From the Family Station Wagon to the Apollo Lunar Rover, My Dad’s Engineering Talent Had No Limits

Stricken with polio as an adult, he retired from the military and joined NASA’s ingenious design team

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/0f/ea0ffd60-54c9-4825-9495-a250f414b8ea/ford_station_wagon.jpg)

The lunar rover may not have roamed the moon’s surface on the day Apollo 11 made history, but its design had already crystallized by the time Neil Armstrong planted his feet in the Sea of Tranquility.

On July 20, 1969, our family gathered around the TV in our northern Virginia living room to watch the impossible happen. As an eight-year-old I had questions: Would a man really walk on the Man in the Moon? Quietly my father pondered his own question of whether he'd win a bet with NASA’s director.

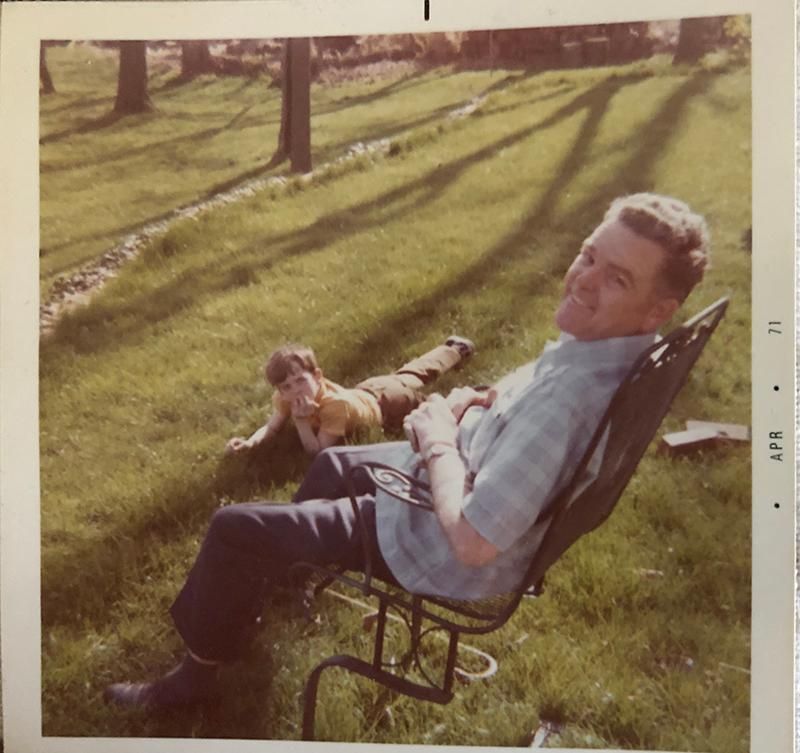

For me, Apollo is the story of that mid-level engineer behind the lunar rover, William Taylor. An army engineer felled by polio in his twenties, my father returned to work for the government after years of grueling recovery and physical therapy. For five years at NASA, he led projects to track Soviet space plans, survey the moon's surface before landing, and put the rover on its axles.

My father reported to NASA headquarters in May 1962. His shift from army engineering to the space program under NASA director James Webb was in some ways a leap. “There’s always risk when you take on something new like that,” he would say later.

Nearly a decade before, he’d been a 28-year-old army engineer stationed in Fort Belvoir, Virginia, with a wife and three small children when one day he woke up feeling achy with a pounding headache. My mother went with him to the hospital, where the medic who evaluated him wrote, “Spinal tap; rule out polio.” But, in fact, the test confirmed my father was in the last wave of polio cases before the vaccine became available. He spent a year in an iron-lung ventilator at Walter Reed, with a few snapshots of my mother and the kids taped inside the machine casing, inches from his face. My mother drove across Washington every day to visit him and boost his spirits, but the doctors doubted he would ever walk again.

After being retired from the military with a designation of 100 percent disability, he spent many months in physical and occupational rehab. That included a stint at Warm Springs, the post-polio treatment center in Georgia started by Franklin Roosevelt. In 1957, he returned to work as a civilian engineer with the Army.

“I had learned many tricks of the trade in working around the after-effects of polio,” he wrote in a memoir. He could walk with a cane, and a cleverly designed hand-splint kept his useless left arm close to his side.

Not being able to drive remained a big frustration. He bridled at being chauffeured around, but without use of his left arm or leg, driving was impossible. The introduction of automatic transmission in the late 1950s helped, but handling a steering wheel was still out of the question.

