Few things feel better than whiling away the day on a shady porch, nestled in the deep recline of an Adirondack chair. Its hallmark sloped backrest, canted seat and paddle-like armrests make it easily recognizable far outside its namesake region. Occasionally retitled and regularly reinvented in polyethylene and plastic, the chair has become a fixture on lakeshores in Michigan, beach cottages on Cape Cod and grassy front lawns across the nation.

What’s less recognized is that the chair that invites us to lounge lazily for hours originated amid a turn-of-the century health crisis, during which reclining in the fresh outdoor air seemed the only available cure.

“It is a chair rooted in the history of disease,” is how artist and furniture maker Daniel Mack put it in The Adirondack Chair: A Celebration of a Summer Classic, a 2008 tribute to the quintessential piece of porch furniture.

Throughout the 19th century, the bacterial lung disease tuberculosis—known as “consumption” for the way it wasted, or consumed, its victims—had plagued America’s expanding cities. By the time the bacterium causing it was identified in 1882, it was responsible for 1 in 7 deaths worldwide. It was the leading killer in turn-of-the-century New York, where it claimed 9,630 lives in 1900, a rate of 280 per 100,000.

It had already become fashionable for people of means to escape the stifling urbanization by fleeing northward to the mountains, where they could reconnect with nature through hunting, fishing and hiking. This led Marc Cook, a New York City office worker stricken with tuberculosis, to take to the mountains in a last-ditch effort to restore his health. He recovered, and shared his experience in an 1881 book titled The Wilderness Cure.

