How 19th-Century Activists Ditched Corsets for One-Piece Long Underwear

Before it was embraced by men, the union suit, or ‘emancipation suit,’ was worn by women pushing for dress reform

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/32/7d325dd3-9a28-4782-abde-dc3d7b7469b3/union_suit-main.jpg)

In the 1870s, many female tourists to Manhattan sought out the city's most curious boutiques—underwear stores that sold what was called “ladies' hygienic underdress.”

“Through sheer weariness they may have omitted Central Park, passed by Stewart's, and forgotten Tiffany, but the 'chemiloon' is a thing to be remembered even when the feet are blistered and the back aches with premonitory pains of malarial fever,” New York World reported in 1876. “There exists a deplorable ignorance regarding the nature and fashion of this mysterious garment, or rather combination of garments, which was introduced in whispers and is not yet discussed in ordinary tones. 'What is it?' is still the question of the masses.”

The “chemiloon,” or union suit as it was often called, was the predecessor of long johns and today's onesie—the one-piece pajamas you reach for before settling in with a cup of hot chocolate. Sure, when most people think of onesie pajamas, they probably zero in on the red flannel, full-body underwear with the bum flap—worn by the likes of Paul Bunyan, or by men with a predisposition for thick mustaches—not 19th-century women’s intimate drawers. But the now “male coded” union suit was actually a game changer in the women’s rights and dress reform movements.

Dress reform movements freed women from painful corsets, heavy bustles and disease-sweeping long skirts. “The great weight of their cloth dresses and huge cushioned bustles is something terrible to think of,” The Daily Republican wrote in 1886. “Steels were put into their dress skirts to make them stand out. The weight of the goods crushed the corners of these steels and drove them into the flesh of women's backs, till in some cases the skin was actually scraped off their bodies as they walked.” The union suit undergarment was touted as a healthier alternative to corsets, first during the more radical women’s rights movement that fought for equality from 1850 to 1870, and then during the post-1870 movement that was run by upper-class clubwomen in social organizations who finagled reform by working within the confines of their gender norms.

According to Patricia Cunningham, author of Reforming Women's Fashion, 1850-1920: Politics, Health, and Art, one of the first union suits was patented in 1868, and called the “emancipation union under flannel.” The garment combined a knit flannel shirt and pants into one piece. The long pants extended to the ankle, nixing the need for long stockings and garters, and later versions would have rows of buttons at the waist to help suspend several layers of skirts, discouraging the use of heavy petticoats that often weighed upwards of 15 pounds. Most importantly, it “emancipated” women from the pinching confines of the corset.

While it sounded like a much more comfortable option than metal crinolines and tight corsets, not many “ordinary” women rushed to buy the undergarment. Instead, it was mostly found in feminists’ wardrobes. During the first wave of the dress reform movement, which was led by prominent suffragists and women’s rights leaders like Amelia Bloomer, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck in the northeast, the union suit was part of a packaged deal that would free women from frivolous fashions and make them more equal to men. Some of these activists not only championed comfortable underwear, but they also wanted to change clothing norms as a whole, which included removing bulky bustles, shortening skirts to the ankles and wearing them over pantaloons, often referred to as “bloomers.”

“Woman's dress...how perfectly it describes her condition!” Elizabeth Cady Stanton said in 1857. “Her tight waist and long, trailing skirts deprive her of all freedom of breath and motion. No wonder man prescribes her sphere. She needs his aid at every turn. He must help her up stairs and down, in the carriage and out, on the horse, up the hill, over the ditch and fence, and thus teach her the poetry of dependence.”

An early version of the union suit was worn by reformer Mary Walker, one of the more radical activists in the women’s movement. The Oswego, New York native was the only female surgeon during the Civil War, the first and only woman to ever receive the Medal of Honor, and was known for her penchant for wearing trousers and suspenders—an affinity that got her arrested on more than one occasion. She believed tight garters and corsets “shackled and enfeebled” women, and designed what she called a “Dress Reform Undersuit” in 1871 as an alternative.

