With Google Maps, It’s Now Possible To Travel Through Time

We can all be Marty McFly thanks to a new tool in Google Street View that offers seven years of views from street corners around the globe

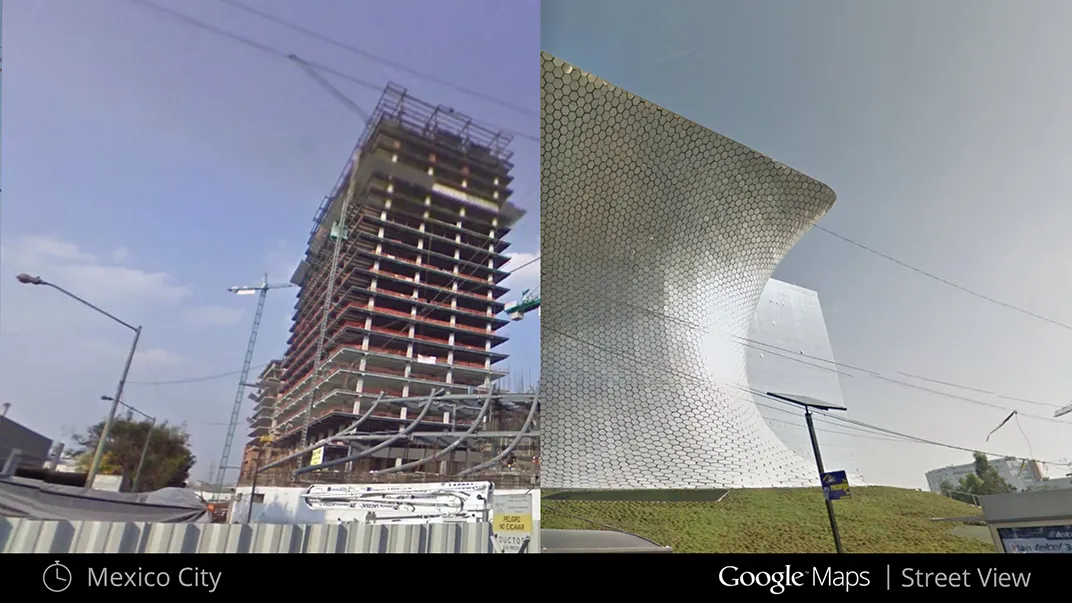

A lot can change in seven years: buildings rise and landscapes change. Whether you’re standing near the ocean in Japan or in the middle of Times Square, your view will likely be quite different in less than a decade.

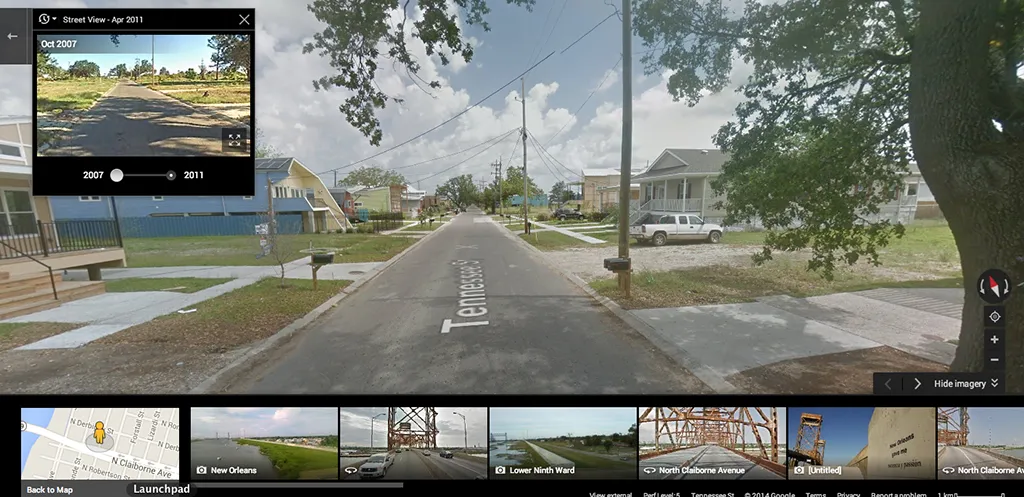

That’s the premise behind Google Maps’ newest time-lapse tool, launched today. Since it was released in 2007, Google Street View has allowed users to explore a given area from the perspective of walking along a sidewalk, but with the new tool, they’ll actually be able to see how the street and its surroundings have changed.

