Why Hedy Lamarr Was Hollywood’s Secret Weapon

The starlet patented an ingenious technology to help with the war effort, but it went unrecognized for decades

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/8a/358ab823-070f-4ef2-bc70-e5a3cf43eabc/nov2017_c03_prologue.jpg)

By the time American audiences were introduced to Austrian actress Hedy Lamarr in the 1938 film Algiers, she had already lived an eventful life. She got her scandalous start in film in Czechoslovakia (her first role was in the erotic Ecstasy). She was married at 19 in pre-World War II Europe to Fritz Mandl, a paranoid, overly protective arms dealer linked with fascists in Italy and Nazis in Germany. After her father’s sudden death and as the war approached, she fled Mandl’s country estate in the middle of the night and escaped to London. Unable to return home to Vienna where her mother lived, and determined to get into the movies, she booked passage to the States on the same ship as mogul Louis B. Mayer. Flaunting herself, she drew his attention and signed with his MGM Studios before they docked.

Arriving in Hollywood brought her a new name (Lamarr was originally Kiesler), fame, multiple marriages and divorces and a foray into groundbreaking work as a producer, before she eventually became a recluse. But perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Lamarr’s life isn’t as well known: during WWII, when she was 27, the movie star invented and patented an ingenious forerunner of current high-tech communications. Her life is explored in a new documentary, Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story. Director Alexandra Dean spoke with Smithsonian.com about Lamarr’s unheralded work as an inventor.

The interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Most people know Hedy Lamarr as this gorgeous, glamorous actress, not as the inventor of a communication technology. Where did Hedy Lamarr’s ingenuity come from?

Hedy's fascination with invention was very inborn; it was a natural love, a passion, and it was fostered by her father, who was a banker, but actually loved invention himself. He would point out to her how things worked, the trolley going by, where the electricity came from, and loved her tinkering, so she would do things to impress him. She would take apart a music box and put it back together again, and she just always had that kind of a mind.

What did she invent?

During World War II, she invented a secret communication system for the Allies. It was a secure radio signal that would allow Allied warships to control their torpedoes. The radio signal going from the ship to the torpedo would change frequencies according to a complicated code so the Germans couldn’t jam the signal. It inspired a secure digital communication system we use today.

How did she become interested in that problem?

As an Austrian Jew, she was very concerned about what was happening to her family left behind in Vienna. She wanted to bring her mother safely to the U.S., but Nazi submarines had blown up refugees who attempted an Atlantic crossing. As it happened, Hedy had been married to a weapons manufacturer who worked with the Nazis before she escaped Austria, so she knew the kind of torpedoes the Nazis had and wanted to design one that would give the Allies the upper hand.

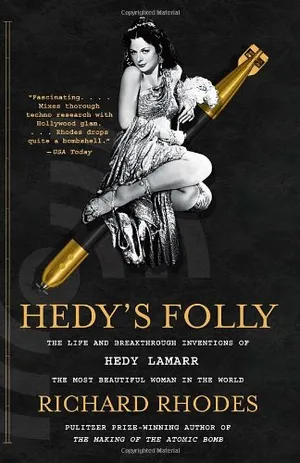

Hedy's Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Rhodes delivers a remarkable story of science history: how a ravishing film star and an avant-garde composer invented spread-spectrum radio, the technology that made wireless phones, GPS systems, and many other devices possible.

What was the role of her collaborator, the musician George Antheil?

Hedy came up with this idea [for communicating with torpedos], but she didn't know how to put it into a mechanical practice. The person who did that for her was this musician who also left school at 15 and had no science and engineering background, but he had been working with player pianos. He had tried to sync 16 player pianos for this famous ballet he did in Paris called Ballet Mecanique.

So he was the world expert in syncing these little pianos, and he was the one who said that's how we basically create this communications system in reality. We're going to put two tiny piano rolls inside the torpedo in the ship, and we'll sync that, because he knew how to do that. He was the mechanical mind. She was the concept.

And then they also brought in an engineer, right?

They got pretty far with the concept, but they took the idea to the National Inventors Council, which put them in touch with this engineer at CalTech to help them really finesse it and make it viable.

