Eight of Literature’s Most Powerful Inventions—and the Neuroscience Behind How They Work

These reoccuring story elements have proven effects on our imagination, our emotions and other parts of our psyche

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/51/e4/51e48449-03f2-44aa-a33f-1a897f16984e/neuroscience_and_reading.jpg)

Shortly after 335 B.C., within a newly built library tucked just east of Athens’ limestone city walls, a free-thinking Greek polymath by the name of Aristotle gathered up an armful of old theater scripts. As he pored over their delicate papyrus in the amber flicker of a sesame lamp, he was struck by a revolutionary idea: What if literature was an invention for making us happier and healthier? The idea made intuitive sense; when people felt bored, or unhappy, or at a loss for meaning, they frequently turned to plays or poetry. And afterwards, they often reported feeling better. But what could be the secret to literature’s feel-better power? What hidden nuts-and-bolts conveyed its psychological benefits?

After carefully investigating the matter, Aristotle inked a short treatise that became known as the Poetics. In it, he proposed that literature was more than a single invention; it was many inventions, each constructed from an innovative use of story. Story includes the countless varieties of plot and character—and it also includes the equally various narrators that give each literary work its distinct style or voice. Those story elements, Aristotle hypothesized, could plug into our imagination, our emotions, and other parts of our psyche, troubleshooting and even improving our mental function.

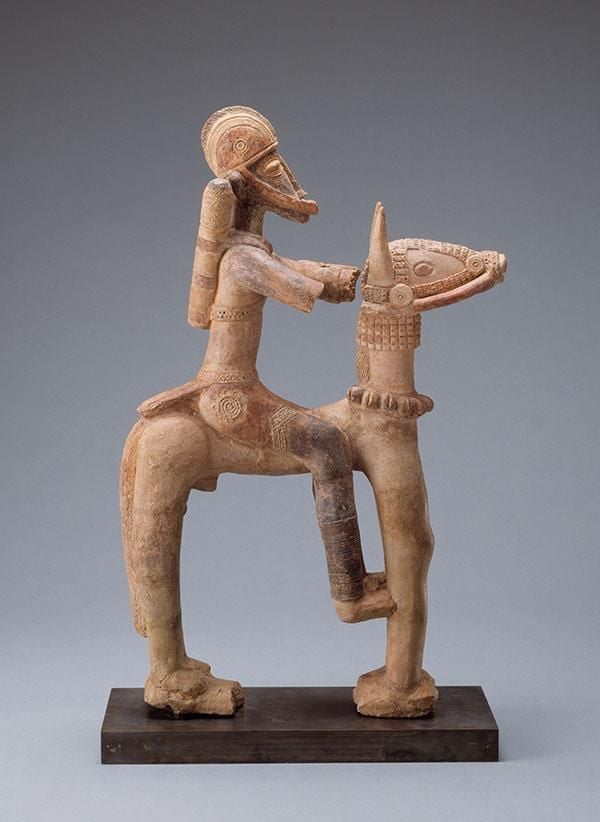

Aristotle’s idea was so unusual that, for more than two millennia, his account of literary inventions existed as an intellectual one-off, too intriguing to be forgotten but also too idiosyncratic to be developed further. In the mid-20th century, R. S. Crane and the renegade professors of the Chicago School revived the Poetics’ techno-scientific method, using it to excavate literary inventions from Shakespearean tragedies, 18th-century novels, and other works that Aristotle never knew. Later, in the early 2000s, one of the Chicago School’s students, James Phelan, co-founded Ohio State’s Project Narrative, where I now work as a professor of story science. Project Narrative is the world’s leading academic think tank for the study of stories, and in our research labs, with the help of neuroscientists and psychologists from across the globe, we’ve uncovered dozens more literary inventions in Zhou Dynasty lyrics, Italian operas, West African epics, classic children’s books, great American novels, Agatha Christie crime fictions, Mesoamerican myths, and even Hollywood television scripts.

