“Hi, Joel? It’s Marty Cooper.”

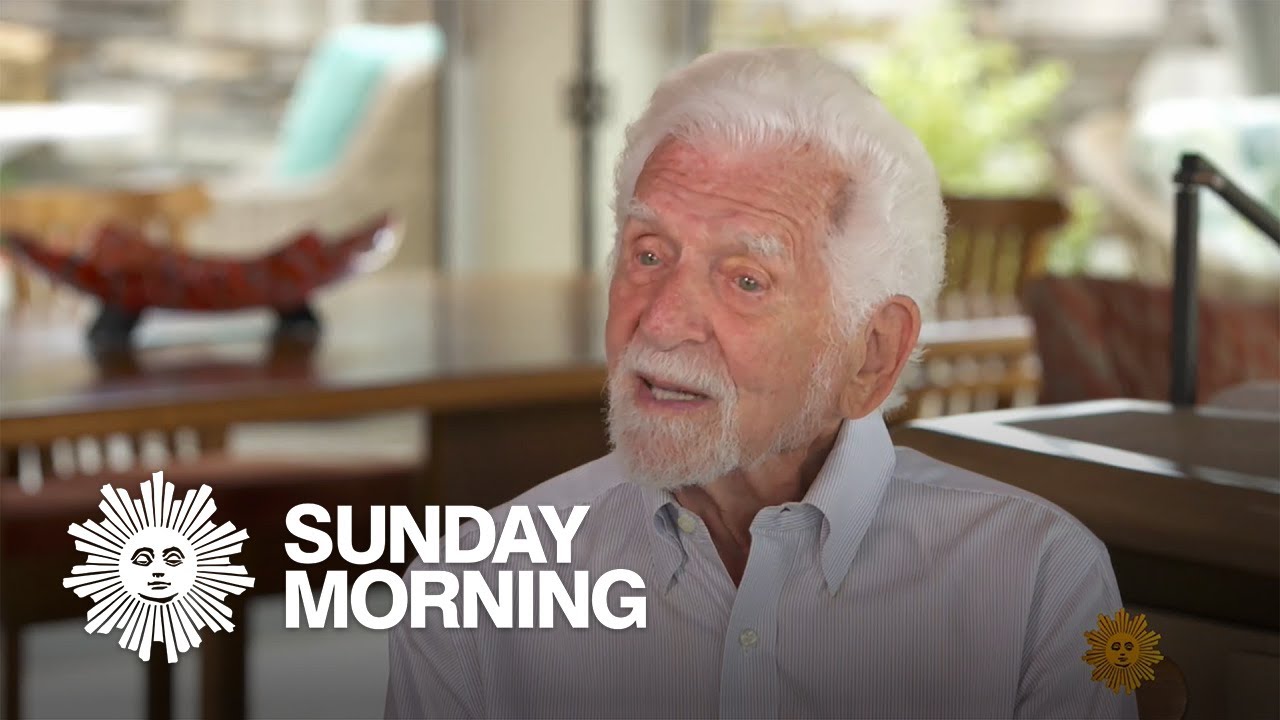

Engineer Martin Cooper cradled a bulky object to his ear, listening. The gray device had two rows of numbered buttons between the ear and mouthpiece. An antenna poked from the top, reaching skyward to pick up invisible signals from the city’s jangling atmosphere. Next to the sidewalk, cars and taxis zipped down Sixth Avenue through midtown Manhattan. It was April 3, 1973, and Cooper had just placed the world’s first cellphone call.

Cooper, who worked for Motorola, had just stepped out of the Hilton Midtown where he would soon officially demonstrate the wireless personal cellphone his team had developed. When a journalist approached him during the pre-event mingling, Cooper was struck by the impulse to manufacture a newsworthy anecdote—and decided to call Joel Engel, who led AT&T’s rival cellphone program. “I decided ‘Well, why don’t we give him a real demonstration?’” Cooper recalled years later. “And that’s exactly what we did.”

To Cooper’s relief, he soon heard Engel’s voice on the line: “Hi, Marty.” Thrilled by his victory, Cooper couldn’t help crowing. “I’m calling you from a cellphone. But a real cellphone! Personal, hand-held, portable cellphone.” There was silence at the other end, and in Cooper’s telling, Engel would later claim not to remember the call at all.

