How the 2020 Presidential Race Became the ‘Texting Election’

Campaigns took full advantage of text-to-donate technology and peer-to-peer texting to engage voters this election cycle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/f6/84f6c1ec-44c0-4616-911d-5dd47a2a0969/vote_2020-main.jpg)

In the summer of 2002, Marian Croak tuned in to “American Idol” every Tuesday and Wednesday night. The inaugural season captivated millions of viewers, and after each episode, fans could vote for their favorite performer by calling a 1-800 number.

As callers excitedly dialed in their votes, Croak, an engineer with AT&T at the time, worked behind the scenes to make sure the system hosting the voting didn't collapse. The carrier was responsible for hosting the call-to-vote network, and Croak was responsible for ensuring that the system could handle the millions of calls that came flooding in after each live show.

Towards the end of the “American Idol” season, when the stakes were high, the viewers frantic, and Kelly Clarkson closed in on her win, the network was overwhelmed by calls and started failing, leaving Croak and her team to quickly reroute the traffic and save the voting process.

“There was such a surge of traffic, with people being so excited to get in as many votes as they possibly could for their favorite star, that the networks would go down,” said Croak, in an interview with the United States Patent and Trademark Office last week. “It was a nightmare. A nightmare.”

To circumvent the problem, Croak and her team came up with a new idea to offload the traffic from the network. “We thought, 'Well, why don't we just allow people to use what was called SMS and let them text their votes into the network?'” she says. “That would offload a lot of calls.”

AT&T patented the invention, and for the show’s second season, “American Idol” switched to a text-to-vote system, making the voting process more effective and secure.

A few years later, in 2005, Croak was watching news coverage of Hurricane Katrina, which would turn out to be one of the most destructive on record. As the storm made its way inland, the levees protecting the city failed, the dams broke and New Orleans drowned. People across the world watched the tragedy unfold, and Croak was no different.

“It was horrific to watch what was happening. Many people felt helpless, and they wanted to help," she said in the USPTO interview. “Sitting there watching that, I thought: 'How can we get help to them quickly?' And that's when I thought about the concept of using text-to-donate.”

To do so, Croak and her co-inventor, Hossein Eslambolchi, an engineer and then an executive at AT&T, configured a new interface that allowed people to pick up their phones, text a keyword to a five-digit number and immediately donate a set amount—usually $10—to the cause. Then the phone provider would take care of the logistics, add the donation to the phone bill and transfer the funds to the charity or nonprofit.

AT&T also applied for a patent for the text-to-donate technology, on behalf of Croak and Eslambolchi, a couple of months after Hurricane Katrina, but it would take five more years before the patent was granted and the world saw the invention in action. In 2010, Haiti experienced a catastrophic earthquake that killed more than 220,000 people and injured 300,000 more. Across the world, television viewers watched the aftermath of the earthquake unfold on the news. Thanks to a Red Cross program that used Croak’s technology, those heartbroken and aching to help could text “HAITI” to 90999 to quickly donate $10 to relief agencies. In total, Croak's innovation helped raise $43 million in donations.

