How Artificial Intelligence Can Change Higher Education

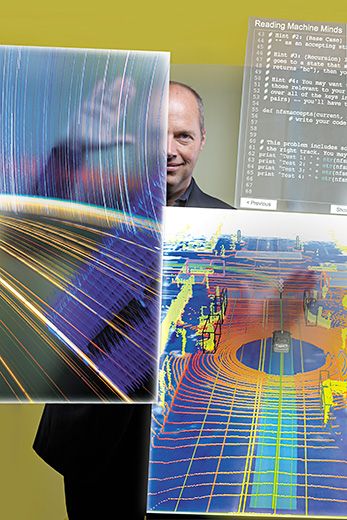

Sebastian Thrun, winner of the Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award for education takes is redefining the modern classroom

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ingenuity-Awards-Sebastian-Thrun-631.jpg)

On the day I met Sebastian Thrun in Palo Alto, the State of California legalized self-driving cars. Gov. Jerry Brown arrived at the Google campus in one of the company’s computer-controlled Priuses to sign the bill into law. “California is a big deal,” said Thrun, the founder of Google’s autonomous-car program, “because it tends to be hard to legislate here.”

He said it with typical understatement. An idea that was in its technological infancy a decade ago, when Thrun and his colleagues were racing to develop a vehicle that could drive itself more than a few miles on a desert test course, was now being officially sanctioned by the country’s most populous state. Thrun likes to quote Google’s Larry Page, whom he calls one of his mentors: “If you don’t think big, you don’t do big things. Whether it’s a big problem or a small problem, I spend the same amount of time on it—so I might as well take a big problem that really moves society forward.”

Thrun says this not on the sprawling Google campus, with its Mandarin language courses, haircut vans and Odwalla-stocked refrigerators, but in a cluttered conference room in a nondescript building on a busy commercial strip in Palo Alto. The office looks like Startup 101: fevered notation on whiteboards, Nerf blasters at employee workstations, a cornucopia of cereal boxes lining the break rooms, T-shirts with the company logo.

This is the headquarters of Udacity, billed as the “21st-century university,” where Thrun is taking his next big crack at the next big problem: education. While he still spends a day a week at Google, where he is a fellow, and remains an unpaid research professor at Stanford University (his wife, Petra Dierkes-Thrun, is a professor in comparative literature), Udacity is the place the 45-year-old, German-born roboticist calls home.

Udacity has its roots in the experience Thrun had in 2011 when he and Peter Norvig opened the course they were teaching at Stanford, “Introduction to Artificial Intelligence,” to the world via the Internet. “I was shocked by the number of responses,” he says. The class made the New York Times a few months later, and enrollment surged from 58,000 to 160,000. “I remember going to a Lady Gaga concert at the time and thinking, ‘I have more students in my class than you do in your concert,’ ” Thrun says. But it wasn’t just numbers, it was who was taking the class: “People wrote me these heartbreaking e-mails by the thousands. They were people from all walks of life—business people, high-school kids, retired people, people on dialysis.” Thrun, whose demeanor is a blend of continental sang-froid and Silicon Valley sunniness (he peppers the precise speech you might expect from a German roboticist with intensifiers like “super” and “insanely”), had a moment: “I realized, ‘Wow, I’m reaching people that really need my help.’ ”

The final spark came from a TED talk by the former hedge-fund analyst Salman Khan, whose Khan Academy videos—“201,849,203 lessons delivered”—offered instruction in everything from using trigonometric functions to Mark Rothko’s painting technique. “The thing that moved me,” Thrun recalls, “is that a single instructor could reach millions of people—and this wasn’t even a likely instructor, but a former financial guy.”

And so, with funding from Charles River Ventures, and with help from former Stanford AI colleagues like David Stavens, Thrun in February of this year launched Udacity, a startup providing what’s known as MOOCs: “massive open online courses.” Visit the web page udacity.com, and in just a few minutes you can be enrolled in Thrun’s Statistics 101, puzzling through questions of Bayesian probability—no tuition required. The courses, all free, are taught not only by academics, but also by Silicon Valley heavyweights like Reddit founder Steve Huffman and the serial entrepreneur Steve Blank. Companies like Nvidia and Google have signed on—not only as sponsors, but, potentially, as future employers of students who complete Udacity courses. After finishing a course, students can obtain a credential to show employers by taking, for a fee, an exam administered by the educational testing company Pearson VUE.

Thrun acknowledges that he’s a newcomer in an increasingly populated field. His former Stanford colleagues Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller have started Coursera, which partners with several dozen universities, while any number of universities have begun ramping up online offerings. MIT, which began placing material online a decade ago, recently partnered with Harvard University in edX. “The University of Phoenix has had a degree program since 1989,” Thrun notes. But as he sees it, online education needs new thinking—new ways of presenting information that maximize the Internet’s potential as a teaching medium. Cathy Davidson, a professor of English at Duke University and co-director of the MacArthur Foundation’s Digital Media and Learning Competition, sees Thrun’s enterprise as a catalyst for re-engineering online learning more broadly, citing his “tireless inventiveness and concern for the betterment of humanity.” She calls him “a true visionary” and adds, “which is to say, he’s a realist.”

Now, most MOOCs consist essentially of lectures posted on the Internet—“very boring and uninspirational,” Thrun says. He compares the situation to the dawn of any medium, such as film. “The first full feature movies were recordings of the physical play, end to end. They hadn’t even realized you could make gaps and cut the movie afterwards.” Udacity is rewriting the script: Rather than a talking head, there’s Thrun’s hand, writing on a whiteboard (“The hand came along by accident,” he says, “but people loved it”); rather than a quiz a week later, the lesson is peppered with on-the-spot problem-solving. What sets Udacity apart from traditional educational institutions—and from its online predecessors—is this emphasis on identifying and solving problems. “I firmly believe that learning occurs when people think and work,” Thrun says. Udacity’s website says, “It’s not about grades. It’s about mastery.” One satisfied student wrote that Udacity had defined the difference between putting a university course online and creating an online university course.