My father got an idea and found a machine shop on Route 1 just south of Alexandria with a mechanic open to innovation. To make our Ford station wagon steerable with one hand, they adapted a hydraulic rig designed for use in aircraft. They combined that with a pair of levers like the ones used to steer a tank. The mechanic built the levers and installed the rig in the hydraulic steering system of our family’s station wagon. It worked! After a few test drives with my mother in a school parking lot, my father passed his driver’s license exam.

“A major release from the ‘prison’ of my almost muscle-less body was relearning to drive,” he wrote.

My father’s military experience with satellites to map a geodetic survey of the Earth’s surface (initially for locating Soviet missile sites) would turn out to be useful for the moon. Geodesy—the science of accurately assessing the moon’s precise shape and properties—could help astronauts understand where to stick a landing, and what to expect when they started walking around.

That autumn of 1962, my father’s first boss at NASA, Joseph Shea, promoted him to assistant director for Engineering Studies. This involved frequent trips to NASA labs across the country, coordinating engineering teams that made equipment for the manned space flights. Thanks to his physical and occupational therapists, my father’s condition had stabilized and he had tools to help him navigate Earth’s gravity with the limitations imposed by polio.

Automotive technology had evolved to help him out. By the early 1960s, power steering was an option on U.S.-made cars.

“By the time I started traveling frequently for NASA, I could rent a car at my destination as long as it had automatic transmission and power steering,” he wrote. I don’t know that he ever discussed his physical condition or how he navigated limitations with his NASA supervisors. Those were the days before the Americans with Disabilities Act opened up such conversations.

Space Race Intelligence

“The race to the moon in the 1960s was, in fact, a real race, motivated by the Cold War and sustained by politics,” Charles Fishman writes in his new book One Giant Leap. This being the Cold War, NASA teamed with the CIA to gauge the competition. What was the Soviet plan for manned lunar exploration? Would they reach the moon before the U.S.? After Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space in April 1961, Americans knew better than to underestimate Soviet capability.

The main mystery was whether the Russians were working toward a manned lunar landing or an unmanned probe.

NASA’s Shea conferred with the CIA’s deputy director for science and technology and put together a small team of engineers from both agencies to study all the data on the secretive Soviet space program. Shea asked my father to head that team alongside his other duties. For several months he spent half his time commuting to the CIA's Langley headquarters in the wooded suburb of McLean, Virginia.

“Our group was compartmentalized in windowless offices,” he wrote, “a different experience for the more freewheeling NASA members of our team.” Working with “tight-lipped CIA comrades,” the team pored over satellite photos, telemetry data and cables about Vostok, the Soviet spacecraft. Working backwards from the images and descriptions, they “reverse engineered” the insides of the Soviet rockets and what made them tick.

The process was like engineering in the dark, and the team didn’t always trust their data. At one point their analysis suggested the Russians were designing an odd spherical craft. The NASA engineers dismissed the crude design. Then the Soviets unveiled the sphere at the 1965 Paris Air Show.

That year, the team reported, “Soviet launchings have sharply increased in the past year.” They predicted the Soviets would probably launch a manned space station by 1968 but a manned lunar landing by 1969 was not a Soviet priority. The CIA continued assessing the race long after my father left NASA in 1967. A month before the Apollo 11 launch they reported a Soviet manned lunar program was likely, “possibly including establishment of a lunar base,” but not until the mid-1970s.

Rolling on the Moon

My dad asked to return full-time to the Apollo program in 1964. (“Spook work is interesting and sometimes exciting, but being a professional spook is not my cup of tea,” he conceded in his memoir. He’d rather help build “something useful for people.”) He came back to the Apollo Applications Program, designing missions and equipment for extending the range of moon landings beyond a one-day visit and walking radius. One project he returned to was the moon rover.

By then he was working for Apollo manned space director George Mueller. Mueller was a workaholic like Webb. According to Webb’s biographer W. Henry Lambright, Mueller “labored seven days a week and expected others to do so, scheduling important meetings on Sundays and holidays… and seldom worrying if his decisions or manner of making them ruffled the feathers of subordinates.”

Mueller proved a master of timing decisions. From him my father learned not to make a choice a minute before you had to, “and in the meantime, explore all possible options in as excruciating a level of detail as time permits.” In the atmosphere of the space race, Mueller excelled at that fine-tuned timing. My father believed that Mueller “never got the credit he deserved as one of the most influential leaders in our fabulously successful manned lunar landing program.”