These literary inventions can alleviate grief, improve your problem-solving skills, dispense the anti-depressant effects of LSD, boost your creativity, provide therapy for trauma (including both kinds of PTSD), spark joy, dole out a better energy kick than caffeine, lower your odds of dying alone, and (as impossible as it sounds) increase the chance that your dreams will come true. They can even make you a more loving spouse and generous friend.

You can find detailed blueprints for 25 literary inventions, including step-by-step instructions on how to use them all, in my new book, Wonderworks: The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature. And to give you a taste of the wonders they can work, here are eight basic literary inventions explained, starting with two that Aristotle unearthed.

Wonderworks: The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature

A brilliant examination of literary inventions through the ages, from ancient Mesopotamia to Elena Ferrante, that shows how writers have created technical breakthroughs—rivaling any scientific inventions—and engineering enhancements to the human heart and mind.

The Plot Twist

This literary invention is now so well-known that we often learn to identify it as children. But it thrilled Aristotle when he first discovered it, and for two reasons. First, it supported his hunch that literature’s inventions were constructed from story. And second, it confirmed that literary inventions could have potent psychological effects. Who hasn’t felt a burst of wonder—or as Aristotle called it, thaumazein—when a story pivots unexpectedly? And as modern research has revealed, that wonder can be more than a heart-exciting sensation. It can stimulate what psychologists term a self-transcendent experience (or what “father of American psychology” William James more vividly termed a “spiritual” experience), increasing our overall sense of life purpose.

That’s why holy scriptures brim with plot twists: Davids beating Goliaths, the dead returning to life, golden bowls floating upstream. That’s why the oldest complete Greek tragic trilogy—The Oresteia—ends with the goddess Athena performing a deus ex machina to flip violence into reconciliation. And that’s why we can get an emotional uplift from pulp-fiction twists like Obi-Wan Kenobi ghosting back in the original Star Wars to guide Luke Skywalker on his Death Star attack: Use the Force. . .

The Hurt Delay

Recorded by Aristotle in Poetics, section 1449b, this invention’s blueprint is a plot that discloses to the audience that a character is going to get hurt—prior to the hurt actually arriving. The classic example is Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus, where we learn before Oedipus that he’s about to undergo the horror of discovering that he’s killed his father and married his mother. But it occurs in a range of later literature, from Shakespeare’s Macbeth to paperback bestsellers such as John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars.

Aristotle hypothesized that this invention could stimulate catharsis, alleviating the symptoms of post-traumatic fear. And modern research—including Aquila Theatre’s NEH-funded outreach to military veterans, in which I was fortunate to myself participate—has supported Aristotle’s conjecture. That research has revealed that, by stimulating an ironic experience of foreknowledge in our brain’s perspective-taking network, the Hurt Delay can increase our self-efficacy, a kind of mental strength that makes us better able to recover from experiences of trauma.

The Tale Told From Our Future

This invention was created simultaneously by many different global authors, among them the 13th-century West African griot poet who composed the Epic of Sundiata. Basically, a narrator uses a future-tense voice to address us in our present. As it goes in the Epic: “Listen to my words, you who want to know; by my mouth you will learn the history of Mali. By my mouth you will get to know the story. . .”

In the late 19th century, this invention was engineered into the foundation of the modern thriller by authors such as H. Rider Haggard in King Solomon’s Mines and John Buchan in The Thirty-Nine Steps. Variants can be found in The Bourne Identity, Twilight and other modern pulp fictions that begin with a narrative flash-forward—and also in the many films and TV shows that open with a glimpse of an event to come. And no less than the two inventions that Aristotle dug up, this one can have a potent neural effect: by activating the brain’s primal information-gathering network, it boosts curiosity, immediately elevating your levels of enthusiasm and energy.