Today, there are more cellphones than people on Earth. Cooper’s DynaTAC cellphone—which turns 50 this year—transformed the way we keep in touch, reshaped the etiquette of public space and began the slow death of the wired phone system.

But before cellphones were a fixture in our daily lives, they were the stuff of science fiction. How did a device that once appeared in space odysseys and sci-fi magazines become so commonplace? And what’s next?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0d/0c/0d0c680b-418f-4ce0-8e93-a2bf78bf47fb/gettyimages-1278980903.jpg)

The creation of the cellphone

Though Cooper is hailed as the inventor of the modern cellphone, the device’s history began much earlier.

“Whoever was first, there’s always somebody who was more first,” Hal Wallace, curator of electricity collections at the National Museum of American History (NMAH), explains. The phrase, known as the Sivowitch Law of Firsts, came from Elliot Sivowitch, the late television and radio historian who worked as a curator at the museum for some 40 years.

This is certainly true for the history of cellphones. Wallace traces cellphones back to World War II battlefields, where soldiers relied on short-range mobile radios to relay messages from the trenches. This walkie-talkie technology evolved further with the arrival of the transistor, a small device that amplifies electrical signals that are broadcast through a speaker, in 1948. “If you can get rid of the vacuum tubes—because they’re energy hogs—transistors don’t need much energy,” Wallace explains. The 1950s brought transistor radios, which were powered by relatively long-lasting 9-volt batteries.

In the midst of this technological shift, car phones arrived on the scene. The original car phones weighed 80 pounds and connected users with a switchboard operator, who could only access the service in or near major cities. By the 1960s, car phones had shrunk to half the size. The 30- to 40-pound devices were mounted in the trunk of the car. Cabling ran through the length of the vehicle, connecting to a headset hooked up next to the driver’s seat, and an antenna beamed and received the signals that enabled communication. Today, the NMAH has several examples of General Electric car phones from 1969. “I love bringing them out of storage,” Wallace says, “because kids’ eyes just get real big when I tell them, ‘This is a portable telephone.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3e/fe/3efeb18c-6651-4048-a1af-272f699fa31c/gettyimages-3303642.jpg)

These early car phones weren’t widely available; just 5,000 Americans had them by 1948. Although the technology became affordable and widely accessible by the 1960s, its user base was intentionally limited. The Federal Communications Commission required would-be users to obtain licenses to operate their car phones—and denied applicants who didn’t meet its stringent requirements.

“Because of the technology and the problem with radio frequency interference, you can only have a certain number of licenses in a major metropolitan area,” explains Wallace. The FCC’s carefully rationed licenses kept the phone lines clear for important figures, such as government officials, senior business executives and doctors who needed to respond to urgent calls. In 1983, Washington, D.C.’s mobile phone infrastructure was supported by a single transmitter, allowing “no more than two dozen users” to place calls at the same time.

But the modern cellphone has a distinct origin story—one that emerged in parallel to the car phone and hearkened back to the World War II mobile radios. In 1947, a Bell Laboratories engineer named Douglas H. Ring wrote a memo that sketched the basic functionality of the modern cellphone.

Ring imagined a system in which mobile phones functioned like radio transmitters and receivers. His concept improved upon longstanding radio technology by proposing geographic “cells” that served small, modular areas. By adding more nodes in the cellular network, Ring’s system would avoid becoming overloaded with users, keeping airwaves clear for an exponentially greater number of simultaneous conversations.

Like Ring’s, Cooper’s vision for a mobile phone was also built on radio. He began to work on Motorola’s cellphone in earnest shortly after AT&T announced a new car phone. “We believed people didn’t want to talk to cars and that people wanted to talk to other people,” Cooper told the BBC in 2003. “The only way we at Motorola, this little company, could prove this to the world was to actually show we could build a cellular telephone, a personal telephone.”

In Cooper’s mind, cellphones would be truly personal devices, with phone numbers representing a direct connection to an individual, rather than a car, a desk or a static location. Within three months, Cooper, designer Rudy Krolopp and a team of engineers had developed a working prototype.

The Motorola DynaTAC—short for Dynamic Adaptive Total Area Coverage—was the official name for what many dubbed “the Brick.” It contained 30 circuit boards, yet it weighed just 2.5 pounds and measured 9 inches tall. It required 10 hours to fully charge, powering 35 minutes of conversation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/10/53/10533451-ad28-458e-b346-82479dc94500/gettyimages-1249917046.jpg)

“Today, we’d kind of sneer at it because of its size and bulk,” says Wallace. “But compared to something that requires 50 pounds’ worth of equipment mounted in your car, it was actually a pretty big deal.”