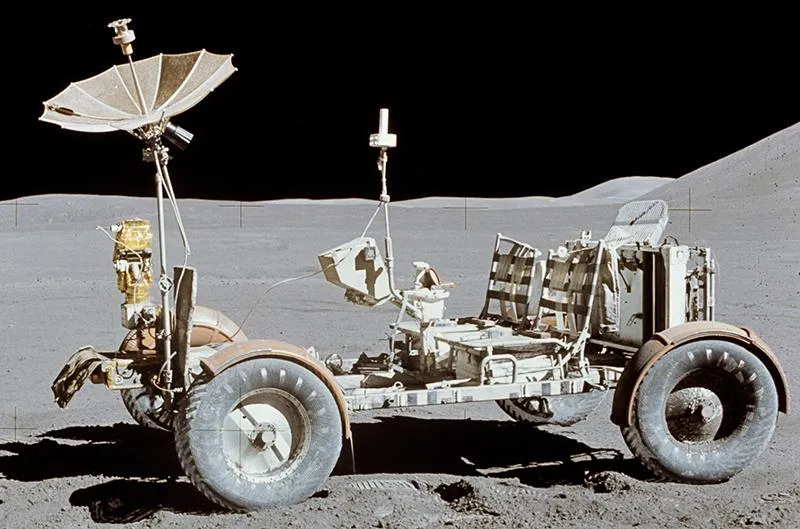

The solar-electric jeep that became the moon rover could be folded up and strapped to the landing module. Already deep in the pipeline by Apollo 11, it would join the moon mission for Apollo 15.

I like to think its design was informed in part by my father’s experience retooling our station wagon. In any case, the rover team, he wrote, “never dreamed, while they were in school, that they would play key roles in such a grand adventure.”

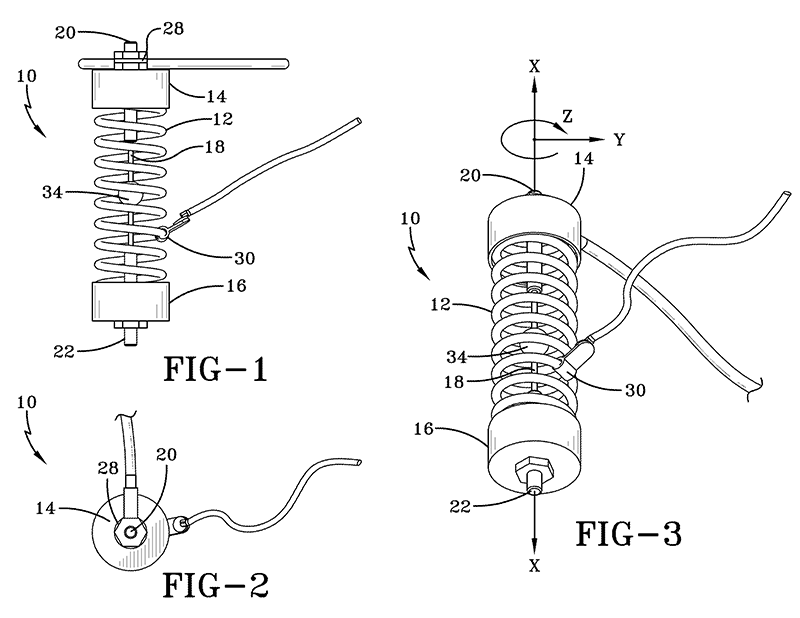

The moon rover led eventually to two Mars rovers and Curiosity’s long journey on the red planet. (Cue the Beatles’ “Across the Universe.”) Here on Earth the rover yielded, alongside other NASA patents, patent number 7,968,812 for a flexible universal joint that wouldn't twist and lock-up on the moon’s rocky terrain.

A Wager

Back in the thick of 1967, though, nothing was certain. NASA was herding plans and the budget for the rover through congressional approval. The NASA budget was by then politically unpopular.

At one internal briefing amid those budget fights, a weary Webb asked my father how confident he was that the moon landing would happen before the end of the decade. Six years on, Webb well knew Apollo’s public support had eroded since the day he supported Kennedy’s pledge.

My father did not hedge. “I told Mr. Webb I'd bet a bottle of good scotch on it,” he recalled later. “He said I had a bet.”

That July afternoon when I was eight and we watched Armstrong drop from the ladder to the ground, I couldn’t make out what he said through the static. But we were all moved. My father lived until age 86, and the moment was a highlight in his professional life. “I won the bet,” he joked years later, “but I'm still waiting for the scotch.”