From 3-D Printed Gills to AI Dolphin Dictionaries, These Innovations Could Make Us More Like Aquaman

If you look beyond the movie, you can see how the underwater superhero’s signature powers translate in real tech

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/f6/a9f6c012-3978-4d68-975d-1a5852e0eda9/aquaman2.jpg)

Legendary under-the-sea superhero Aquaman is known for his super strength and speed, telepathic communication with animals, and ability to withstand the ocean depths then return to land with ease. In theaters now, the latest cinematic installment of the DC Universe, Aquaman, promises action-packed excitement, featuring a battle between the heir to Atlantis and his half-brother to prevent war with citizens living on land.

The ocean is Earth’s last frontier, and if Aquaman were real, there are certainly many ways in which he could help the science world. But in his absence, scientists in the real world have to get creative to achieve the feats only a fictional, conveniently-packaged half human-half Atlantean prince can.

Even then, we’ll really never be anywhere near conquering the lonely, vast ocean world—especially since so much of it is under threat. Or as Andrew David Thaler eloquently writes for the blog Southern Fried Science: “The ocean is not ours, and no matter how great our technology, we will never master it as we have mastered land, but Aquaman has.”

Super Sea-Faring Speed and Strength

The fastest speed Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps can reach is about 6 miles per hour. Compare that to some of the speedier swimmers of the sea, like dolphins, which can reach nearly 33 miles per hour, and you’re probably, understandably, unimpressed. Aquaman can allegedly swim faster than a shark, which max out at around 25 miles per hour, but other figures clock the fictional superhero at 175 miles per hour under water.

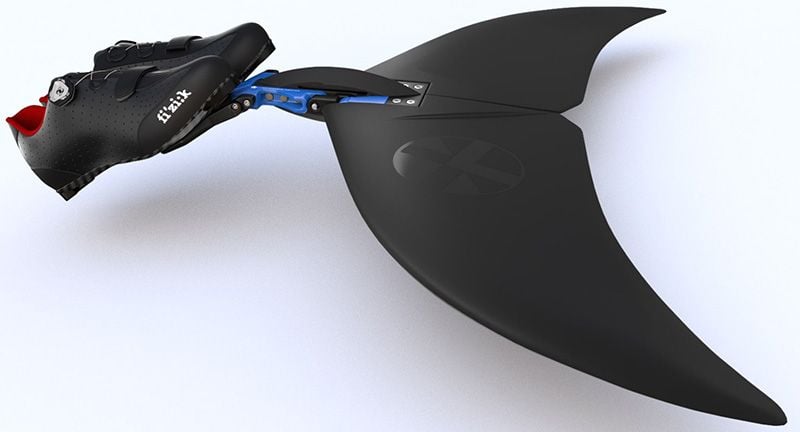

Scientists have tried to create devices to help divers swim faster; however, there’s a lot of risk to calculate. Dolphins actually avoid swimming faster because it would probably start to hurt, reports Catherine Brahic for New Scientist. Researchers have modeled a flexible carbon fiber and fiberglass fin, the Lunocet, after a dolphin tail, and swimmers can allegedly reach up to 8 miles per hour using the device, reports Julian Smith for Scientific American. Though Lunocet inventor Ted Ciamillo has said he has no interest in patenting the device, others have sought to patent similar fin-spired swimming tools.

"If you're taking ideas from nature," he told Smith at Scientific American in 2009, "how can you then go to the patent office and say these are mine?"

Surviving the Depths

Aquaman might be able to go right from land to water, dive down deep, shoot back up like a torpedo, do a giant leap into the air and repeat the whole schtick over again, but for humans and other marine life, it’s not that simple.

In order for humans to overcome the depths, they need air tanks. However, even with air tanks, there are risks, mainly in the form of the bends, also called decompression sickness. The bends occurs because nitrogen content in a diver’s air tank increases as the diver descends and the nitrogen naturally enters the diver’s system as they breathe. If the diver ascends to the surface too quickly, the bubbles of nitrogen in their body will burst—sort of like what happens when you open a bottle of soda that’s been shaken. Even some of nature’s best marine divers, sperm whales, aren’t immune to the bends and sometimes nitrogen build-up can damage their bones and organs, writes Lonny Lippett for the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Oceanus magazine.

