The Dutch Designer Who Is Pioneering the Use of 3D Printing in Fashion

In a new exhibition, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta shows how Iris van Herpen started a high-tech movement

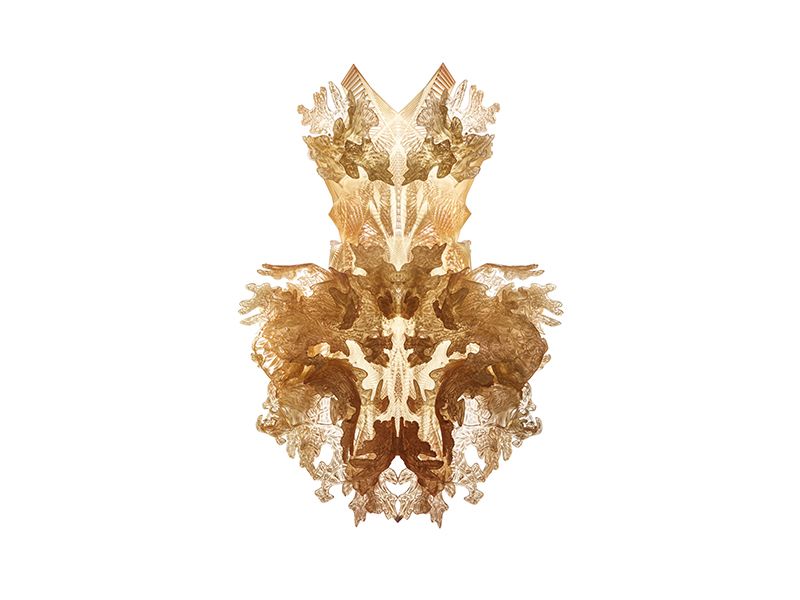

In 2011, Iris van Herpen made a splash when she debuted a 3D-printed dress—one of her first 3D-printed pieces—at Paris Haute Couture Fashion Week. The rigid garment resembled intricate white fabric scrunched-up into the shape of a Rorschach test. It was named one of the year's best inventions by Time magazine.

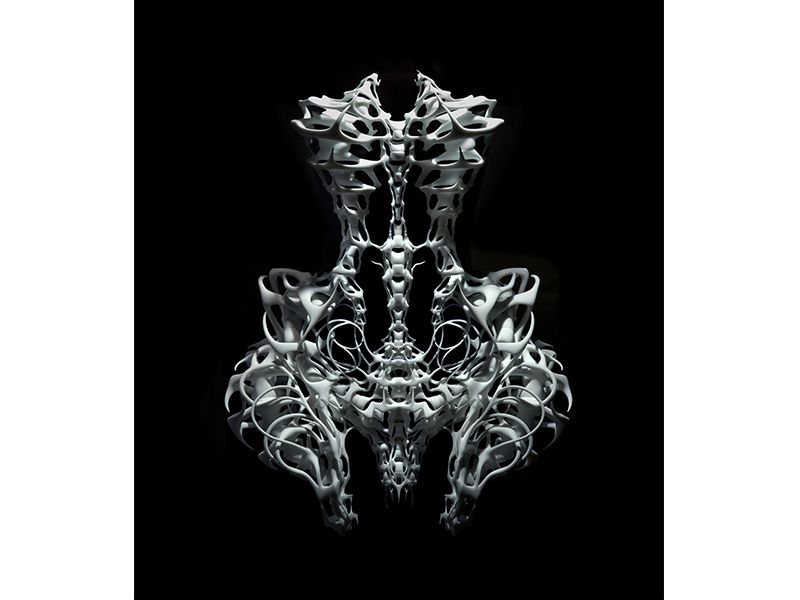

Van Herpen was the first designer to send 3D-printed couture down the runway, beginning in 2010. Since then, 3D-printing has become a hot new tool in the fashion industry, with major designers creating geometric cutout gowns, stiff and shiny trims and garments that resemble skeletons or Medieval armor. These innovations are mostly for runways, though a few have filtered into ready-to-wear. The luxury brand Pringle of Scotland has woven 3D-printed elements into the patterns and cuffs of its sweaters.

"Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion," the first major exhibition of the designer's work, will open at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta on November 7. The exhibition is a comprehensive survey, featuring 45 of van Herpen's most groundbreaking outfits from 2008 to the present, along with music and videos from her runways shows.

3D-printing technology has been around since the 1980s, and architects, engineers and industrial designers have been using the printers, which create objects layer by layer, to create models and prototypes for decades. There was an explosion of interest in the technique a few years ago, as the technology became more affordable and home printers debuted.

Van Herpen, who is in her early 30s, had a meteoric rise in the fashion industry. She studied fashion at the ArtEZ Institute of the Arts, Arnhem, in the Netherlands, and interned at Alexander McQueen in London. From an early age, she was interested in bringing new materials and processes into fashion, and she began designing womenswear under her own name a year after graduating from fashion school. At 27, she became the youngest designer named to the official calendar of Paris Haute Couture Fashion Week. Van Herpen pioneered the use of 3D printing for fashion, employing architects and engineers to help translate her designs into digital files that the printers can read. She began with rigid designs molded to the body and then expanded to flexible ones, as better materials, such as the rubber-like TPU 92A-1, became available.

