Five Paralyzed Men Move Their Legs Again in a UCLA Study

As electrodes on the skin stimulated their spines, the study participants made “step-like” motions

The five men had each been paralyzed below the waist for at least two years. Some had suffered sports injuries; others had been in car accidents. Their legs were completely motionless, unresponsive to any internal or external stimuli.

But, during a groundbreaking new study conducted at UCLA, all five men moved their legs with the aid of transcutaneous stimulation, or the application of electrodes to the skin. It’s the first time such results have been achieved without surgery to implant electrodes beneath the skin.

"Until a year ago, if you had a spinal cord injury and you were completely paralyzed, you had no hope of recovery," says Roderic Pettigrew, director of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering at the National Institutes of Health, which helped fund the research. "That is no longer the case."

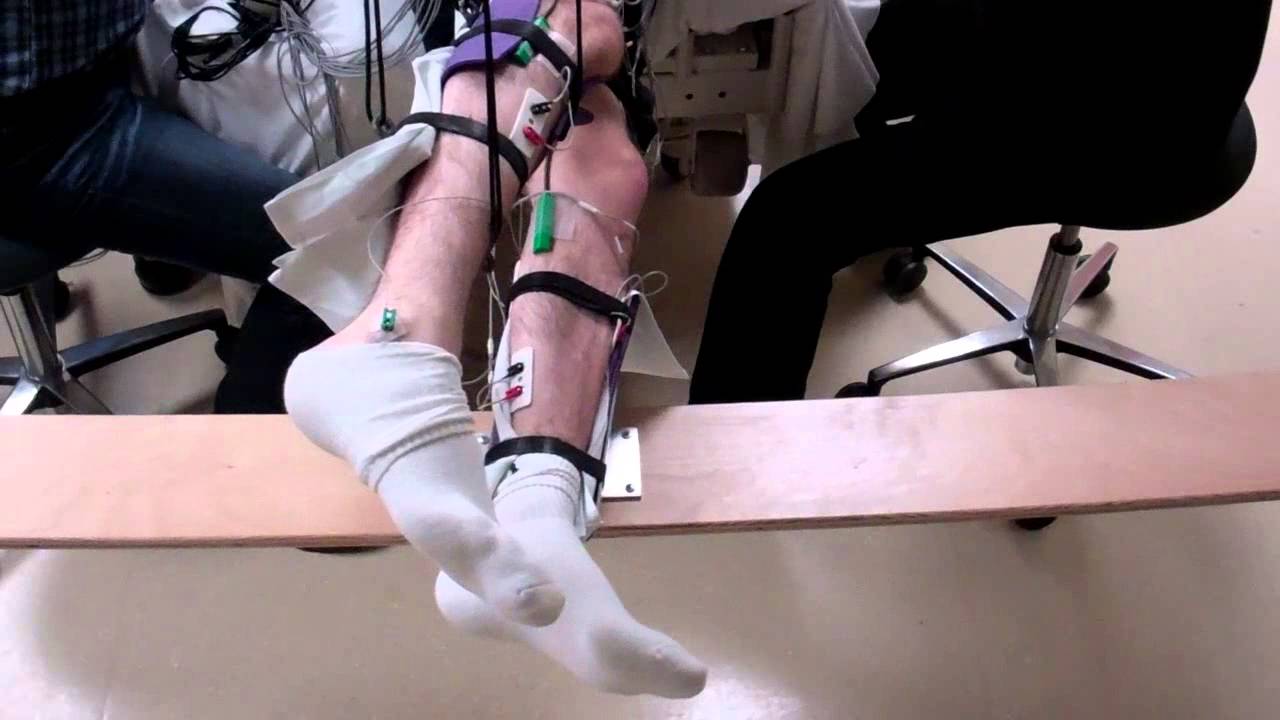

Over the course of 18 weeks, the five men in the study had weekly treatments. Doctors placed electrodes on the participants' lower backs and near their tailbones. Then, for 45 minutes, the men were suspended by braces from the ceiling, to take the weight off their legs, while electrical currents stimulated their spines. The stimulation produced a “step-like” motion, like walking on air.

“[Transcutaneous stimulation] permits us to stimulate the spinal cord in a manner that can activate circuits that reconnect the brain to the neurons that control muscles,” says V. Reggie Edgerton, senior author of the research and a UCLA distinguished professor of integrative biology and physiology, neurobiology and neurosurgery.

Previous studies looked at what’s known as epidural stimulation, where patients have electrodes surgically implanted in their spinal cords. Those studies showed great promise—subjects with the implants were able to voluntarily move their legs. But epidural stimulation is invasive, and it’s difficult to modify the electrodes once they’re implanted. With transcutaneous stimulation, the electrodes can be moved around as needed. The treatment is also "simpler to do, cheaper to do and easier to do," Pettigrew says. Researchers say the stimulation methods could eventually be used together to optimize treatment.

Conventional wisdom in paralysis research has long been that neurological circuits are completely dead. But since the test subjects recovered motion so quickly, it’s likely the circuits were simply “asleep.” This research is especially exciting, Edgerton says, because it suggests that the electrical current is helping reawaken these dormant circuits. The results of the research, funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation, the Walkabout Foundation and the Russian Scientific Fund, were reported in the Journal of Neurotrauma.

Researchers caution that the movement achieved in the study is not walking. The study subjects were tested while lying down, so no weight was put on their legs. “It will take considerably more improvement to reach a stage where complete weight bearing can be achieved,” Edgerton says.

Future studies will look at whether subjects can indeed learn to stand on their own with transcutaneous stimulation. The team also plans to study whether the treatment can help paralyzed people regain bodily functions often lost due to paralysis, such as sexual function and bladder and bowel control.

“We feel that we’re just scratching the surface, and it’s going to take a number of experiments over time,” Edgerton says.

Preliminary research suggests transcutaneous stimulation could also be useful for stroke victims and those with Parkinson’s disease. Studies are also beginning to investigate whether transcutaneous stimulation can help quadriplegics—people paralyzed in both their arms and their legs. This presents additional challenges, as quadriplegics' injuries often involve a greater degree of autonomic nervous system problems, as well as difficulty controlling breathing.

With proper funding, Edgerton says a transcutaneous stimulation device based on his team's research could be widely available in as little as two years. About 6 million Americans are affected by paralysis; 1.3 million of those have spinal cords injuries.

Russ Weitl, 45, was paralyzed below the waist in a rodeo accident in 2011. From the earliest days after his injury, he was determined to find some kind of treatment that worked. But a year of intensive physical therapy produced few results. Then, he joined the UCLA study.

"After not moving my legs for two years, to have control of my legs and be able to move them was unreal," he says.

Weitl even, jokingly, tried to kick one of the students assisting in the study. To his surprise, it almost worked. Though the study treatments didn't leave him with lasting movement once the electrodes were removed, he does have increased sensation.

"The important thing is that [the research] was a proof of concept," he says. "Now they know it works."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)