This High Schooler Invented Color-Changing Sutures to Detect Infection

After winning a state science fair and becoming a finalist in a national competition, Dasia Taylor now has her sights set on a patent

:focal(1357x414:1358x415)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/26/4a264c90-0536-4acc-9e2b-4b5a5dff696d/dasia_taylor.jpg)

Dasia Taylor has juiced about three dozen beets in the last 18 months. The root vegetables, she’s found, provide the perfect dye for her invention: suture thread that changes color, from bright red to dark purple, when a surgical wound becomes infected.

The 17-year-old student at Iowa City West High School in Iowa City, Iowa, began working on the project in October 2019, after her chemistry teacher shared information about state-wide science fairs with the class. As she developed her sutures, she nabbed awards at several regional science fairs, before advancing to the national stage. This January, Taylor was named one of 40 finalists in the Regeneron Science Talent Search, the country’s oldest and most prestigious science and math competition for high school seniors.

As any science fair veteran knows, at the core of a successful project is a problem in need of solving. Taylor had read about sutures coated with a conductive material that can sense the status of a wound by changes in electrical resistance, and relay that information to the smartphones or computers of patients and doctors. While these “smart” sutures could help in the United States, the expensive tool might be less applicable to people in developing countries, where internet access and mobile technology is sometimes lacking. And yet the need is there; on average, 11 percent of surgical wounds develop an infection in low- and middle-incoming countries, according to the World Health Organization, compared to between 2 and 4 percent of surgeries in the U.S.

Infections after Cesarean sections particularly caught Taylor’s attention. In some African nations, up to 20 percent of women who give birth by C-section then develop surgical site infections. Research has also shown that health centers in Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Burundi have similar or lower rates of infection, at between 2 and 10 percent, following C-sections than the U.S., where rates range from 8 to 10 percent.

But smartphone access is markedly different. A BBC survey published in 2016 found that in Sierra Leone, about 53 percent of people own mobile phones, and about three-quarters of those owned basic cell phones, not smartphones.

“I've done a lot of racial equity work in my community, I've been a guest speaker at several conferences,” says Taylor. “So when I was presented with this opportunity to do research, I couldn't help but go at it with an equity lens.”

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Taylor spent most of her time after school in the Black History Game Show, a club she’s been a member of since eighth grade, and attending weekly school board and district meetings to advocate for an anti-racist curriculum. For the four months leading up to her first regional science fair in February 2020, Taylor committed Friday afternoons to research under the guidance of her chemistry teacher, Carolyn Walling.