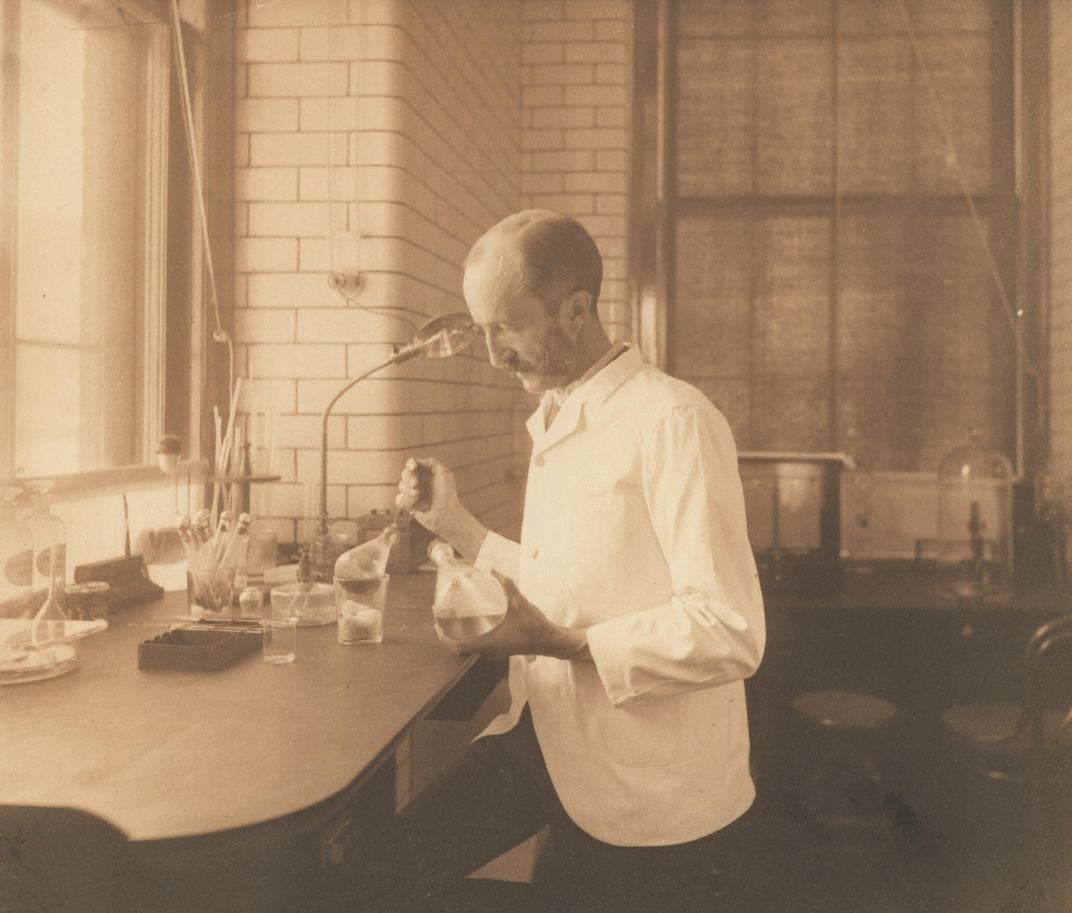

The phrase “wilderness cure”—and the reputation of the mountain region as a healing environment—led to the establishment throughout the Adirondacks of sanatoriums to treat growing numbers of TB sufferers seeking to regain their health. Three years after Cook published his account, New York physician Edward Livingston Trudeau likewise turned to the mountains to save his own life. “He basically came up here expecting to die,” says Amy Catania, executive director of Historic Saranac Lake. Trudeau not only survived his tuberculosis but remained to establish a sanatorium and laboratory dedicated to TB research and treatment.

A key part of that treatment involved prolonged exposure to the region’s cold, dry mountain air. “It’s one of the things you notice when you come to the Adirondacks,” notes Catania. “The air smells better, feels better.”

Though a purveyor of the “wilderness cure,” Trudeau himself rarely used the term. “He believed in science,” Catania says, noting that most patients who recovered from TB did so as the result of good nursing. “Being in the fresh air was part of it, but he didn’t claim any magical restorative power in the air.”

Still, the mystique surrounding the curative powers of resting outdoors took hold—even as coffins of those who succumbed while “taking the cure” were shipped out under cover of darkness. “Plenty of people died, but enough were able to recover and find their health here, so there were people who came here with a lot of hope,” Catania says.

Throughout Saranac Lake, enterprising residents rented homes out as “cure cottages” where tubercular city dwellers could take a chance on the cure. Boarding houses added “cure porches”—spacious, open-air balconies where patients could spend hours outdoors.

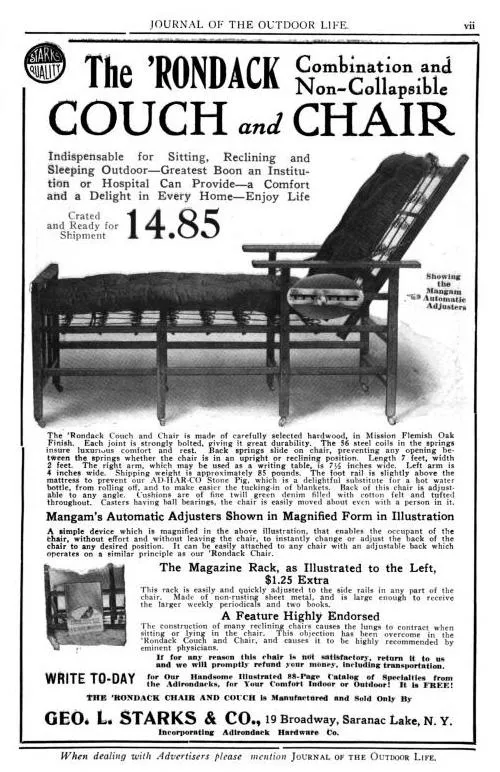

At first, patients sat outside on collapsible steamer chairs or rockers or pulled two stationary chairs together to get comfortable. “They look kind of cold and miserable,” Catania says, referencing photographs of patients bundled in blankets, their feet resting on wooden armchairs. Around the turn of the century came an improvement: The “cure chair,” a chaise lounge-like recliner modeled on those used in European sanatoriums. With wide armrests, an adjustable back and springs that supported a tufted cushion, “It really gave people a much more comfortable way to lie outside,” Catania says. Production of the chairs ensued, with several area residents receiving patents on their designs. Most adopted the lounger profile, but at least one was designed as a reclining chair.

Meanwhile, about 40 miles west of Saranac Lake, Boston native Thomas Lee set about making a simple but comfortable chair from which family members could enjoy the view of Lake Champlain from behind the Lee’s summer home in Westport, New York.

According to Elizabeth Lee, Thomas’s great- great-grandniece, “Uncle Tom” spent the years between 1900 and 1903 experimenting with different types of wood and various shapes, sizes and positioning before arriving at an angled chair with a comfort level unmatched by any other.

“There’s no comparison, if they don’t have the right dimensions,” she says, reclining in a replica chair outside Heritage House, a visitor and community center in Westport. “I can sit in one of these chairs for hours. I can sleep in these chairs. All of us want one to have because they’re so comfortable.”

Lee used 11 boards to make a wide chair with a solid-plank back set at a roughly 90-degree angle to its sloping seat. Its 9 ½-inch wide armrests were set high enough to lift the chest when elbows are rested upon them. Whether or not Lee was aware of it, his chair’s board construction reflected the region’s long tradition of simple, practical furniture made by homesteaders and local carpenters.