The Secret Discloser

The earliest-known beginnings of this invention—a narrative revelation of an intimate character detail—lie in the ancient lyrics of Sappho and an unknown Shijing poetess. And it exists throughout modern poetry in moments such as this 1952 love song by e. e. cummings:

"here is the deepest secret nobody knows

I carry your heart (i carry it in my heart)"

Outside of poetry, variants can be found in the novels of Charlotte Brontë, the memoirs of Maya Angelou, and the many film or television camera close-ups that reveal an emotion buried in a character’s heart. This construction activates dopamine neurons in the brain to convey the hedonic benefits of loving and being loved, boosting your positive affect and making you more cheerful and generally glad to be alive.

The Serenity Elevator

This element of storytelling is a turning around of satire’s tools (including insinuation, parody and irony) so that instead of laughing at someone else, you smile at yourself. It was developed by the Greek sage Socrates in the 5th-century B.C. as a means of promoting tranquility—even in the face of excruciating physical pain. And such was its power that Socrates’ student Plato would claim that it allowed Socrates to peacefully endure the terrible agony of swallowing hemlock.

Don’t try that at home. But modern research has held up Plato’s claim that the invention can have analgesic effects—and more importantly, that it can convey your brain into the serene state of feeling like it’s floating above mortal cares. If Plato’s dialogues are bit outdated for your reading style, you can find newer versions in Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Tina Fey’s “30 Rock.”

The Empathy Generator

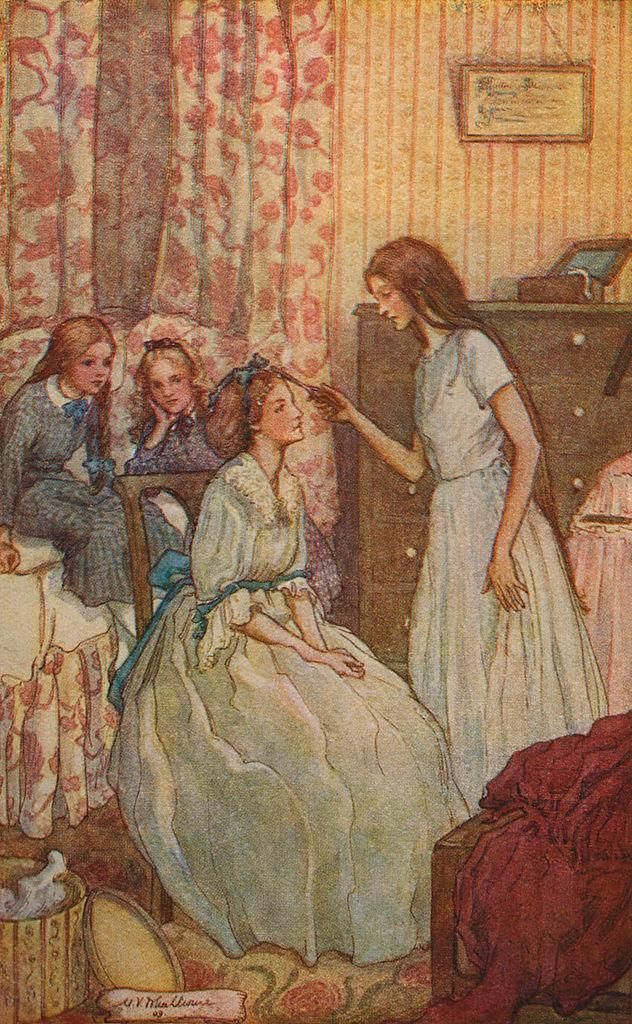

In this narrative technique, a narrator conveys us inside a character’s mind to see the character’s remorse. That remorse can be for a genuine error, like when Jo March regrets accidentally burning her sister Meg’s hair in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. Or it can be for an imagined error, like the many times that literary characters rue their physical appearance, personality quirks or other perceived imperfections. But either way, the invention’s window into a character’s private feeling of self-critique stimulates empathy in our brain’s perspective-taking network.

The invention’s original prototype was tinkered together by the anonymous Israelite poet who composed the verse sections of the Book of Job, likely in the 6th century B.C. Since empathy is a neural counterbalance to ire, it may have reflected the poet’s effort to promote peace in the wake of the Judah-Babylonian-Persian wars. But whatever the reason for its initial creation, the invention can help nurture kindness toward others.

