Does Fish Skin Have a Future in Fashion?

To promote sustainability in the industry, designer Elisa Palomino-Perez is embracing the traditional Indigenous practice of crafting with fish leather

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/66/8166a06f-6688-451e-8deb-a908f5b36029/elisa_palomino-perez-clutch.jpg)

Elisa Palomino-Perez sheepishly admits to believing she was a mermaid as a child. Growing up in Cuenca, Spain in the 1970s and ‘80s, she practiced synchronized swimming and was deeply fascinated with fish. Now, the designer’s love for shiny fish scales and majestic oceans has evolved into an empowering mission, to challenge today’s fashion industry to be more sustainable, by using fish skin as a material.

Luxury fashion is no stranger to the artist, who has worked with designers like Christian Dior, John Galliano and Moschino in her 30-year career. For five seasons in the early 2000s, Palomino-Perez had her own fashion brand, inspired by Asian culture and full of color and embroidery. It was while heading a studio for Galliano in 2002 that she first encountered fish leather: a material made when the skin of tuna, cod, carp, catfish, salmon, sturgeon, tilapia or pirarucu gets stretched, dried and tanned.

“[Fish skin] was such an incredible material. It was kind of obscure and not many people knew about it, and it had an amazing texture. It looked very much like an exotic leather, but it's a food waste,” Palomino-Perez says. “I've got a bag from 2002 that, with time, has aged with a beautiful patina.”

The history of using fish leather in fashion is a bit murky. The material does not preserve well in the archeological record, and it’s been often overlooked as a “poor person’s” material due to the abundance of fish as a resource. But Indigenous groups living on coasts and rivers from Alaska to Scandinavia to Asia have used fish leather for centuries. Icelandic fishing traditions can even be traced back to the ninth century. While assimilation policies, like banning native fishing rights, forced Indigenous groups to change their lifestyle, the use of fish skin is seeing a resurgence. Its rise in popularity in the world of sustainable fashion has led to an overdue reclamation of tradition for Indigenous peoples.

In 2017, Palomino-Perez embarked on a PhD in Indigenous Arctic fish skin heritage at London College of Fashion, which is a part of the University of the Arts in London (UAL), where she received her Masters of Arts in 1992. She now teaches at Central Saint Martins at UAL, while researching different ways of crafting with fish skin and working with Indigenous communities to carry on the honored tradition.

“For the past four years, I have been traveling all around the world, connecting all these incredible elders, all these Indigenous people—the Ainu on Hokkaido Island in Japan, the Inuit, Alutiiq and Athabaskan in Alaska, the Hezhen in Northeast China, Sami in Sweden and Icelanders—and studying different technology of fish skin,” she says.

Traditionally, the Ainu people in Japan used salmon skin for boots, similar to the Inuit, Alutiiq and Athabaskan in Alaska, who also used the skin for mittens, parkas and clothing. While this practice was once essential to survival, it also held spiritual significance with the afterlife and water deities in communities that believe that people must cross a river from this world to the next after death. But the fish skin tradition eventually declined in the 20th century, due to colonialism, assimilation and changing policies and laws affecting Indigenous groups.

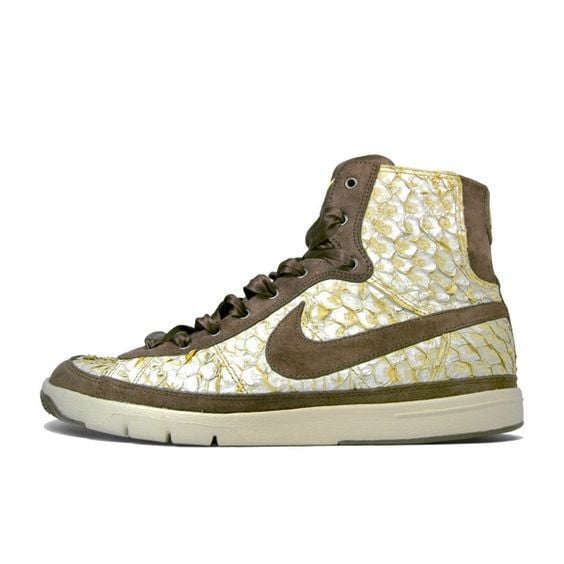

Most recently, Palomino-Perez took part in an anthropology fellowship, and is now a research associate, at the National Museum of Natural History’s Arctic Studies Center in Washington D.C. Beginning in December 2020, the designer studied—virtually from her home in Italy, due to the Covid-19 pandemic—fish leather baskets, boots and mittens in the Smithsonian’s collection, from communities like the Inuit people of Alaska, Yup’ik people of Kuskokwim River in Southwest Alaska and the Alutiiq on Kodiak Island. These artifacts and her conversations with Indigenous elders in Alaska inspired her to create fish skin bags and sneakers. One of her clutches, for example, has plant-like designs digitally printed in water-based inks of soft pinks, oranges and tans onto fish leather. Palomino-Perez is now trying to put together a fish skin coalition with artists from Alaska, Japan, Iceland, Siberia and northeast China to collaborate and explore fish skin fashion and technology.