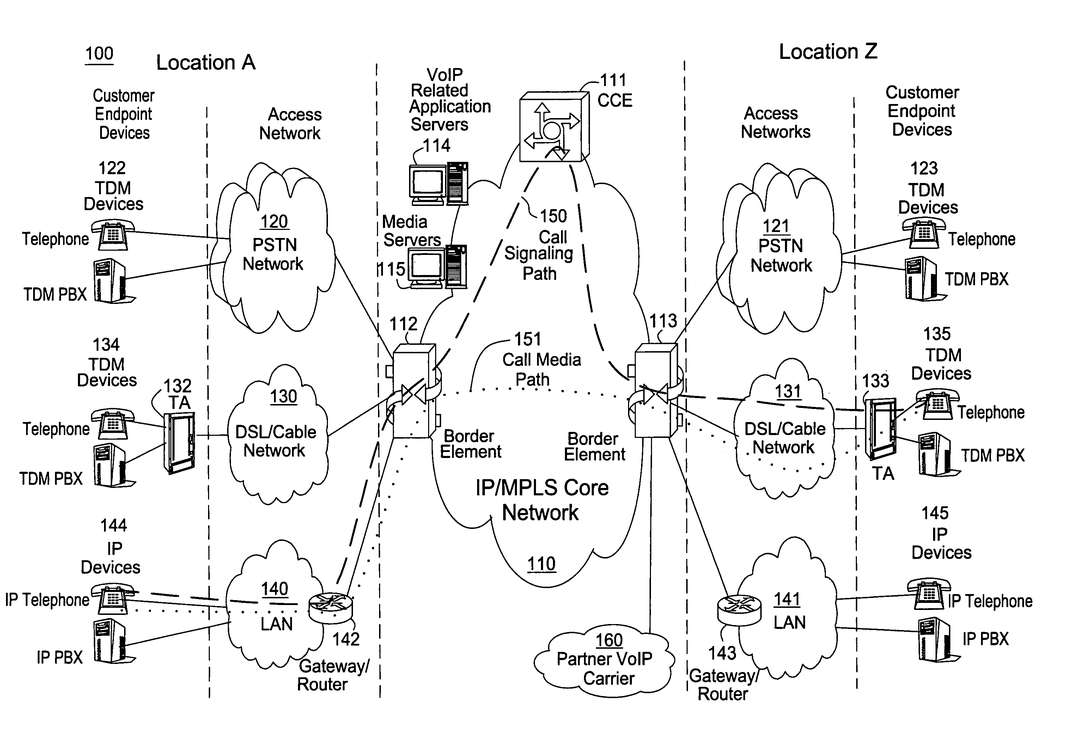

Finding innovative solutions to pressing problems is Croak’s modus operandi. She's a life-long inventor and holds more than 200 patents—around half relate to Voice over Internet Protocol (VOIP), the technology that converts sound into digital signals to transmit over the internet. Now, she serves as the vice president of engineering at Google, where she spearheads Google's initiative to extend internet access to communities across the globe, especially in emerging markets.

The massive success of the fundraisers for Haiti proved three things to be true: the technology was available and ready to use; people knew how to use it; and text-to-donate was clearly an effective fundraising mechanism. Politicians took note.

Nearly a decade ago, Melissa Michelson, a political scientist at Menlo College in Silicon Valley, conducted a study in cooperation with local election officials to see if sending unsolicited text messages to registered voters of San Mateo County could increase voter turnout—and they did. After publishing her findings in the journal American Politics Research, other scholars inquired about replicating the experiment in other counties or adapting the technology.

Although charities and non-profit organizations could use the text-to-donate technology to solicit funds, it wasn't allowed to be used for political campaigns until the Federal Election Commission (FEC) gave the green light; political fundraising via text had never been done before. In 2012, the FEC opened the floodgates with less than six months left in the presidential race between incumbent President Barack Obama and former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney. In a swift turnaround, the two campaigns rapidly assembled their text-to-donate fundraisers, but it was so novel that state and local elections didn't have the funds or expertise to adopt the fundraising tactic so quickly.

The texts sent in 2012 barely resemble those sent during the 2016 election—much less this year's races. With more campaigners well versed on text-to-donate technology and the FEC's rules set in stone, politicians in the 2016 presidential primary mobilized their texting strategies to fundraise right out of the gate, and leading the texting race was Senator Bernie Sanders. His grassroots campaign relied on small donors, and by texting “GIVE” to a short code, supporters could automatically donate $10 to his campaign.

Sanders “was really on the cutting edge” of fundraising via text, says Simon Vodrey, a political marketing expert at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. It was especially important for the Sanders campaign because it ran on small dollar donations, Vodrey says, and for politicians trying to maximize small donations, texting is the avenue to do so.

“[Donating via text] is easier and more impulsive,” Vodrey says. “It's the same thing [politicians] noticed when it was in the philanthropic application with the Red Cross—people are more willing to chip in 10 or 15 bucks if they can attach it to their cell phone bill and make that donation just through text [rather than] giving out their credit card information on a website. It feels more natural, more effortless, more frictionless.”

