In Hawaii, Old Buses Are Being Turned Into Homeless Shelters

A group of architects envisions a rolling solution to the state’s homelessness problem

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/67/3567fa45-8242-4417-9ba3-26fc09883126/bus1.jpg)

When we think of Hawaii, most of us probably picture surfers, shaved ice and sleek beach resorts. But the 50th state has one of the highest rates of homelessness in America. Due in large part to high rent, displacement from development and income inequality, Hawaii has some 7,000 people without a roof over their heads.

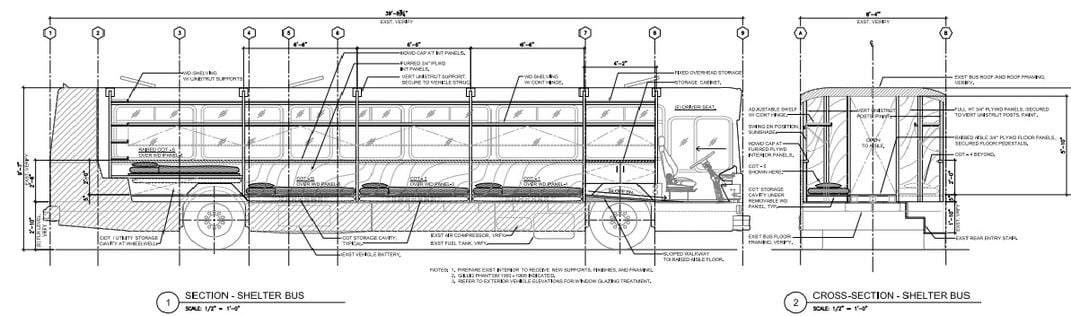

Now, architects at the Honolulu-based firm Group 70 International have come up with a creative response to the homelessness problem: turn a fleet of retired city buses into temporary mobile shelters.

“Homelessness is a growing epidemic,” says Ma Ry Kim, the architect at the helm of the project. “We’re in a desperate situation.”

Kim and her friend Jun Yang, executive director of Honolulu’s Office of Housing, came up with the idea after attending a disheartening meeting of Hawaii’s legislature. Homelessness was discussed but few solutions were offered.

“[Jun] just said, ‘I have this dream, there’s all these buses sitting at the depot, do you think there’s anything we can do with them?’” Kim recalls. “I just said ‘sure.’”

The buses, while still functional, have too high mileage for the city of Honolulu to use. The architects envision converting them into a variety of spaces to serve the needs of the homeless population. Some buses will be sleeping quarters, with origami-inspired beds that fold away when not in use. Others will be outfitted with showers to serve the homeless populations’ hygiene needs. The buses will be able to go to locations on the island of Oahu where they are most needed, either separately or as a fleet. The entire project is being done with donated materials, including the buses themselves, and volunteer manpower. Members of the U.S. Navy have pitched in, as have local builders and volunteers for Habitat for Humanity. The first two buses are scheduled to be finished by the end of the summer.

The blueprint for the shower-equipped hygiene bus comes from the San Francisco program Lava Mae, which put its first shower bus on the streets of the Mission District in July 2014. Kim hopes to “pay it forward” by sharing her group’s foldable sleeping bus designs with other cities.

“The next city can adopt it and add their piece or two,” Kim says. “There are retired buses everywhere. The missing part is the instruction manual on how to do this.”

The project comes on the heels of recent controversy about new laws preventing the homeless from sleeping in public. Proponents say the laws, which make it illegal to sit or sleep on Waikiki sidewalks, are a compassionate way of getting the homeless off the streets and into shelters. Critics say the laws are merely criminalizing homelessness and making life more difficult for Hawaii’s most disadvantaged population in order to make tourists feel more comfortable.

The needs of the homeless are varied. While a small percentage of the homeless are chronically on the streets, most are people experiencing difficult transitions—a loss of a house due to foreclosure, fleeing domestic violence, displacement by natural disaster. Increasingly, designers and architects are looking to fill these needs with creative design-based solutions.

In Hong Kong, the architecture and design group Affect-T created temporary bamboo dwellings for refugees and disaster victims. The dwellings are meant to sit inside warehouses or other sheltered spaces. Light and easy to transport and construct, the dwellings could be a model for temporary shelters anywhere in the world.

The Italian firm ZO-loft Architecture and Design built a prototype for a rolling shelter called the Wheely. The temporary abode looks like a large can lid, and opens on either side to unveil two polyester resin tents. The internal frame provides space for hanging belongings, and the tents, which stretch out like Slinky toys, can be closed at the end for privacy and protection from weather. Inventor Paul Elkin came up with a similar solution—a tiny shelter on wheels that unfolds to reveal a larger sleeping space.

But temporary shelters don’t solve the problem of chronic homelessness. It’s increasingly understood that simply giving homeless people homes—a philosophy called Housing First—is more effective than trying to deal with the underlying causes of their homelessness while they’re still living in shelters. Housing First is also cost effective, since people with homes end up needing fewer social supports and are less likely to end up in prisons or emergency rooms.

A number of cities are tapping into the mania for tiny houses as a more permanent partial solution. In Portland, Dignity Village is a permanent community of some 60 people living in 10-by-12-foot houses near the airport. The houses were built mostly with donated or salvaged materials, and residents share communal kitchens and bathrooms. The village was originally an illegal tent encampment, but the city granted the community land, which ensures houses are built to city code. Residents say the village grants them not just shelter and safety, but also privacy and autonomy. Unlike in homeless shelters, residents have a permanent spot and are allowed to live with partners and pets. Similar villages exist across the Pacific Northwest and California, with more springing up in other parts of the country.

With homelessness on the rise in America—a recent U.S. Conference of Mayors survey of 25 cities showed homelessness had increased in nearly half over the past year—we'll certainly be in need of more design-inspired solutions, tiny, rolling, and otherwise.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)