“Here's something from the past, it pretty much had been forgotten, and yet, it's now being revived and has tremendous socially and environmentally laudable goals,” says Stephen Loring, museum anthropologist and an Arctic archaeologist working in the Smithsonian’s Arctic Studies Center.

According to Hakai Magazine, humans worldwide consumed a little under 150 million tons of filleted fish in 2015. One ton of filleted fish amounts to 40 kilograms of fish skin, and so in that year alone, the industry produced about six million tons of skins that could have been recycled. Obtaining the material isn’t as complicated as it might seem. Current commercial fish leather comes from sustainable farms operating in the same areas as tanners, who remove any excess meat off the fish skin and use tree bark, like Mimosa bark, to stretch, tan and dry the skin, as has been done in traditional processes. Agricultural farms that make fish fillets to be frozen supply tanners with their fish skin by-product.

While brands like Prada, Christian Dior, Louis Vuitton and Puma have used fish leather for clothes and accessories before, younger designers and startups are now showing interest—and Palomino-Perez is eager to normalize the practice. Sourcing her fish skin from Iceland, she designs, dyes and assembles her fashion accessories. She also works with a traditional indigo dyeing master in Japan, Takayuki Ishii, who grows the flowering plant, to dye her fish skin with stencils. A golden salmon skin clutch of hers is brilliantly contrasted with indigo floral-like patterns.

Palomino-Perez’s work will be featured at Smithsonian’s “FUTURES,” an interdisciplinary show opening at the Arts and Industries Building in Washington, D.C. in November and running through summer 2022. Part exhibition, part festival, “FUTURES” will highlight nearly 150 objects dedicated to different visions of the future of humanity.

“We ideated values that we think are going to be important to building a hopeful, sustainable and equitable future, and organized our content around those values,” says Ashley Molese, a curator for “FUTURES.”

The exhibit embraces a “choose your own adventure” model, according to Molese, which encourages visitors to explore the displays in any order. In the building’s West Hall, one of Palomino-Perez’s fish skin clutches will be on display next to a Yup'ik fish skin pouch handcrafted in Western Alaska and acquired by the National Museum of Natural History in 1921, as a way of connecting traditional objects and contemporary work from the same crafting process. This section of “FUTURES” focuses on the value of slowness, and innovation that isn’t technological and digital. Fish skin fashion is a testament to how the future of sustainability may find its salvation in time-honored traditions.

“These are living cultures, these aren't things of the past,” says Molese. “When we talk about Indigenous traditions, Indigenous practices, Indigenous cultures; they're still living and breathing.”

Molese adds: “We really wanted to have the visitor find something that is a unique moment for them in the show that helps build a sense of hope and agency that they could then embody, and then maybe even take action once they leave our doors.”

When it comes to using animal skins in fashion, fish skin proves to be one of the better options for the environment. At the end of the day, fish skin is food waste; it gets thrown back into the ocean or tossed away when companies process fish. From 1961 to 2016, the global per capita consumption of fish has grown from nine kilograms to a little over 20 kilograms a year, resulting in loads more discarded skin that could have a second life. While it’s pricier, and takes longer to process (about a week or so) compared to cow leather (a few days), fish skin is more durable, breathable and resistant. Working with fish skin ensures respect toward fish stocks and marine ecosystems and diverts attention away from endangered species used for fashion.

To do her part, Palomino-Perez has been working to ensure that fish skin crafting becomes even more sustainable. She has studied a tanning technique from the Indigenous Hezhen community in Northeastern China, that uses cornflower to soak in and remove the fish skins’ oils to create leather—a marked improvement from other tanning methods that can release harmful chemicals that pollute the air. With the University of Borås in Sweden, she will be developing ways to 3-D print with filaments made from tuna waste, instead of plastic. Additionally, Palomino-Perez has been organizing Zoom workshops led by Alutiiq Indigenous elder June Pardue and museum curators to train and teach individuals, like tanning artists, fashion students and other Indigenous people, the fish-crafting process. Eventually, she hopes fish skin will replace exotic skins in fashion. Producing natural and detailed items in a respectful way and without chemicals or harm toward the environment is the future, according to Palomino-Perez. “There's no other way to be working right now,” she says.

Palomino-Perez envisions fish skin material as both an empowering and natural concept in the future of fashion. She’s past the idea of “overpowering nature” and disrespecting animals, and is adopting a respect toward the planet and ourselves that Indigenous peoples have long embraced.

“There’s many people who are interested in the material,” she says, “so slowly, it’s picking up.”