A decade later, in 1983, Motorola’s cellphone was finally available for commercial service. Users paid $3,500, the equivalent of nearly $10,600 in 2023. By 1990, one million Americans had taken the plunge.

Today, the vast majority of American adults own a cellphone—97 percent, according to the most recent data from the Pew Research Center. Statista, a market and consumer data platform, predicts that more than 18 billion mobile devices will be in use globally by 2025.

The cellphone as culture

Long before engineers and scientists built the ever-shrinking technologies that made cellphones possible, writers and artists vividly imagined the future.

The Motorola design built on not only a real-world foundation of radio technology, but also the boundless realm of science fiction. Cooper was fascinated by a radio wristwatch used in the comic book adventures of detective Dick Tracy. In the 1990s, Motorola’s first flip phone drew inspiration from “Star Trek” communicators.

Lisa Yaszek is a professor of science fiction studies at Georgia Tech—and a lifelong fan of the genre. “Communications technologies have always been part of science fiction as a modern genre,” Yaszek says, starting in the 1800s with novels including Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas and continuing in the American magazines such as Astounding Stories and Fantasy that ushered in the 20th century.

Yaszek finds that references to cellphone-like devices proliferated during the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, forming a symbiotic relationship with real-world technology. While scientists and engineers achieved increasingly impressive feats of miniaturization, science fiction writers imagined all the ways cellphones might become woven into modern life. From “pocketphones” in Robert A. Heinlein’s 1953 novella collection Assignment in Eternity to caller contact lists and voicemail in Frederik Pohl’s 1966 novel The Age of the Pussyfoot, writers predicted—or possibly informed—details of the cellphone’s eventual arc with eerie precision. Plus, cellphones solved practical problems writers faced. Communication devices collapsed interstellar distances, allowing writers to immediately drive their plots forward, no monthslong voyages or cryogenic chambers required.

For some, cellphones and radios were part of a utopian vision of the future. “Women have always been right at the center of new communications technology stories,” Yaszek notes. As women took on jobs as switchboard operators during the 1920s, telephones took on a distinctly feminine gender in the public imagination. Science fiction authors, in turn, wrote works almost prophetic in their visions of the future. Clare Winger Harris’ short story “The Fate of the Poseidonia” imagined what Yaszek calls “interplanetary Zoom” in 1927. Two years later, Lilith Lorraine—who was herself a pioneering radio educator—published The Brain of the Planet, in which radio waves could eradicate feelings of greed and fear to create a utopian society.

Black writers, too, were at the forefront of imagining the powerful ways technology could bring communities together. George Schuyler’s serialized Afrofuturist saga Black Empire first proposed the fax machine—in 1938.

It’s a vision Cooper shared. “Wireless is freedom,” he once told a BBC News reporter. “It’s about being unleashed from the telephone cord and having the ability to be virtually anywhere when you want to be. That freedom is what cellular is all about. It pleases me no end to have had some small impact on people’s lives because these phones do make people’s lives better.”

For science fiction writers, embracing technology was also a savvy career move. Authors who dreamed of being published in Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories—the first magazine devoted solely to science fiction, which published from 1926 through 1980—knew that Gernsback himself was a pioneering radio and television broadcaster. “It’s no surprise his writers would want to get in his good graces by writing stories about new communications technologies,” Yaszek says.

Among the many midcentury writers who dreamed up cellphone-esque gadgets, some envisioned communications devices that doubled as fashion statements—a prediction that blossomed in the early 2000s. By 2002, the Brick’s bulky design had given way to slim phones like the T-Mobile Sidekick, which featured a full QWERTY keyboard, for instance. Motorola’s wafer-thin Razr, released in 2004, eventually came in more than ten colors, from baby blue to bubblegum pink. Blackberry devices gave off the impression that weighty business matters might interrupt at any moment. Haute couture designers including Prada, Versace and Armani all released collaborations with cellphone companies. Even ringtones could be customized; one of the most popular, “Crazy Frog,” grossed $40 million in ringtone downloads in 2004. Cellphones were more than just a practical tool—they were fashion accessories that put your taste and disposable income on display for all to see.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/31/dc/31dc0180-0df1-4398-bf2f-083646407fbf/gettyimages-143992904.jpg)

In a 2004 article for the New Atlantis, senior editor Christine Rosen documented the often irritating ways cellphones reshaped public space. Americans, she found, would rather go to the dentist than listen to a cellphone-wielding stranger drone loudly in public. Singles—particularly men—engaged in “hyperactive peacocking,” flexing both their wealth and their desirability by displaying their cellphones in public. Researchers found that some went so far as to carry fake cellphones to nightclubs.