“It’s important to remember that this was a garment that was worn by dress reformers, rather than the wider population. It was part of a type of anti-fashion clothing that aimed to be healthy, hygienic and outside contemporary trends,” says Rebecca Arnold, senior lecturer in the history of dress at The Courtauld Institute of Art in London. “Dress reformers argued that women’s fashions rendered them incapable of much movement. Corsets could squeeze the chest and make breathing shallow, and the sheer bulk of skirts made it difficult to walk fast or navigate spaces with ease. To dress reformers, the layers of garments and additional trimmings also had a visual impact—making women look as though their role in life was to be decorative.”

The union suit was initially embraced by some of the press, with reporters applauding the garment’s convenience and thriftiness. In 1873, The Vermont Gazette reported that union suits were in such high demand that the local knitting mill had to employ night shift workers in order to catch up with orders. “They are at present about two months behind on their orders,” the paper reported. In 1876, The True Northerner called the undergarment “a useful adaptation of a novel idea for ladies' underwear” that “ought to become very popular.” The Michigan paper observed that not only did the union suit protect the entire person, but it also had the added perk of doing away “with the double thickness caused by the overlapping of the vest.” In 1878, The Evening Star thought the union suit was brilliant for travel, and wrote about it with the same kind of fanfare travel bloggers write about non-bunching, space-saving hipster briefs today. “The underwear is also a matter of importance in taking a long journey, as the less trouble, the more satisfaction, and least time wasted. As a matter of economy, the fewer pieces, the better; and therefore the Union suit, which is simply drawers, chemise and corset cover, is by all odds the most desirable garment.”

At the same time, dress reform in general attracted negative attention from the 1850s through the 1900s, especially when Walker and other activists began to dress in bloomers and other traditionally male clothing. This terrified both men and women alike, but men in the mainstream press and men who had control over the media were the most vocal critics. Slipping on men’s clothing signaled an expectancy to slip into their access to power, and because of this power grab, dress reformers were accused by male journalists and editors of ugliness, cross-dressing, even insanity, as a way to dissuade other women from participating. Women who persisted in wearing bloomers and other reformed clothing endured what suffragist Mary Livermore called “daily crucifixion,” and the term “bloomerism” became synonymous with feminists who drank, abandoned husbands, cross-dressed and partook in general debauchery.

That’s why the second wave of activists, who were mainly northeastern and midwestern clubwomen, decided to take a softer approach to dress reform. Rather than altering a woman’s outward appearance, activists from 1870 to 1900 instead focused on changing her undergarments, pushing to loosen the corset and remove weighty petticoats. Reformers like Frances Russell, Olivia P. Flynt and Abba Goold Woolson cloaked these changes in an argument for healthier living, and joined the health reform movement.

“As cities got bigger, more populated, and dirtier, and as medicine and the study of medicine increased, there was an increasing call to address women's clothing,” says Andrea J. Severson, a scholar of fashion and rhetoric in Arizona State University’s Department of English who studied the language of the press in the early 1850s in response to the dress reform movement. “Disfigurement from corsets—though this was more rare, but made for good headlines—and long trains that swept up all kinds of dirt and trash outside and brought it into the home, both factored into this call to modify women's dress.”

The respected, upper-class clubwomen promoted the idea that women could achieve beauty through healthy dressing. Abba Goold Woolson set up lectures in New England with prominent female doctors to discuss the health advantages of dress reform, for example, and Frances Russell, the chairman of the Dress Committee of the National Council of Women, lectured how healthy dress could aid women in being better mothers.

