An Airship The Size of a Football Field Could Revolutionize Travel

A new fuel-efficient airship, capable of carrying up to 50 tons, can stay aloft for weeks and land just about anywhere

:focal(988x80:989x81)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/cf/43cf2ef5-9e5d-41ff-958e-3624faf106ab/airlander.jpg)

Airships were, at one time, the future of air travel. During the 1920s and '30s, passengers and cargo weren't flown, but rather, airlifted to far off destinations. In fact, DULAG, the world's first passenger airline, operated airships that serviced more than 34,000 passengers and completed 1,500 flights prior to World War I.

Fastforward to today and there are some who believe that airships are poised for a revival. Among them is a UK design firm that recently unvieled the Airlander, a football field-sized aircraft engineered to push the limits of transportation. Unlike planes, it can take off vertically, from just about any locale. And unlike helicopters, it can carry a payload of 50 tons and stay afloat for weeks, long enough to circumvent the globe—twice, creators say.

The first thing the casual observer needs to know about the $40 million HAV 304 hybrid airship is that it's not a blimp. The sporting event staple is essentially a gargantuan inflatable balloon, but the Airlander is sturdier and easier to navigate. In a way, the aircraft is the kind of breakthrough aerospace engineers have been waiting for since the World War I era, when Zeppelins were used to transport passengers. But unlike those bygone relics, which used flammable hydrogen gas (remember the Hindenburg disaster?), the Airlander uses inert helium.

Up until the Hindenburg's explosion in 1937, America had been prepping infrastructure in anticipation of a future where the world's expanding fleet of dirigibles—lighter-than-air aircraft that rely on rudders and propellers—would dominate the skies, floating people and heavy cargo to almost any destination. The art deco spire atop the Empire State Building, for instance, was constructed as a docking terminal to load and unload passengers. And the U.S. government was so convinced airships were going to be the next big thing, officials even began stockpiling billions of liters of helium. (After realizing their prediction wasn't panning out, reserves of the lighter-than-air stuff were sold for more festive purposes, like party balloons).

Though the Airlander may be, oh, 70 years too late to that particular party, its technology still has the potential to revolutionize the aviation industry. For instance, the best efforts of aerospace companies to come up with a practical trans-oceanic, vertical take-off aircraft capable of lifting heavy cargo anytime, anywhere hasn't amounted to much beyond a couple multi-billion dollar military designs that probably, because of their incredible cost, will never be used commercially.

"There is a transport gap," explained Chris Daniels, Hybrid Air Vehicles' head of communications. "Even road vehicles need roads, and trains need tracks. Ships need water. Even airplanes need airports, and the more rugged cross-country vehicles struggle with some surfaces and aren’t amphibious, either. We need something that can land and take-off vertically, be robust enough to land on many surfaces, and have the range and affordability to travel long distances.”

The Airlander—all 44,000 pounds if it—was designed, from the bottom up, to fill this void. With a full tank of gas, it is expected to stay airborne and operational for as long as three weeks. To boot, the company also says the airship—easily the world's largest aircraft—uses 80 percent less fuel compared to conventional airplanes and helicopters, which should appease the environmentally-conscious set to some degree. This is made possible partly due to the ship's lightweight and semi-rigid hull, which is comprised of special leathery Kevlar material that's flexible, yet strong enough to withstand the impact of a shotgun bullet, Daniels says.

What's a bit surprising, though, is that the entire structure, when filled with helium, is actually heavier than air. While the weight ratio allows it to stay grounded without being tethered, only a small amount of forward speed is required to execute a take-off, thanks to unique wing-shape fins that give it an aerodynamic boost. The company estimates as much as 40 percent of the lift comes from the ship's aerodynamic design and propulsion system working in tandem.

Once aloft, the aircraft can reach a maximum speed of about 100 miles per hour. It lands with the help of vectored propulsors, or in layman's terms, thrusters that gradually push the ship downward, reducing lift by about 25 percent.