A few years after Rosen’s article was published, the mobile phone’s trajectory changed once again. Throughout the ’90s, smartphone technology became gradually sleeker, starting with an IBM touchscreen phone in 1993. Inside smartphones, components became smaller and more powerful than ever, thanks to innovations such as integrated circuits and long-lasting lithium batteries. When the first iPhone was released in 2007—quickly followed by the first Android in 2008—the colorful array of RAZRs and Sidekicks were doomed to be replaced by uniformly sleek designs. While the first Android featured a slide-out keyboard similar to the Blackberry, Apple’s minimalist design and touchscreen would soon become the smartphone standard. In 2022, iPhones claimed 50 percent of U.S. market share, overtaking Androids for the first time. Today, two companies, Apple and Samsung, dominate, together manufacturing more than three-quarters of the smartphones Americans use.

For Wallace, the story of cellphones is one of steady convergence. While the DynaTAC freed users to place calls on the go, smartphones are much more than communication devices. They’re flashlights and cameras, video recorders and internet portals, with dozens of components and a nearly limitless variety of apps packed into a single, convenient device. “At the moment, that’s what’s motivating my collecting in this area,” Wallace says. “It’s also making us at NMAH evaluate who should collect what. Should a smartphone be in the Electricity Collections because it’s a phone, or in Computers & Math because it’s really a miniature computer, or maybe in Photo History?”

The future of the cellphone

Since 1973, cellphones have delivered on sci-fi’s imaginings and then some. What, I wondered, does science fiction suggest might come next? When I ask Yaszek, she answers without hesitation: “Fungal-based communication systems.”

Scientists have long known that plants can communicate through an “internet of fungus,” a concept science fiction writers have eagerly explored. Yaszek traces sci-fi’s fascination with fungi all the way back to 1918, when Francis Stevens wrote a story about a sentient island that floated freely on a mass of tangled roots titled “Friend Island.” More recently, Tade Thompson’s Wormwood Trilogy posits anti-colonial resistance to a mind-controlling alien fungi that descends upon Nigeria. Beyond the page, fungi has also popped up on TV: On January 22, HBO’s adaptation of the video game The Last of Us broke a 50-year viewership record as fans tuned in to experience a terrifying vision of humanity ravaged by Cordyceps fungi.

At the University of the West of England’s Unconventional Computing Laboratory, the future is already here. Director Andrew Adamatzky has developed a method of inserting electrodes into mycelium, the root-like threads that form fungal networks (aka the “woodwide web”). He’s found that, like human neurons, mycelium displays recognizable spiking patterns and can form stronger conductivity over time, similar to the way memories and habits form in the brain.

[I’m obsessed with some of the images in the stories linked in the previous graf]

These discoveries have led to unconventional motherboards that feature blooms of oyster, enoki and caterpillar fungi. In 2020, Adamatzky was working on the European Union-funded FUNGAR project, a smart technology that would use fungal-based building materials to sense and react to environmental changes, triggering responses like light and temperature regulation. In a 2022 interview with Inverse, electronic engineer Martin Kaltenbrunner of Johannes Kepler University in Linz, Austria, confirmed that mushroom-based cellphones were not only feasible, but also would be biodegradable—a powerful way to reduce more than 51 million tons of e-waste generated annually.

“We never could have predicted what has happened to the technology over the years since we created that first cellphone,” Cooper once said.

Fifty years after the Motorola DynaTAC transformed communications technology, he’s still exactly right.

"Cellphone: Unseen Connections," a new exhibition exploring the technological, environmental and cultural impact of cellphones, opens at Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History on June 23, 2023.

:focal(1864x1812:1865x1813)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fd/21/fd21fb60-6cc4-4402-994a-8a0f749f4c31/gettyimages-1249917576.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michelle.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michelle.png)