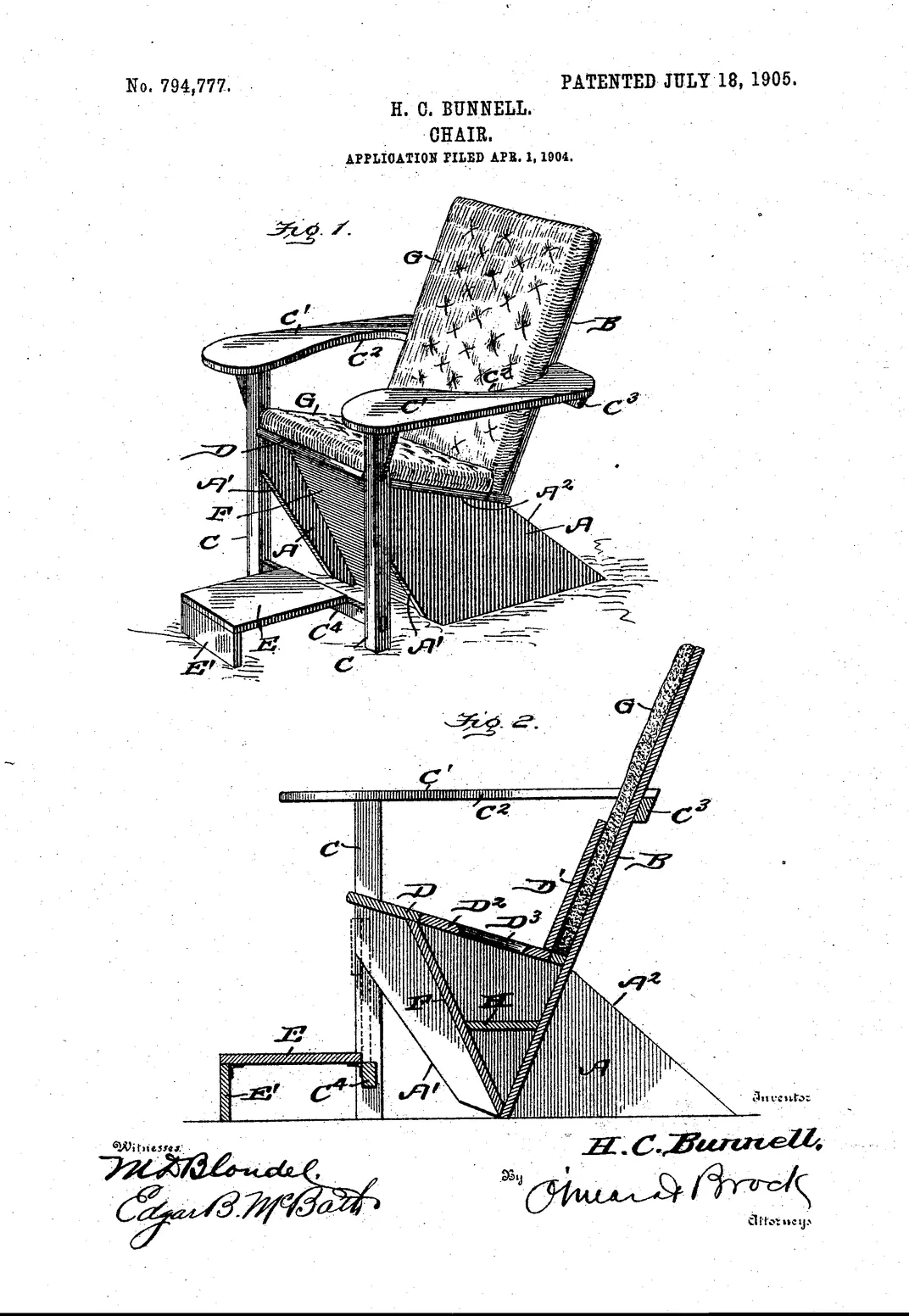

The design proved popular, and Lee made a number of chairs for family and friends. Then, in 1904, when his hunting pal, Harry C. Bunnell, found himself without a source of winter income, Lee handed over the plans to his chair. And Bunnell, without Lee’s knowledge, received a patent for the design—with a few added features.

The chair Bunnell patented had the same wide armrests, plank back and angled seat as Lee’s invention. But it also included a tufted cushion, a drop-down footrest and what appears to be accommodations for a bedpan. He described it as “a chair of the bungalow type adapted for use on porches, lawns, and at camps, and also adapted to be converted into an invalid’s chair.”