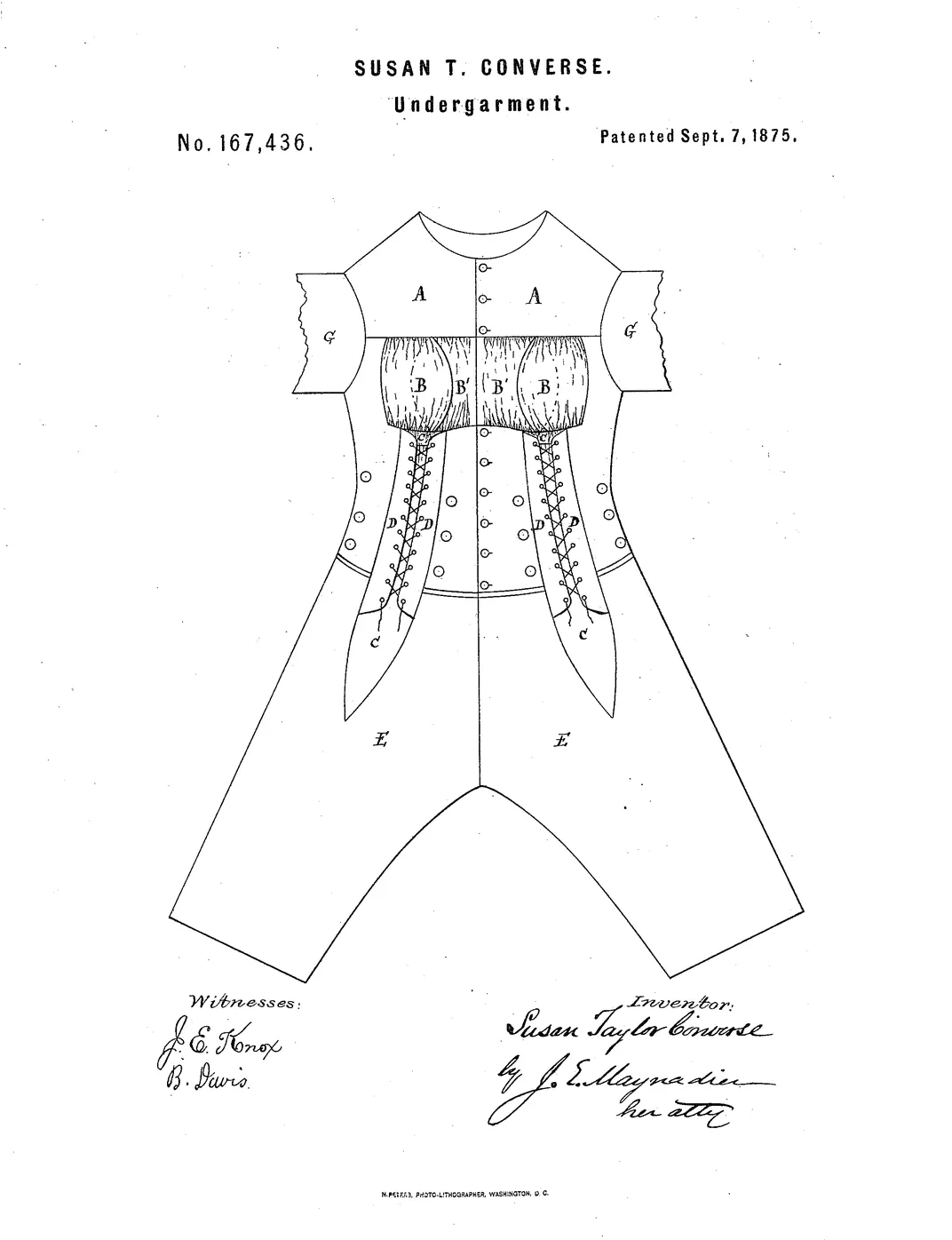

In 1875, Susan Taylor Converse from Massachusetts patented an upgraded version of the union suit, and dubbed it the “emancipation suit.” The year prior, Converse displayed her emancipation suit at an exhibition of reform garments held by the New England Women's Club, which was one of the earliest organizations to advocate undergarment reform. The club gave Converse’s onesie its stamp of approval, and her suit became the first to attract widespread public attention.