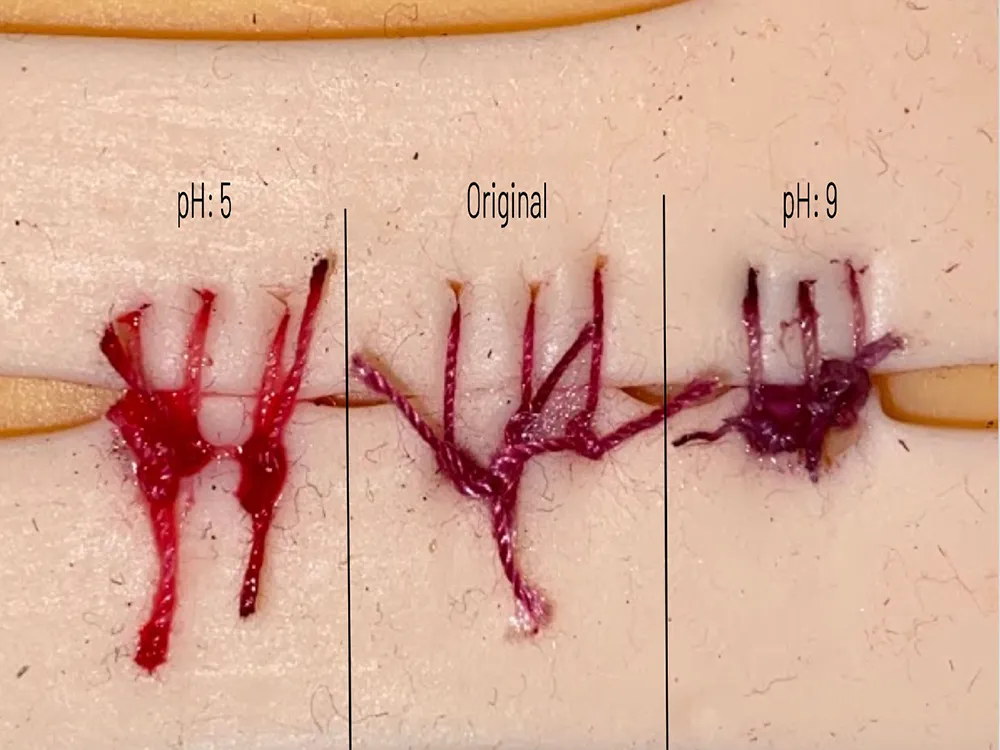

Healthy human skin is naturally acidic, with a pH around five. But when a wound becomes infected, its pH goes up to about nine. Changes in pH can be detected without electronics; many fruits and vegetables are natural indicators that change color at different pH levels.

“I found that beets changed color at the perfect pH point,” says Taylor. Bright red beet juice turns dark purple at a pH of nine. “That's perfect for an infected wound. And so, I was like, ‘Oh, okay. So beets is where it's at.’”

Next, Taylor had to find a suture thread that would hold onto the dye. She tested ten different materials, including standard suture thread, for how well they picked up and held the dye, whether the dye changed color when its pH changed, and how their thickness compared to standard suture thread. After her school transitioned to remote learning, she could spend four or five hours in the lab on an asynchronous lesson day, running experiments.

A cotton-polyester blend checked all the boxes. After five minutes under an infection-like pH, the cotton-polyester thread changes from bright red to dark purple. After three days, the purple fades to light gray.

Working with an eye on equity in global health, she hopes that the color-changing sutures will someday help patients detect surgical site infections as early as possible so that they can seek medical care when it has the most impact. Taylor plans to patent her invention. In the meantime, she’s waiting for her final college admissions results.

“To get to the Top 40, this is like post-doctoral work that these kids are doing,” says Maya Ajmera, the president and CEO of the Society for Science, which runs the Science Talent Search. This year’s top prizes went to a matching algorithm that can find pairs in an infinite pool of options, a computer model that can help identify useful compounds for pharmaceutical research and a sustainable drinking water filtration system. The finalists also voted to grant Taylor the Seaborg Award, making her a spokesperson for their cohort.

Kathryn Chu, the director of the Center for Global Surgery at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, focuses on improving equitable access to surgical care. “I think it is amazing that this young high school scientist was inspired to work on a solution to address this problem,” the surgeon writes in an email. “A product that could detect early [surgical site infections] would be extremely valuable.”

However, she adds, “how this concept could translate from the bench to the bedside needs further testing.”

Current suture threads are good at their job: they’re affordable, they’re not irritating on the skin, and they are strong enough to hold a wound together. The beet juice-dyed thread will need to be competitive on all of these attributes. Surgical site infections can also occur below the surface of a wound—a C-section involves cutting through, and then repairing, not just the skin but also the muscle underneath. As it stands, the color-changing suture thread wouldn’t help detect an infection below the skin, and “if the infection oozes through the skin, or involves the skin, the infection has already reached later stages,” writes Chu.

Lastly, the same non-absorbency that makes standard suture thread hard to dye with beet juice also keeps bacteria out, and vice versa. While cotton thread’s braided structure gives it the ability to pick up the beet dye, it also provides a hiding place for bacteria that cause infections.

Taylor has been pursuing a line of research since the beginning of her project that might counteract the risks posed by using cotton.

“I read some studies that said beet juice was antibacterial. And although I want to take their word, I wanted to try it for myself. I wanted to reproduce their results,” says Taylor.

But studying bacteria requires specific, sterile practices that neither Taylor, nor her mentors Walling and Michelle Wikner, both chemistry teachers, were initially familiar with. In the months leading up to the Science Talent Search competition, Taylor connected with microbiologist Theresa Ho at University of Iowa to create a research plan incorporating the proper techniques, and that work is ongoing.

Reflecting on the science fair experience, Taylor most wants to thank Carolyn Walling for encouraging her to participate. “We're kind of basking in all of this together,” she says, especially because it’s her first year doing independent research. She’s also thankful for the support of her community.

“I have so much school pride because when somebody in our school does something great, they're celebrated to its fullest extent,” says Taylor. “And being able to be one of those kids has been so amazing.”

After graduation, Taylor hopes to attend Howard University, study political science and eventually become a lawyer.

“I am looking forward to seeing how Dasia uses this project moving forward,” says Ajmera. “And on a long-term scale, I’m really interested in watching what problems she is going to continue to solve, to make the world a better place.”