“Iris van Herpen is fearless when it comes to experimenting with 3D printing and using the technology as a means to create the innovative designs that are her vision," says Sarah Schleuning, curator of decorative arts and design at the High Museum of Art, a Smithsonian affiliate museum. "She uses the technology not for its own sake, but to achieve spectacular effects that otherwise could not be realized."

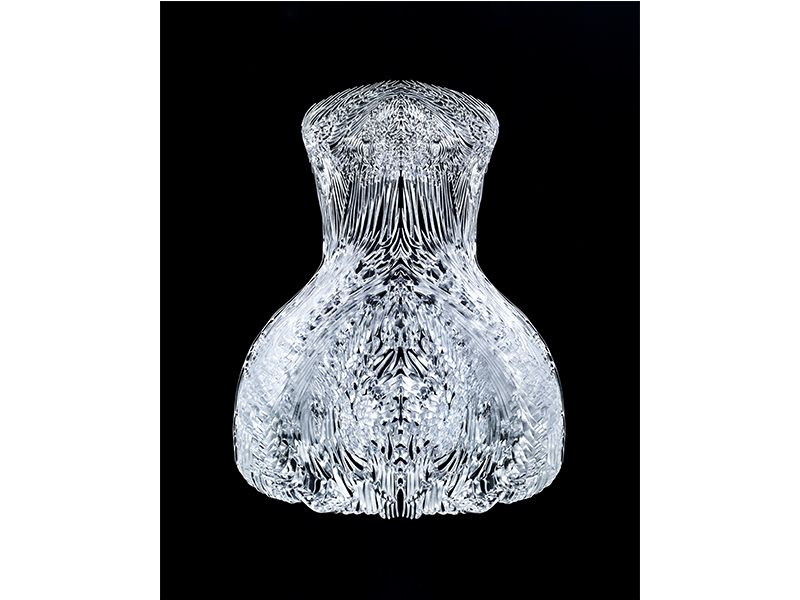

Adventurous style icons such as Björk and Lady Gaga have been drawn to van Herpen's pieces, perhaps because her work looks like wearable sculpture. A top from "Crystallization" (2010), her first collection to include 3D-printed elements, is rigid and looks like coral, with loops and ridges. A strapless dress from 2014 nicknamed "Ice Dress" resembles a single formation of ice with an intricate texture. The piece was printed on a state-of-the-art, industrial 3D printer, and the material is a transparent resin. Since the wearer cannot sit down, the piece is clearly intended only for the runway.

"When you look at the dress, the body underneath and the translucent texture merge, and they become one," van Herpen writes in an email. "This is possible because the dress is two pieces, with seams only on the sides, so the texture looks organic."

Sometimes the 3D-printed material is not the garment's structure, but simply an adornment, as in a 2014 dress that resembles a bird, with ribbons of 3D-printed material layered like feathers.

But 3D printing is not without its challenges. Since van Herpen's designs are elaborate, the digital files take a long time to create. And she can't see the finished product until she receives it back from the printing company.

"It remains a surprise how the dress will look," she writes. "In the past, I printed a dress and then found out it didn't look good in the material I chose."

As new materials emerge, designers have to learn their limitations, through experimentation. Jenny Wu is an architect who launched her own 3D-printed jewelry company, LACE, in 2014. Her work is printed in a variety of materials, including elastic nylon, hard nylon and stainless steel. "The tolerances are very different," Wu says. "Initially, my design might come back crumbled into pieces, or it might come back perfect. You have to learn to design to the material."

Van Herpen's 3D-printed designs inspired other designers, including Francis Bitonti, who printed a gown for Dita Von Teese featuring more than 3,000 unique, articulated joints, and Karl Lagerfeld, who adorned iconic tweed Chanel suits with 3D-printed details earlier this year. Fashion design students, too, are eager to experiment with 3D printing, though the cost often puts commercial 3D printing beyond their reach, and they need to learn the modeling software.

This spring, Danit Peleg, a student at Shenkar College of Engineering and Design in Israel, used a home 3D printer to create five garments for her graduate collection. Because the home printer was small, she had to print the material in pieces, and the project took more than 2,000 hours. The finished garments, made with a rubber-like material called FilaFlex, feature geometric cutouts—some delicate, some large—in bold colors.

"I felt like I was tinkering with the future," Peleg says. "I believe we're going to see the fashion industry change. Fashion houses will eventually have downloadable patterns on their websites, so people can print their clothes at home. We won't need to do production in Asia."

Experts warn, however, that it may take decades to arrive at such a future. Lynne Murray, director of the Digital Anthropology Lab at the London College of Fashion, says 3D printing for fashion is still a new concept. "It's a nice idea, to be able to 3D print clothes at home, or at your local corner shop, but it won't be a reality in the next 10 years,” she adds. “Maybe in 20 years, and maybe then the dress you get will also be able to change color or change shape." The Digital Anthropology Lab, which just opened this fall, gives the school's fashion students access to 3D printers, conductive textiles, wearable technology and body-scanning technology. Other major fashion schools, such as the Fashion Institute of Technology, Central Saint Martins and Parsons School of Design, have 3D printers and offer courses in how to use them.

"There will be a range of applications," Wu speculates, of the future. "There will be things to download and print yourself, but you'll also be able to get something really special that's designed by, and printed under the supervision of, an artist or fashion house."

"Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion" is on display at the High Museum of Art, a Smithsonian affiliate museum in Atlanta, through May 15, 2016.