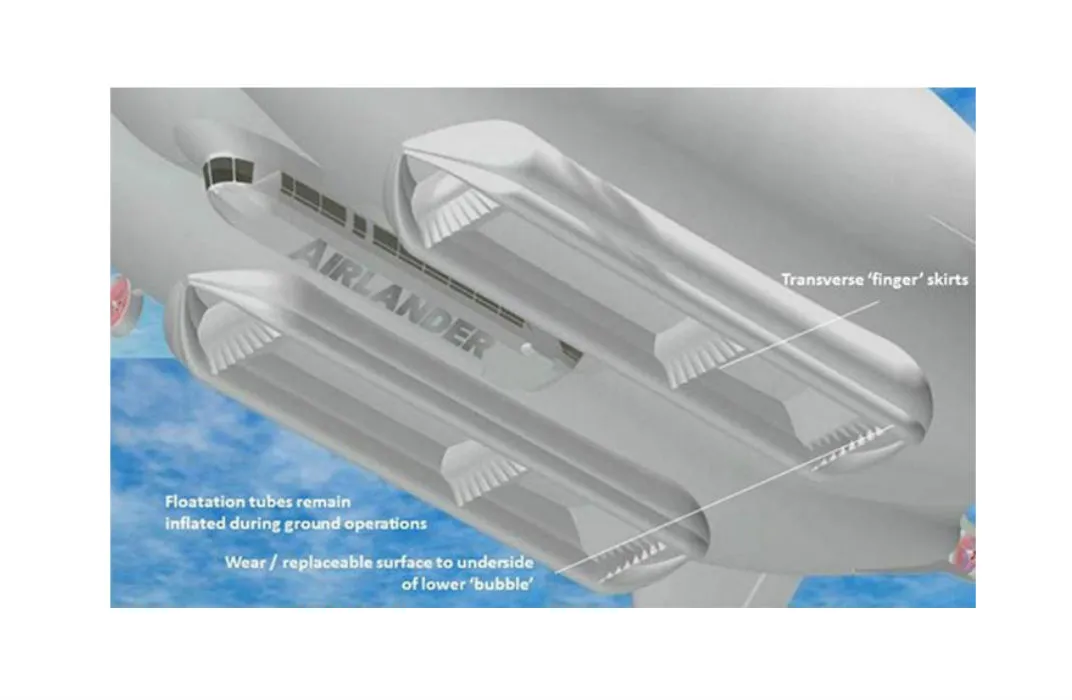

Beneath the aircraft, an air cushion landing system features amphibious pneumatic tubes that extend downward, enabling it to land just about anywhere. The Airlander, Daniels boasts, can vertically descend onto bodies of water, ice, desert and rugged terrains such as scrubland, making it especially ideal for delivering heavy equipment to remote oil and mining sites.

"The great thing about helium," he points out, "is that with each doubling in length of an airship, you get eight times the lifting capacity."

The original concept for the Airlander was so promising that, four years ago, the U.S. military decided to subsidize its development. However, the fate of the project took a turn. Budget cuts led to officials ultimately abandoning the idea, and the unfinished prototype was eventually sold back to Hybrid Air Vehicles for about $301,000—less than 1 percent of how much it cost to build.

Though the airship passed a flight test in August 2012 in Lakehurst, New Jersey, U.S. government officials determined it was still too heavy to be flown uninterrupted for more than a few days.

The next test flight, over the city of Bedford, New Jersey, is scheduled for December. The company, which was recently awarded a £2.5 million ($4.1 million) government grant to build upon its existing technology, also plans to develop different models that can aid delivery in disaster relief or be deployed in hard-to-reach places, such as icy roads close to Canadian mines.

While there's no target date for when such a model may exist—no companies have commissioned them yet—it isn't unrealistic to imagine the ships could also someday be piloted as an alternative to commercial air travel, which, in its current state, Daniels describes as an "unpleasant means to get somewhere desirable."

Among the most encouraging signs: Bruce Dickinson, lead singer of the rock band Iron Maiden, has since signed on as one of the project's principal financial backers. For a group in need of believers, having the "Futureal" frontman onboard isn't a bad start.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tuan-nguyen.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tuan-nguyen.jpg)