How a $10 Billion Experimental City Nearly Got Built in Rural Minnesota

A new documentary explores the “city of the future” that was meant to provide a blueprint for urban centers across America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/21/24212515-a2c2-4e3b-b605-bcaf197c97a7/dome-headlines.jpg)

The future had arrived, and it looked nothing like what city planners expected. It was the early 1960s, and despite economic prosperity, American urban centers were plagued by pollution, poverty, the violence of segregation and crumbling infrastructure. As the federal highway system expanded, young professionals fled for the suburbs, exacerbating the decay.

“There is nothing economically or socially inevitable about either the decay of old cities or the fresh-minted decadence of the new un-urban urbanization,” wrote activist Jane Jacobs in her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. “Extraordinary governmental financial incentives have been required to achieve this degree of monotony, sterility and vulgarity.”

For Jacobs and others, federal policies only served to push cities toward greater blight rather than restoration. “There was a deep-felt concern that society was headed in the wrong direction in its ability to address the social issues of the day, e.g. segregation (of age groups as well as races), the environment, and education,” write professors of architecture Cindy Urness and Chitrarekha Kabre in a 2014 paper.

But one man had a revolutionary idea, a plan so all-encompassing it could tackle each and every one of the social issues at once: An entirely new experimental city, built from scratch with the latest technology, entirely free of pollution and waste, and home to a community of life-long learners.

The Minnesota Experimental City and its original creator, Athelstan Spilhaus, are the subjects of a new documentary directed by Chad Freidrichs of Unicorn Stencil Documentary Films. The Experimental City tells the story of the tremendous rise and abrupt fall of an urban vision that nearly came to fruition. At one point, the Minnesota Experimental City had the support of NASA engineers, Civil Rights leaders, media moguls, famed architect Buckminster Fuller and even vice president Hubert Humphrey. Many were drawn to the plan by Spilhaus’ background as well as his rhapsodic conviction for the necessity of such a city.

“The urban mess is due to unplanned growth—too many students for the schools, too much sludge for the sewers, too many cars for the highways, too many sick for the hospitals, too much crime for the police, too many commuters for the transport system, too many fumes for the atmosphere to bear, too many chemicals for the water to carry,” Spilhaus wrote in his 1967 proposal for an experimental city. “The immediate threat must be met as we would meet the threat of war—by the mobilization of people, industry, and government.”

Creator of the comic “Our New Age,” which featured new science and technology in easy-to-digest fashion (including inventions he wanted to feature in his experimental city), Spilhaus had worked in the fields of mechanical engineering, cartography, oceanography, meteorology and urban planning. He initiated the Sea Grant College Program (a network of colleges and universities that conduct research and training related to oceans and the Great Lakes), helped invent the bathythermograph (a water temperature and depth gauge used in submarine warfare), and designed the science expo for the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962. But above all, the longtime dean of the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Technology was a futurist, and the experimental city was his brainchild that combined his many passions.

Of course, Spilhaus was hardly the first person to have dreamed of an immaculate “city on a hill” that would learn from the problems of other urban areas. Industrialists like William Howland built miniature cities for their workers, city planners purposefully re-designed Chicago after much of the city burned in 1871, and Oscar Niemeyer created the planned city Brasilia in the 1950s. The difference for Spilhaus was that he didn’t want a perfect city that never changed; he wanted a science experiment that could perpetually change, and address new problems that arose.

“The idea behind a utopia was, we have the answer, we just need a place to build it,” says director Chad Freidrichs. “The experimental city was different because the idea was, we’re going to use science and technology and rationality to find the answer, as opposed to coming in and building it from the start.”

Before coming to this project, Freidrichs directed The Pruitt-Igoe Myth, a film on public housing in St. Louis. This time around, he wanted to pair his interest in urban design history with retro-futurism. He first learned of Spilhaus through the “Our New Age” comic strip, and from there became fascinated with the forgotten history of the experimental city. His new film, which premiered in October 2017 at the Chicago International Film Festival, alternates between archival audio clips and interviews with those involved in the experimental city project. The tragic story of the rise and fall of the planned city is situated in the context of national politics, as well as local opposition.