Air tanks are still the major go-to tech for deep dives, but that doesn’t mean inventors aren’t getting innovative with underwater breathing mechanisms.

A few years ago a team from Denmark created a crystalline material that is highly concentrated with oxygen and can even absorb oxygen from water, reports Michael Byrne for Motherboard. The team initially claimed a single spoonful could suck the oxygen from a room, but later found it would take more like a five-gallon bucket full of the stuff. One day, with significant improvement, the material might be used in devices that would help divers breathe underwater, although it is not yet possible, writes David Mikkelson for Snopes. The group, fittingly, dubbed the substance Aquaman Crystal.

Just this September, CNN’s Ana Rosado reported on an idea that could have originated in Atlantis: a dystopian-inspired set of artificial gills. Designer and materials scientist Jun Kamei from the Royal College of London envisioned the gills as a means for humans, facing rising seas, to one day live underwater. (Although, Bethany Brookshire explains for Science News For Students why that won’t be happening anytime soon.) His 3D-printed design is inspired by insects that trap air in their exoskeletons to breathe underwater. For the most part, Kamei’s tech is still hypothetical—he doesn’t have a prototype. Although he has applied for a patent for the porous, water-repellent, oxygen-absorbing material he created, reports Dyllan Furness for Digital Trends.

While Atlantis is fictional, there are plenty of submerged artifacts and undersea archeological endeavors of interest to researchers. But, when it comes to exploring the depths, humans are better off relying on robots to reach the ocean’s nooks and crannies. For example, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) helped University of Michigan scientists study a sunken dry-land corridor in Lake Huron that was used by caribou hunters nearly 9,000 years ago.

Talk to the Animals

Aquaman’s most unique claim to fame is arguably his ability to talk to animals, mostly marine life. Communication with animals is often a prop in all sorts of magical, fictional worlds. Researchers are always studying how different species of primates, birds, bats and dolphins learn language and communicate.

Dolphins may actually prove to be one of the easiest animals to translate, with some researchers estimating that we’ll be able to understand the beasts using artificial intelligence by 2021, reports Karla Lant for Futurism. A Swedish language technology company called Gavagai AB initially used its AI to conquer 40 human languages, before announcing in 2017 that they’re taking their tech to the animal kingdom. The startup working with a wildlife park to “compile a dictionary of dolphin language,” reports Lant.

That’s not the first time humans have used computers to chat with the intelligent porpoises—in fact, Disney even threw their hat in the ring, receiving a patent in the 1990s. Researchers at the company proposed a keyboard with pictures on each key. The keys produce sounds that, hypothetically, both humans and dolphins would understand.

Marine biologist Denise Herzing and her team at The Wild Dolphin Project have been leaders in the field for quite some time. They created the Cetacean Hearing and Telemetry (CHAT) computerized vest to see if it was possible to detect dolphin calls and translate them to English. The device emits a sound that was taught to the pod of dolphins near the Bahamas that Herzing has studied for decades. What does that sound mean? Sargassum, a type of seaweed that divers often use as a toy when playing with dolphins. In 2014, they finally caught a dolphin making the sargassum sounds and CHAT translated it back to English, reports Tuan C. Nyugen for Smithsonian.com. If anything, the project illustrates how smart dolphins are to learn how to communicate with humans in order to get what they want. However, as Herzing tells Nyugen, we don’t exactly know what dolphins say to each other—and that’s okay. Interspecies communication is more the point.

So why might we need it? For starters, the U.S. Navy trains dolphins to search for sea mines, reports Kyle Mizokami for Popular Mechanics.

And who knows what marine life would actually have to say to humans. So much of the sea world is under threat by human hand, including things like warming waters, rising sea level, microplastics, trash, oil drilling, deep sea mining and more.

If Aquaman really could listen to ocean life, he’d probably get an earful.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)