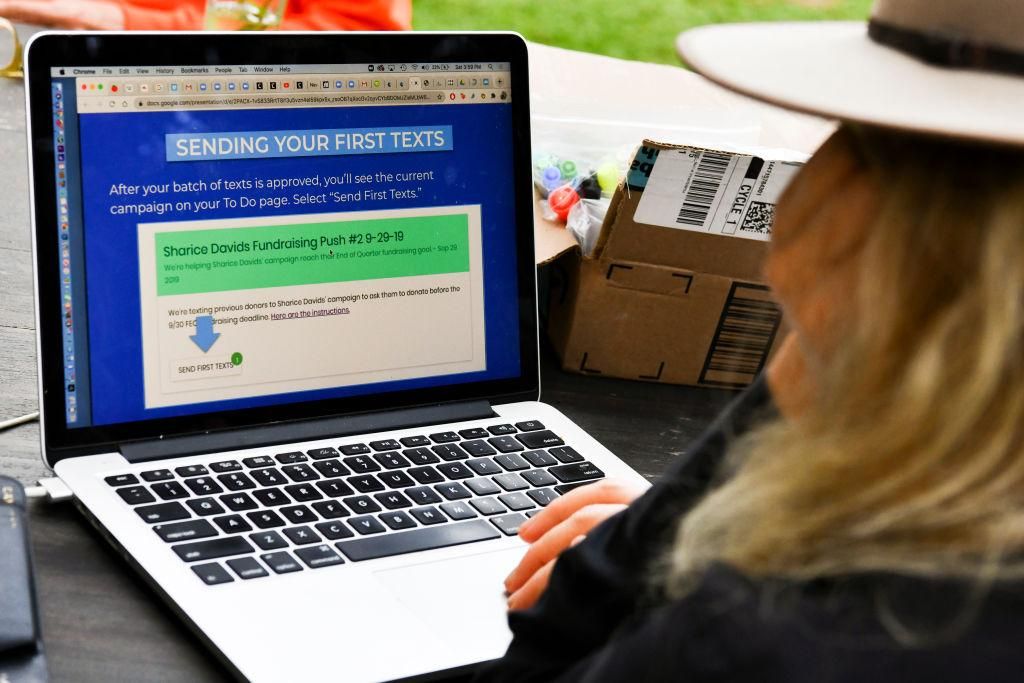

But the Sanders campaign took texting a step further: It launched a peer-to-peer texting initiative, the first of its kind to be used in American politics. The FEC deems it illegal to mass text a group of people who haven't consented, but peer-to-peer technology allows people to individually text others. As a result, texting evolved from mostly soliciting donations in the 2016 election to mobilizing and informing voters in this year's race.

Volunteers are usually the ones sending the texts, and the software allows them to do so remotely. They log onto a platform—hosted by companies like GetThru and Hustle for Democrats and RumbleUp and Opn Sesame for Republicans. The software pulls the names, phone numbers and locations of voters in an area from both public and private databases and plugs the information into a text: “Hi! It's (volunteer's name) with (campaign name). You can find your polling place at www.vote.org/polling-place-locator. Do you have any questions I can help answer?” Then, the text is sent from a real phone number, opening the door for a two-way conversation, which mass texting doesn't allow for.

“The technology was meaningfully different [from mass texts],” says Daniel Souweine, the CEO and founder of GetThru, a peer-to-peer texting platform for Democratic candidates that is currently partnering with the Joe Biden for President campaign. “When you get a message from another person, you get the feeling like someone just texted you. You don't necessarily know the person, but you're immediately in a potential conversation.”

Souweine joined Sanders' campaign in early 2016 and ran the peer-to-peer texting program, which aimed to mobilize voters and recruit volunteers. The technology could facilitate a dialogue, so recipients could ask senders questions like: How can I volunteer? How do I vote? Where do I submit my ballot early?

It quickly became clear that peer-to-peer texting was “an unbelievably powerful organizing tool,” Souweine says. His “eureka moment" came early on in the campaign when he was tasked with texting 100,000 people in seven different states, asking them to come knock on doors in the swing state of Iowa. Five percent of recipients replied yes. “The response was just unbelievable,” he says.

Five to ten percent of people will read an email, Souweine says, but 80 to 90 percent of people will read a text. “Right then and there we just saw quickly that if you wanted to reach out to people, especially your known supporters, and get them to step up and do more, texting was very quickly going to be one of our most powerful, if not our most powerful, tools,” he says.

On the political playing field, new, effective technologies are immediately snatched up, and the Sanders campaign proved just how powerful peer-to-peer texting could be. It wasn't long before campaigns at all levels of government adopted the technology, which leads us to where Americans are right now. The 2020 presidential election has been dubbed the “texting election.”

“It’s safe to say that easily a billion text messages will be sent this election,” Souweine says. Michelson says she feels like she “created a monster.” Now, that monster has revolutionized how campaigns engage voters. Most of the texts are geared towards voter mobilization, to encourage Americans to register to vote and to do so on time.

“I definitely would say I'm surprised [by this], partly because when we did [the study], we didn't really think campaign candidates could use [text] because of the law,” Michelson says. “It seemed like something only election administrators could do to help get out the vote. I really didn't anticipate that [so many groups would use it.] That's why I do sometimes feel like I created a monster because now everyone's using it, and I'm getting tons of texts.”

But Michelson says she can't blame campaign managers for the onslaught of text messages she receives—sometimes 10 in a day—because the technology has proven to be so effective. The bottom-line of the texts is to mobilize citizens to vote, and “if what it takes is people getting multiple text messages reminding them about the election and urging them to make their plan, I'm all for it.”

The need to reach out to voters is even greater now because of the Covid-19 pandemic, says Souweine. This year, door-to-door canvassing and street-side voter registration feel like relics of the past, so texts are a feasible, remote way to fill in that gap.

Michelson and Souweine agree that the texts from this year’s election won’t be the last you receive from campaigns. In fact, they predict that the technology will continue to become more powerful and influential as political campaigns learn how to fine-tune their strategies.

“I don't think it's going away at all,” says Vodrey. “There's no question [that texting] will be further refined, but I just don't know how far they can push it. I think the big danger would be for campaigns to overplay their hand with that information, to over-spam or over-solicit people. It will probably continue to be used widely, but I do think there's a limit to what you can do with it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rasha.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rasha.png)