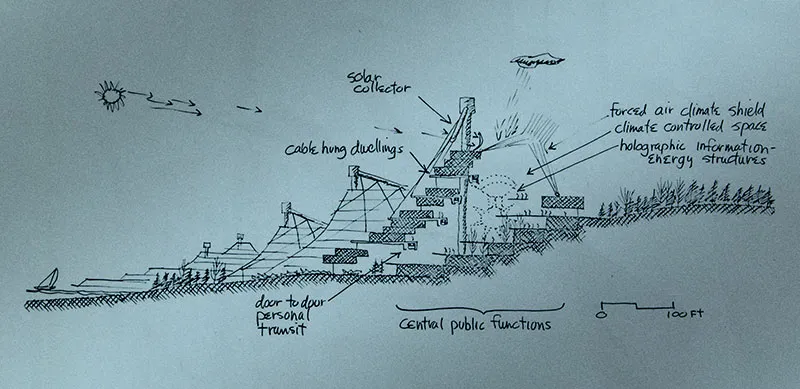

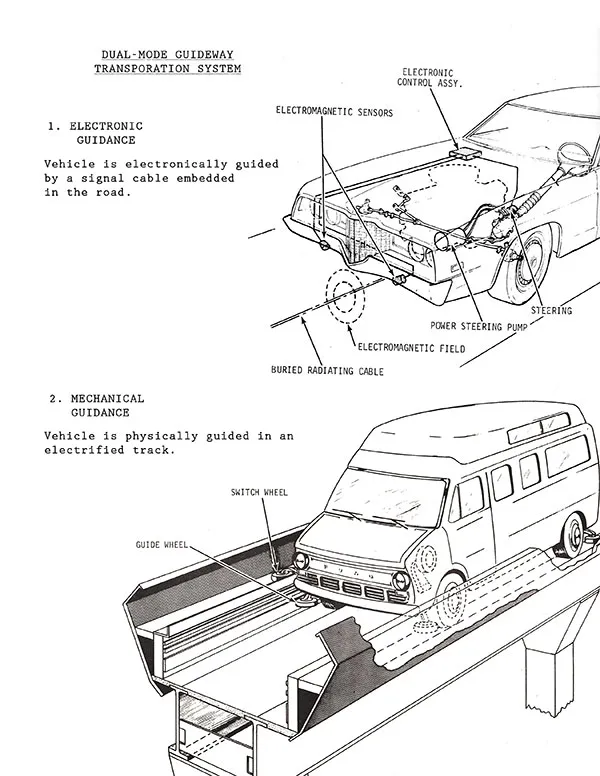

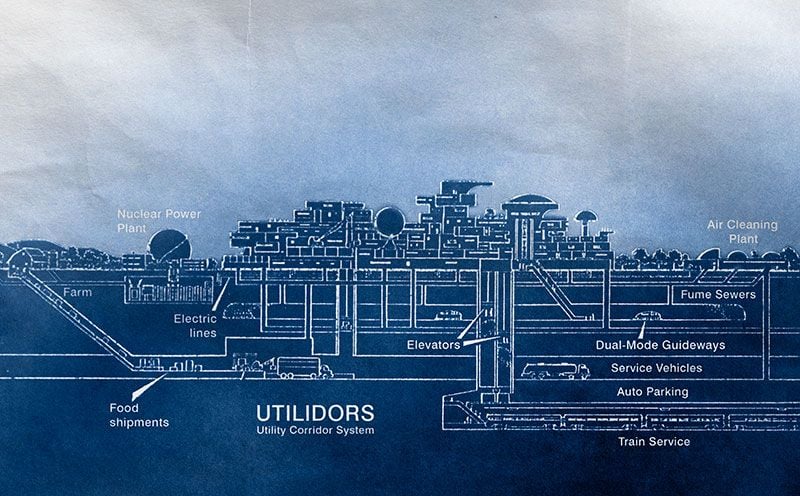

Spilhaus’ vision for this noiseless, fumeless, self-sustaining city included underground infrastructure for transporting and recycling waste; a mass transit system that would slide cars onto tracks, negating the need for a driver; and computer terminals in every home that would connect people to his vision of the Internet—a remarkable prediction, given that computers of the era occupied entire rooms and no one was sending email. Spilhaus envisioned the city holding a population of 250,000 and costing $10 billion 1967 dollars, with 80 percent private funding and 20 percent public.