The Almighty Heart

This invention is an anthropomorphic omniscient narrator—or, to be more colloquial, a story told by someone with a human heart and a god’s all-seeing eye. It was first devised by the ancient Greek poet Homer in The Iliad, but you can find it throughout more recent fiction, for example, in the opening sentence of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

The invention works by tricking your brain into feeling like you’re chanting along with a greater human voice. And that feeling—which is also triggered by war songs and battle marches—activates the brain’s pituitary gland, stimulating an endocrine response that’s linked to psychological bravery. So, even in the winter of despair, you feel a fortifying spring of hope.

The Anarchy Rhymer

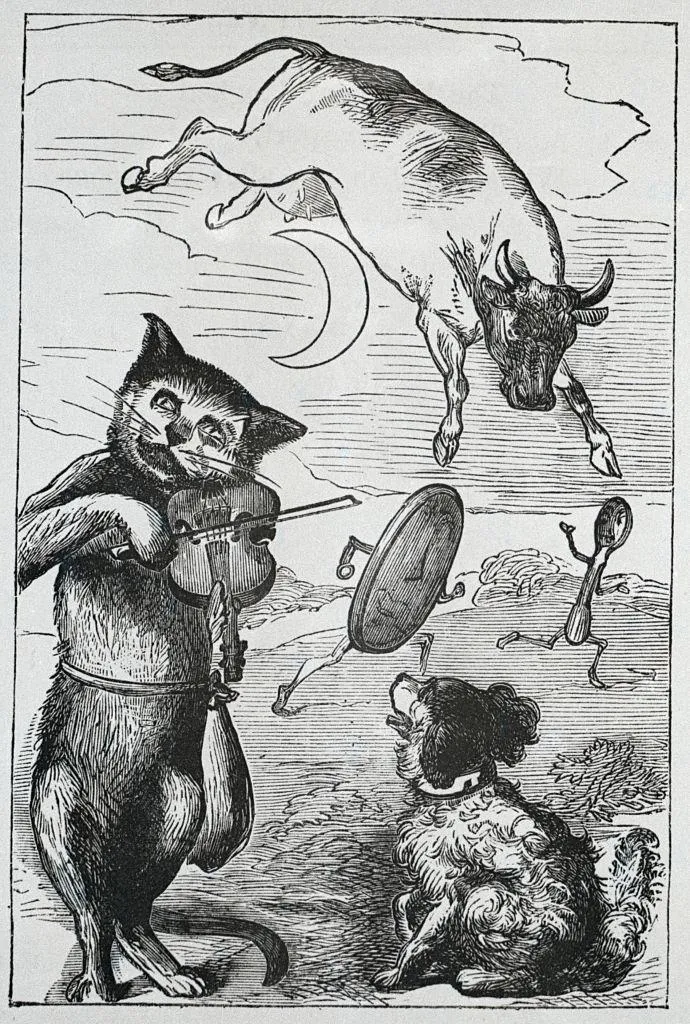

This innovation is the slipperiest of the eight to spot. That’s because it doesn’t follow rules; its blueprint is a rule-breaking element inside a larger formal structure. The larger structure was originally a musical one, as in this 18th century Mother Goose’s Medley nursery rhyme:

“Hey, diddle, diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,

The cow jumped over the moon;

The little dog laughed

To see such sport,

And the dish ran away with the spoon.”

You can easily spot the lawless elements, like the rebel dinnerware and the cow that doesn’t obey gravity. And you can hear the structure in the singsong cadence and chiming rhymes: diddle and fiddle; moon and spoon.

Since those early beginnings, the invention’s larger structure has evolved to assume narrative shapes, such as the regular geography of Christopher Robin’s Hundred Acre Wood (where the anarch is the merrily spontaneous Winnie-the-Pooh). But regardless of what form it takes, the invention activates a brain region known as the Default Mode Network, helping to boost your creativity.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.