“Our mission in maps is to build a map that’s accurate, useful and comprehensive, and I think that being able to expose historic images that we’ve collected in the past helps us be able to meet this comprehensiveness aspect,” says Vinay Shet, the product manager of Google Street View.

The new time-travel function draws on image data captured by a fleet of Google Street View SUVs, snowmobiles, tricycles, and even a backpack, which for seven years have trekked across the globe with video cameras and GPS units to capture busy intersections and rolling hillsides across all seven continents. By selecting "street view" and clicking on a clock icon at the top of the screen, users can explore an area’s evolution as far back as Google’s photo-documentation can reach. The project pulls together years of Google Street View imagery, some of it previously unreleased, and took several months to complete. It marks the latest in a recent string of expansions in what users can see in street view, from the ruins of Angkor Wat to the Colorado River.

Users can travel back in time wherever street view is available around the world, and the project will continue to add to its collection of image data as years pass.

“In two years time 2007 will be vintage, so we hope that as time goes by this tool becomes more and more valuable to our users,” Shet says.

On some level the tool is similar to time-lapse videos, but it's not the same. The tool serves as an interactive visual archive that to date has only been available manually by sifting through old digital images, film strips and negatives.

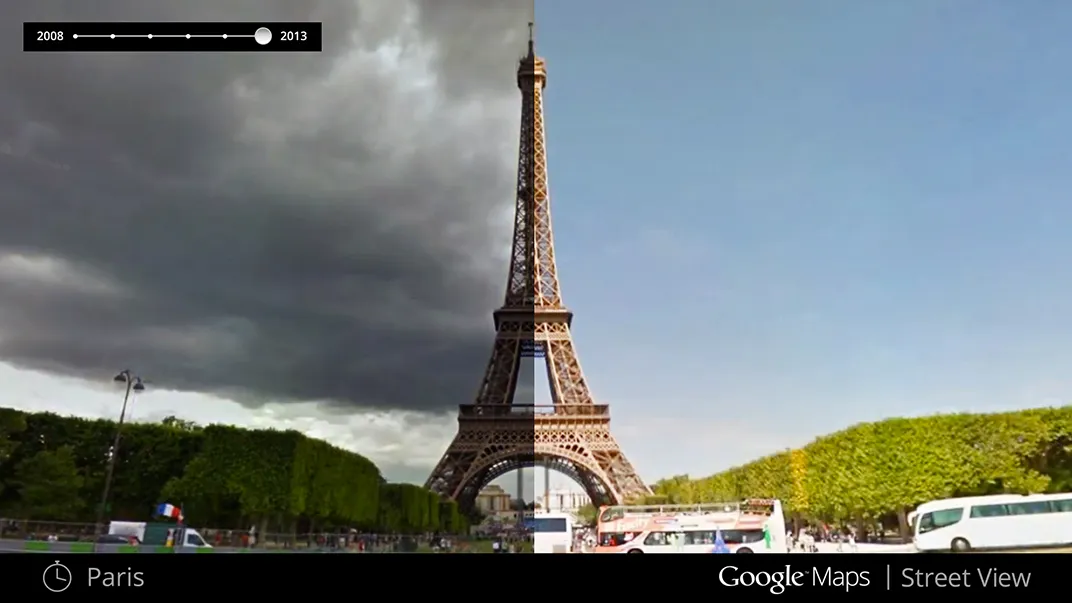

Before releasing the tool, Shet and his team did some exploring of their own with what the technology could offer. Some of the most common scenes to be viewed with the tool are ever-changing urban skylines around the world, including the rise of landmark buildings like the World Cup stadium in Rio de Janiero, the World Trade Center’s Freedom Tower in New York City, and the Marina Bay Sands hotel in Singapore.