For several heady years in the late 1960s and into the 1970s, the city seemed destined for success. Even after Spilhaus resigned as co-chairman of the project in 1968, it continued earning support from federal legislators. When Humphrey lost his 1968 bid for the presidency and the Minnesota Experimental City project was branded as the property of Democrats, the planning committee turned to the state. In 1971, the Minnesota legislature created the Minnesota Experimental City Authority, which was tasked with finding a site for the city by 1973.

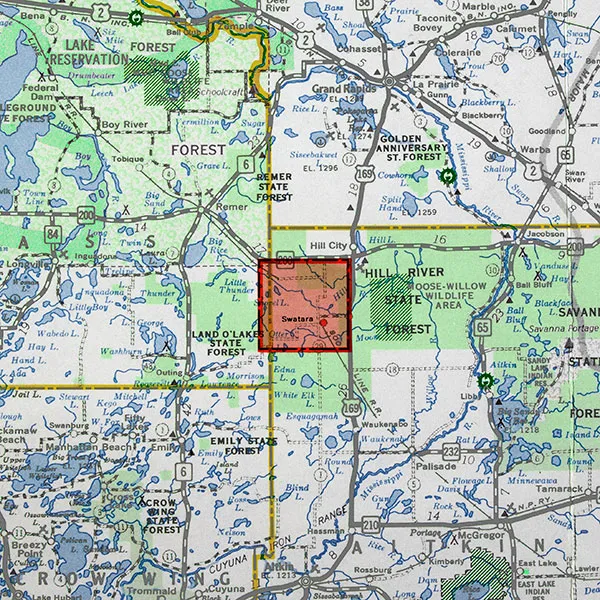

After months of searching, the committee chose Aitkin County, some 105 miles north of Minneapolis, near the village of Swatara. The land was undeveloped, far enough from any large city not to be considered a suburb and with enough room for some quarter-million residents. But no sooner had the site been chosen than citizens of the area became outspoken critics of the planned city, arguing that even an urban center with the best intentions would be unable to prevent pollution. Between the protesting residents and dwindling support in the state legislature, the Minnesota Experimental City Authority lost its funding by August 1973. In the aftermath, the project disappeared without leaving almost any trace of how close it had come to being built.

“From 1973 through 1975 the country experienced what some considered the most severe recession since WWII, with oil shortages, rising interest rates, and the reduction of real income and consumer spending. The notion that we could tackle any challenge if the ideas and effort were there seemed like an idea whose time had passed,” write Urness and Kabre.

For Freidrichs, the city was both a beneficiary and a victim of its timing. If not for the optimism of the 1960s—the Apollo era inspired all kinds of engineers to dream big—the project might never have gone as far as it did. But it also wasn’t built quickly enough to reach escape velocity; it couldn’t survive the turbulence of the 70s.

“Perhaps one of the reasons why the experimental city was forgotten was because it was a paper project and never got into building on the earth,” Freidrichs says.

But those same dreams for better cities, with more resilient infrastructure and the amenities its residents require, haven’t completely disappeared. Today, countries around the world are experimenting with how urban environments function (take Rotterdam’s floating dairy farm and experimental homes, for example). Private companies are making their own foray into urban planning as well, such as Alphabet (the parent company of Google) attempting to redevelop property in Toronto. Spilhaus may not have succeeded in his time, but others still may—and will likely discover their own set of hurdles to overcome.

“I think the desire to make the world better is crucial, especially as the population increases and the resources become fewer,” says University of Michigan English professor Eric Rabkin on the radio show Imaginary Worlds. “I like utopia because it drives us to consider how to make things happy. But that doesn’t mean I want to have it function as a blueprint.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)