“If I were a geneticist, I would say they would be different species of the same family,” says Craig Gilborn, former director at the Adirondack Museum, now known as the Adirondack Experience, in Blue Mountain Lake. Gilborn pointed out the similarity between the cure chair and the Lee-Bunnell “Westport chair” in his book, Adirondack Furniture and the Rustic Tradition.

“Here’s this guy, he’s selling chairs to these city people coming up in Westport at the very same time that there is this large movement of hundreds of people going to the Adirondacks for their health,” Gilborn says. This, he says, “opened up a whole market for convalescent furniture” that Bunnell was eager to exploit.

In his own book, Daniel Mack, the chairmaker, suggests a kinship between the Westport chair and forerunners that include reclining patient chairs of the early 19th century as well as the slant-backed Morris chair that inspired Craftsman furniture maker Gustav Stickley. But he singles out the cure chair as a pivotal development. Were it not for tuberculosis, he writes, “It’s unlikely that there would have been an Adirondack chair.”

At the time, makers of cure chairs were likewise hoping to broaden their appeal. With names like “The Adirondack Recliner” and “The ’Rondack Combination Couch and Chair,” convalescent chairs were marketed to healthy individuals as well as the infirm.

“Our great specialty is to supply everything that an Invalid needs; but a stock so large and varied as ours necessarily runs into comforts and luxuries that well folks want,” reads an advertisement of the Sargent Manufacturing Company of New York, maker of a variety of invalid chairs.

“I really think it was a marketing thing,” says Laura Rice, currently chief curator of the Adirondack Experience museum, which has both cure chairs and Westport chairs in its collection. “There were a lot of stores selling (cure furniture); that may have been his [Bunnell’s] intent.” She adds, however, that she’s never seen a chair with Bunnell’s modifications, and noted that the low profile of the Westport chair itself is not particularly suitable for someone in a weakened condition.

While cure chairs were specifically designed for TB sufferers, Catania notes that the frequency with which tuberculosis patients come in and out of remission blurred the line between who was ill and who was not. “There was this idea you had to take care of your health,” she says. “People slept out on their cure porches even if they weren’t sick with TB.”

It wouldn’t be the first time that furniture designed for the sick or infirm crossed into the mainstream, says Patricia Kane, a curator of American Decorative Arts at Yale University Art Gallery, who obtained a Westport chair for the collection in 2002. A classic example is the wing chair, whose dual protuberances were likely designed to support the head of elderly or infirm occupants and which—like Bunnell’s patented chair—were sometimes fitted with commodes. “Nowadays they’ve migrated into our living rooms, and we think of them as living room furniture,” Kane says.

Regardless of intent, the Westport chair’s combination of a slanted back and high, supportive armrests makes it a particularly good seat from which to take a breath, notes Mack. “The chair opens your chest up when you sit in it,” says the author. “It might have been the poor man’s cure chair.”

According to Mack’s book, Bunnell produced his “Westport Plank Chair” in a basement workshop and sold them for $4 out of a retail store on the town’s main street. By 1912, a version called the “Adirondack Bungalow Chair” was being sold through W.C. Leonard’s department store in Saranac Lake, and copycats soon followed. Bunnell continued to manufacture the chair himself until about 1930, producing variations that included an alternate-facing tête-à-tête version and another that converted to a rocking chair. By the time Bunnell died of pneumonia in March 1933, his chair design had found its way beyond northern New York. The newspaper notice announcing his death hailed him as the “manufacturer of the world-wide known Adirondack camp chair.”

By the 1950s, the introduction of antibiotics and other treatments for tuberculosis made the sanatoriums obsolete and cure chairs unnecessary. “When the TB years ended, a lot of them were sent straight to the dump,” says Catania, who still owns one and uses it for reading—until it lulls her into a doze. “They’re really good napping chairs.”

