadaver skulls that had been cut down to include only a part of the surrounding bone. In a live human with an intact skull, these images may be more challenging to achieve.

Then there’s the question of material. The prototypes used in the study were made from a polymer that’s not FDA approved for permanent implantation in humans. So the team will eventually need to find a biocompatible material. They’re also experimenting with whether the prosthesis can be designed with a waffle-like texture to make it a scaffolding for stem cells. Then, in theory, the prostheses could be made of real bone, which would reduce the risk of rejection.

In recent years, a number of researchers have used 3D printing to create external ears or ear parts. Researchers in the UK and California used stem cells to grow ears on 3D printed scaffolds to treat children with microtia, a congenital malformation of the external ear. Researchers at Wake Forest University have been creating external ear parts with a 3D printer using living cells and biodegradable polymers.

“Various groups of investigators are targeting the printing of ear parts due to the need of improved technologies for patients with hearing loss,” says Anthony Atala, director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Atala says the University of Maryland research is “very promising, as these structures play an integral role in the function of hearing inside the ear.”

The role of 3D printing in regenerative medicine is not limited to ears, of course. Researchers, including Atala and his team, have been working on developing 3D printing technology for all sorts of body parts, from skin to bones to kidneys. In 2012, researchers implanted a 3D printed temporary windpipe in a baby who’d been born with a congenital defect that caused his bronchial tubes to collapse.

“I really think that 3D printing is going to become a standard of care whenever there’s a need for a prosthesis, whether it be a joint or a middle ear,” says Hirsch. “The standard of care will not be an off-the-shelf component, but a component that’s custom designed for that specific patient.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)