The First African-American to Hold a Patent Invented ‘Dry Scouring’

In 1821, Thomas Jennings patented a method for removing dirt and grease from clothing that would lead to today’s dry cleaning

:focal(316x403:317x404)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/e1/eae1ad66-f156-467b-85e0-ebaf5527fffc/dry_cleaning.jpg)

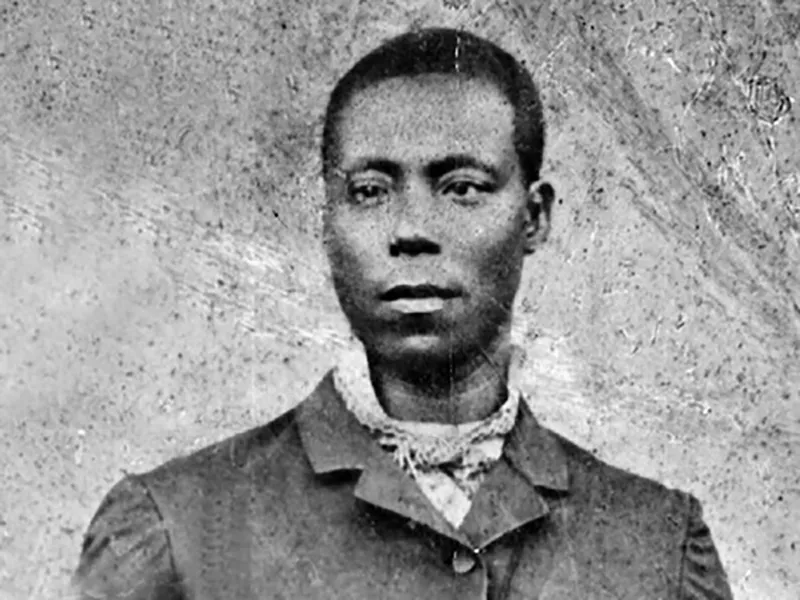

The next time you pick up your clothes at the dry cleaner, send a thank you to the memory of Thomas Jennings. Jennings invented a process called ‘dry scouring,’ a forerunner of modern dry cleaning. He patented the process in 1821, making him likely the first black person in America to receive a patent.

Jennings was able to do this because he was born free in New York City. But for the great majority of black people in America before the Civil War, patents were unobtainable, as an enslaved person’s inventions legally belonged to his or her master.

According to The Inventive Spirit of African-Americans by Patricia Carter Sluby, Jennings started out as an apprentice to a prominent New York tailor. Later, he opened what would become a large and successful clothing shop in Lower Manhattan. He secured a patent for his “dry scouring” method of removing dirt and grease from clothing in 1821, when he was 29 years old. An item in the New York Gazette from March 13 of that year announces Jennings’ success in patenting a method of “Dry Scouring Clothes, and Woolen Fabrics in general, so that they keep their original shape, and have the polish and appearance of new.”

But we’ll never know exactly what the scouring method involved. The patent is one of the so-called “X-patents,” a group of 10,000 or so patents issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office between its creation in 1790 and 1836, when a fire began in Washington’s Blodget's Hotel, where the patents were being temporarily stored while a new facility was being built. There was a fire station next door to the facility, but it was winter and the firefighters’ leather hoses had cracked in the cold.

Before the fire, patents weren’t numbered, just catalogued by their name and issue date. After the fire, the Patent Office (as it was called then) began numbering patents. Any copies of the burned patents that were obtained from the inventors were given a number as well, ending in ‘X’ to mark them as part of the destroyed batch. As of 2004, about 2,800 of the X-patents have been recovered. Jennings’ is not one of them.

Sluby writes that Jennings’ was so proud of his patent letter, which was signed by Secretary of State—and later president—John Quincy Adams, he hung it in a gilded frame over his bed. Much of his apparently substantial earnings from the invention went towards the fight for abolition. He would go on to found or support a number of charities and legal aid societies, as well as Freedom’s Journal, the first black-owned newspaper in America, and the influential Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem.

All of Jennings’ children were educated and became successful in their careers and prominent in the abolition movement. His daughter Elizabeth, a schoolteacher, rose to national attention in 1854 when she boarded a whites-only horse-drawn streetcar in New York and refused to get off, hanging on to the window frame when the conductor tried to toss her out. A letter she wrote about the incident was published in several abolitionist papers, and her father hired a lawyer to fight the streetcar company. The case was successful; the judge ruled that it was unlawful to eject black people from public transportation so long as they were “sober, well behaved, and free from disease.” The lawyer was a young Chester A. Arthur, who would go on to become president in 1881.

Though free black Americans like Jennings were free to patent their inventions, in practice obtaining a patent was difficult and expensive. Some black inventors hid their race to avoid discrimination, even though the language of patent law was officially color-blind. Others “used their white partners as proxies,” writes Brian L. Frye, a professor at the University of Kentucky’s College of Law, in his article Invention of a Slave. This makes it difficult to know how many African-Americans were actually involved in early patents.

If a white person infringed on a black inventor’s patent, it would have been difficult to fight back, says Petra Moser, a professor of economics at New York University’s Stern School of Business.

“If the legal system was biased against black inventors, they wouldn’t have been able to defend their patents,” she says. The white infringer would have been believed. “Also, you need capital to defend your patent, and black inventors generally had less access to capital.”

It’s likely that some slave owners secretly patented their slaves’ inventions, Frye writes. At least two slave owners applied for patents for their slaves’ inventions, but were denied because no one could take the patent oath—the enslaved inventor was not eligible to hold a patent, and the owner was not the inventor.

Despite these barriers, African-Americans, both enslaved and free, invented an enormous number of technologies, from steamboat propellers to bedsteads to cotton scrapers. Some made money without patents. Others had their earnings exploited.

To this day, there’s a so-called “patent gap” between whites and minorities. Half as many African-American and Hispanic college graduates hold patents compared to whites with the same level of education. There are likely a number of reasons for this, from unequal education to income inequality to lesser access to capital, but what’s clear is that the gap is a loss for all of society.

“Invention requires a rare set of talents, let’s call them creativity, intelligence, and resilience,” Moser says. When you ignore the entire pool of non-white, non-male inventors, it's “hugely wasteful, to say the least.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)