Why did the Navy turn down the frequency hopping technology?

I think the Navy was saying to themselves, look, it's a movie star and a concert pianist who left school at 15, and they don't know what they're talking about. They should go out and sell war bonds if they want to help the war effort and not do what engineers and scientists do. They didn't understand it.

But her invention was used after the war?

Her patent was handed to a contractor in the 1950s who was building a “sonobuoy” (floating submarine detection device) for the U.S. Navy. He put an updated version of her invention into his designs and from there her concept evolved into the “frequency-hopping” system we use today with Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and GPS.

What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

By far the biggest challenge in making the film was that there was no record, basically none, of Hedy talking on tape about the experience. At the time I started doing this project, a lot of people were saying to me it's a nice story, but it's not true. She didn't come up with this invention, either she stole it from her weapons manufacturer husband in Vienna, or [Anthiel] actually came up with it.

I was having scientists and engineers telling me that it was impossible that she'd done it. And I really didn't want to just say she'd done it because I wanted her to have done it.

I spent about six months reporting and just seeing if we could find some record anywhere, some hidden record that no one had ever found before of Hedy telling the story herself. We had gone through every single number and name of anybody she had ever talked to on the record, and I decided one night to try one more time and just go through the whole list. The second time around we realized for one reporter, we had the wrong e-mail for him.

And we found the right e-mail and I e-mailed him and he called me immediately, and I picked up the phone and he said, I've been waiting 25 years for you to call me, because I have the tapes.

I was in chills. I felt like I had conjured these tapes out of just pure desire and necessity, that they exist. And we were running over there, and he had five cassette tapes that had been sitting in a drawer, had gotten stuffed behind a trash can. They'd never been heard.

We started listening to them, and there she was. She was older, it was a little scrambled, but there she was. She was telling the story of what she did. So that's really astonishing. At that point I threw out the film I was making up until then, which was based on what little scraps she'd ever told, newspapers reports and some letters in German, and just started letting her tell the story in her own voice from the tapes. And that really made the film for me because it was her own story in her words.

And when it came to the invention, this question if she had copied it from her husband or George, she would just laugh and say no, I don't care what other people say. I know what I did. And she explained why she did it. So it was just wonderful to hear her say that, and then we were able to find other evidence that sort of backed her up as well.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/5f/6f5f6a10-916e-44b7-b66f-1cdcc370b4cc/nov2017_c25_prologue.jpg)

One theme that comes up in the film is her ability to cut ties. She divorced something like five or six times, and has an adopted child she distances herself from, and then she totally disassociates from being Jewish. What do you attribute this to?

Hedy was a survivor. An animal in a trap will leave the limb in the trap in order to survive, and I think she left a limb, really, in Vienna. That's why you see this longing for Vienna, but this unwillingness to go back, because she really had such a trauma in her childhood having to leave her home, her father dying, her mother being left behind. Then her husband sells out to the Nazis, and then finds out that she herself is being publicly recognized as the enemy. Hitler is saying that he won't screen Ecstasy because the lead actress is Jewish. All of this amounted to great trauma for her.

And when she escaped she really severed that limb and she never talked about her family in Vienna, and she never talked about the people she left behind or the people she lost. She couldn't even talk about her Jewish days. That's the kind of loss you're talking out in amputation. Once a person is able to do that with one aspect of their life, they retain the ability to do it with others. That is the tragedy of Hedy's life.

What discovery about Lamarr surprised you the most?

Her mother used to call her a chameleon as a child, and she was a chameleon, but not in a way that she just became other people, in a way that she was able to experience so many different sides of her own personality, from inventor to actress to movie star to producer. That was a real shock for me. She was one of the first producers in Hollywood, she and Bette Davis were the first two women to say they could produce their own movies. And Hedy more successfully than Davis. Just incredible. Somebody so willful and so powerful, and so unwilling to be boxed in by any prejudice that existed in her time was really inspiring.

How important was it to her to be recognized as an inventor?

She was far more proud of her invention than her film career. She didn’t think her films amounted to much.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.