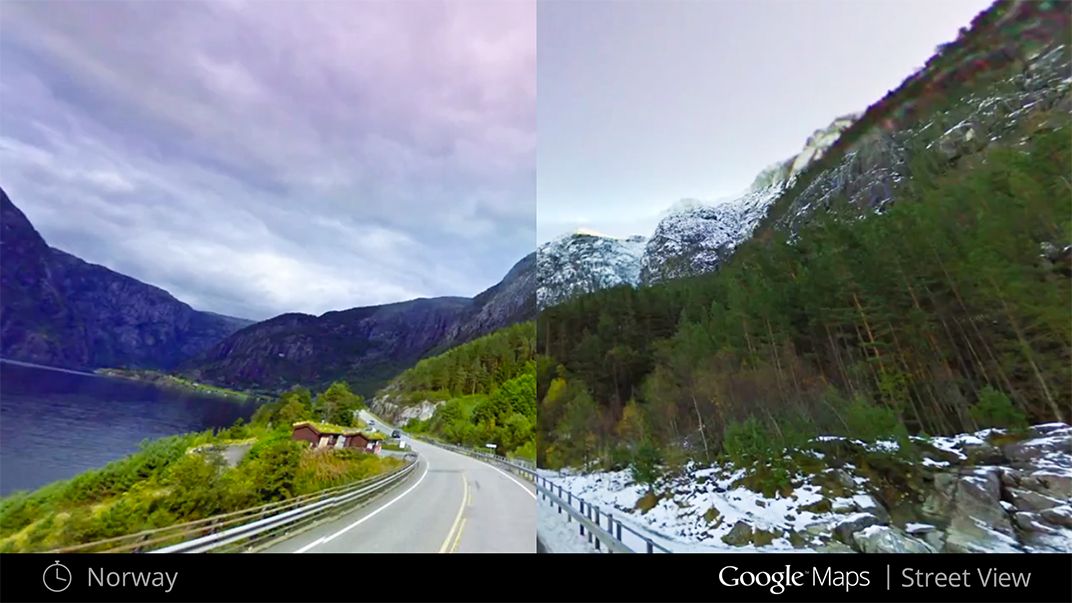

Users can also see changes in nature as the world shifts between seasons, a natural phenomenon that’s made time-lapse videos across the Internet forever popular. In Norway, for example, a mountain road goes from an idyllic summer scene to one blanketed with snow.

“It’s the same place but it looks dramatically different,” Shet says.

The tool also highlights areas hit by natural disasters in the last seven years, from the fallout and reconstruction of land along coastal Japan—ravaged by both an earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011—to the earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand that same year.

Interestingly, in Japan, the viewer gets the impression of physically moving horizontally when clicking between past and present. At first, developers thought they had taken footage from the wrong coordinates. “In reality, the ground had shifted by around 5 meters,” Shet says. “But you see that effect when you go across time, so I think that this a really powerful imaging tool that you have there.”

Beyond imagery highlighting the beauty and destruction of nature, the Google Street view imagery shows social change. Changing advertisements in Time Square reveal shifts in technology from flip phones to smart phones, while a street view of an urban building might show the artistic evolution of its graffiti.

Google's decision to make the images public opens them up to a wide array of possibilities. One could envision urban scientists looking at how a neighborhood has changed over the years, or criminal investigators reconstructing the appearance of an old crime scene. Whether those fields find the tool useful remains to be seen, but Shet is optimistic it will have applications beyond the initial wow-factor.

“Obviously, people can use it in whatever way they want. People are going to look at how things have changed in an interesting way and how humanity has kind of moved forward in different ways,” Shet says. “It’s going to be exciting to see what people find.”

So, go forth and virtually explore your neighborhood’s evolution over the last seven years—who knows what you might discover.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)