The undergarments were mainly sold by the New England Women's Club or lecture-touring reformers, but with varied success. In 1874, the Club opened a dress reform shop in Boston on 25 Winter Street, a popular shopping area in the city. While orders began to come in from across the country, mismanagement caused the garments to be poorly made, which turned off shoppers. Around that same time, journalist and dress reformer Kate Field started a women's dress reform store in New York City, and created a window display with her sensible intimates to attract customers. But as The Kansas City Star gleefully explained, not many passersby were fans of the underpinnings. “The styles were so hideous that men, and women too, would cross over on the other side of the street to keep from looking at the frightful garments,” the paper wrote. On the other hand, dress reformer and designer Annie Jenness-Miller sold her patterns through the mail, allowing women to make the undies themselves or go through seamstresses—a successful effort thanks to Miller’s glamorous and traditionally feminine reputation.

When the suits were advertised in newspapers, the copy made an appeal to husbands’ wallets. “The cry of 'hard times!' is still heard on every hand, but is it not true that in our history as a nation it never required so many yards of costly material for a woman's dress?” asked an 1875 ad for the emancipation suit in The Boston Globe. If the suit was adopted, the ad promised, it will “give to fathers' and husbands' heads and purses a respite from care and expense.”

Men also adopted the union suit because of its comfort. “For men, the union suit was warm and practical, its use extended far beyond dress reformers to become a staple for many men in the late 19th and early 20th century.” Arnold says. “It is not exactly the same as the women’s version. But an aspect of dress reform was a utopian belief in blurring gender in dress to make it more practical for both sexes.” There were some key differences between the gendered union suits—men’s suits lacked buttons to hold skirts and didn’t have a ruched bust for support, as some of the women’s suits provided.

Criticism of men wearing “women’s undergarments” was kept at bay because the union suit already mimicked something in men’s wardrobes: bathing suits. According to Daniel Delis Hill, fashion historian and author of History of World Costume and Fashion, men’s union suits were a natural extension of earlier versions of men’s one-piece knit swimsuits developed in the 1850s by knitting mills.

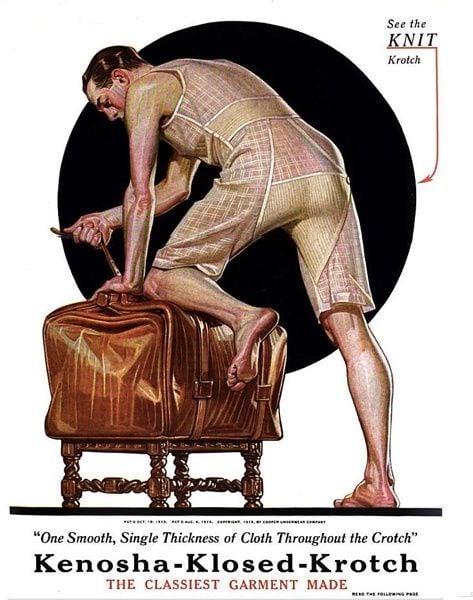

“Combinations, or union suits, are growing in favour for gentlemen's wear, as they allow a fine feeling or ease in movement,” a 1910 ad for Atheenic Mills Company explained. “There is no rucking up as with an undershirt, and the tightness of pant bands round the waist is avoided.” As interest in the underpinning waned for women in the turn of the 20th century, the onesie stayed popular for men, and in 1911, S. T. Coopers and Sons’ Kenosha Klosed Krotch union suit became the first national print advertisement for men's underwear. Oil paintings of men bending over suggestively in their onesies ran in the Saturday Evening Post, bringing an unexpected punch of sex appeal to the previously homely piece.

Women moved on from the suit not because it was a flash-in-the-pan fad, but because social conventions were too hard to defy. “For women, the pressure to conform to body ideals means it can be difficult to reject more restrictive underwear completely, except for women in rural and working class communities for whom practicality was often a more important concern,” Arnold says.

After the 1910s, the suit became a male-gendered staple, and its ties to the emancipation suit and the women’s rights movement began to fade from public memory. Men more widely adopted the suit because it wasn’t a political garment for them, allowing them to buy it without backlash. But while men buttoned farm clothes and business suits over their onesies, dress reformers continued to fight to loosen the ties of their corsets, even as society kept trying to lace them back in.