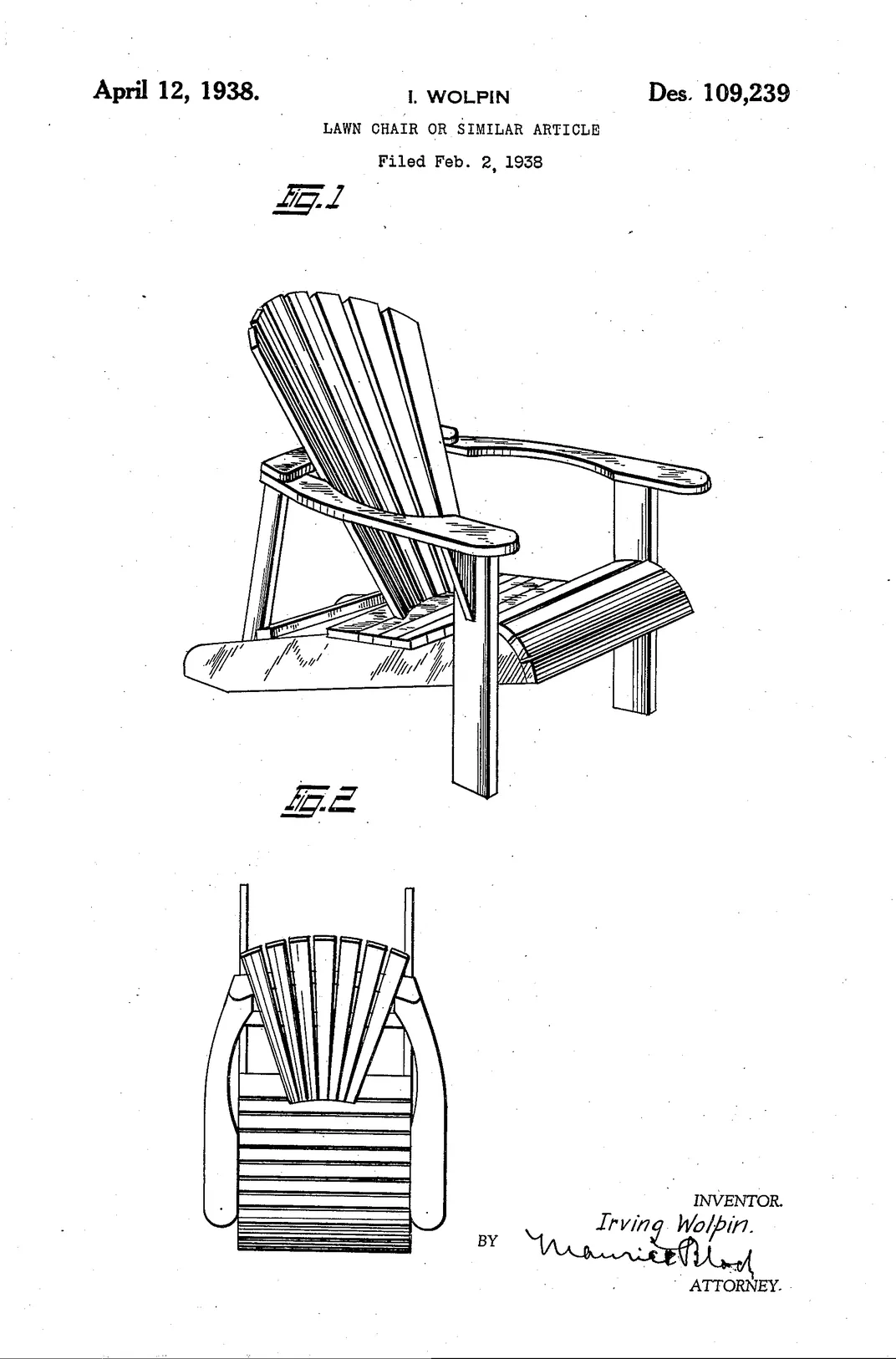

But Lee and Bunnell’s slant-back chair endured. Permutations of the original design continued to appear, some from the workshops of weekend hobbyists, and others from the loftier circles of furniture designers like Gerrit Rietveld, whose 1918 “Red and Blue Chair” and boxy 1934 “Crate Chair” exhibit similar DNA. In 1938, Irving Wolpin of New Jersey patented a chair in the Westport form with a fan-shaped back and slats where Lee and Bunnell had used planks. It’s essentially the version we recognize today, and it appears throughout the Adirondacks, and even in Westport, where Lee’s design still holds court on some porches.

Gilborn acknowledges that the multiplicity of designs and dearth of documentation make it difficult to be definitive about the chair’s heritage. But that, he says, exemplifies the wilderness spirit from which it was born. “Going to the Adirondacks you leave everything behind, including the rules of behavior and documentation,” he says. “It’s part fun and part irresponsibility.”

Bunnell never secured Lee’s permission to alter his invention, or to market it. But by all accounts, Lee, who was substantially well off himself, let it pass. There remains a family joke, which Elizabeth Lee retells with a wry smile: “Whenever someone comes up with an improvement for the chair,” she says, “We say, ‘Patent that.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/d0/48d0284f-4d0b-4d4c-abab-c8184fe441d9/adirondack_chair_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/35/4a35cd7c-af3f-48ef-83c3-fa9af53fa100/adirondack_chair_social.jpg)