Just as Thrun speaks with conviction about the larger social import behind the gee-whiz technology of autonomous cars—“You can save lives, you can change what cities look like, you can help people share cars, you can help blind and elderly people”—he is passionate about the larger promise of Udacity. There are over 470,000 students waiting to get into community colleges in California alone. “The government doesn’t have the funds to cover their expenses,” Thrun says. “Education is really in a crisis.”

With Udacity, he says, he also wants to make education accessible to people with jobs, kids, mortgages. On the whiteboard table, he starts writing. “If you look at how life is arranged,” he says, “right now it’s play, then K-12 learn, all the way to higher ed, then it’s work, then it’s rest. These are our phases, they’re sequential. I want it to look like this,” he says, jotting a flurry of words so that “learn” is under “work” and “rest.” Why do we give up learning after college? And why, he asks, do universities give up teaching their students when they leave? “My HMO gives me a lifetime deal if I want, so why not my university?”

MOOCs offer the potential to make higher education more available, more affordable and more responsive to employers’ needs than traditional university degrees. But will they help inaugurate an “Athens-like renaissance” in education, as former Secretary of Education William Bennett has suggested? Coursera’s Ng says that online education may influence, rather than replace, traditional universities. “Content is increasingly free on the web, whether we like it or not,” he says. What MOOCs augur, he says, is the so-called “flipped classroom,” in which students watch classes online the week before and come to class “not to be lectured at,” but to actively engage.

Thrun believes online education is at the same sort of transitional moment self-driving cars were a decade ago—a moment that plays to his own problem-identifying strengths. Chris Urmson, the engineering head of Google’s self-driving car program, describes Thrun as someone “who has the insight to see when something needs to happen” but “isn’t purely visionary—he has the drive and execution to go and actually do it. Seeing the two mix in one person is rare.” (Thrun’s dual nature might be seen in the cars he drives: a Chevy Volt, the quintessence of quiet, left-brained efficiency, and a Porsche, that splashy emblem of ego, adventure and risk.) And Udacity speaks to another Thrun obsession: “For me, scale has always been a fascination—how to make something small large. I think that’s often where problems lie in society—take a good idea and make it scale to many people.”

***

Long before he was trying to tackle large, complex problems, Thrun tackled small, complex problems as a teenager in a small town near Hanover, Germany. On a Northstar Horizon computer, a gift from his parents, he tried writing a program to solve Rubik’s cube. Another program, to play the board game peg solitaire, involved what’s known in math as an “NP-hard problem”—at each step the time-to-solve grows exponentially. “I started the program, waited a week, it didn’t make any progress,” he says. “I realized, wow, there’s something profound, deep, that I don’t understand—that a program could run for millennia. As a high-school student, it’s not in your conception.”

At the University of Bonn, Thrun studied machine learning, but dabbled in psychology—“My passion at the time was people, understanding human intelligence.” In 1991, he spent a year at Carnegie Mellon under the tutelage of the AI pioneers Herbert Simon and Allen Newell, building small robots and testing his theories about machine learning. But even then, he was thinking beyond the lab. “I always wanted to make robots really smart, so smart that I wouldn’t just impress my immediate scientific peers, but where they could really help people in society,” he says.

He actually became an adjunct professor of nursing while developing robotic nurses at a Pittsburgh elderly-care home. Another early effort, a robot named Minerva, was a “tour guide” that welcomed visitors to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. It was, says Thrun, a learning experience. “What happens if you actually put a robot among people? We found problems we never actually anticipated.” Visitors, for example, tried to test the robot’s ability. “At some point, people lined up like a wall, and hoped the robot would drive into an area where it didn’t know how to operate, like a nearby cafeteria,” he says. “And the robot did.”

In 2001, Thrun went to Stanford, where the Silicon Valley spirit hit him like a revelation. “In Germany there’s just many questions you’re not allowed to ask,” he says, “and for me, the core of innovation is for very smart people to ask questions.” In the United States, and particularly Silicon Valley, he found an “unbelievable desire” to ask questions, “where you don’t just go and proclaim something because it’s always been this way.” He wishes, he says, “that Silicon Valley wasn’t 2,500 miles away from Washington, D.C.,” that societal innovation could keep up with technical innovation. “We can’t regulate our way out of problems,” he argues, “we need to innovate our way out.”

It was in that spirit that he plunged into work on an early version of the car that would eventually make its way to Google. In 2007, he took a year’s leave from Stanford to help develop Streetview, Google’s 360-degree mapping feature. “It became an amazing operation, the biggest photographic database ever built at the time.” Then he assembled an AI dream team to make the self-driving car a reality (a version named Stanley, which won the 2005 DARPA Grand Challenge for driverless vehicles, is held by the American History Museum) and founded Google X as a skunkworks for developing products like the augmented-reality “Google glasses.”

Udacity may seem rather a departure for Thrun, but Urmson, his Google colleague, says that while it’s different on a “purely technical axis,” it shares with his other work the “opportunity to have this transformative impact.” There are other parallels. Thrun seems intent on hacking education the same way he hacked driving, drilling it down to its component parts, testing and retesting. “We do a lot of A/B testing,” he says, describing the technique, popular in Silicon Valley, for comparing two different versions of a web page to see which is more effective. “We have lots of data. We use it strictly for improving the product.” (He jokes that he even runs scientific tests on his 4-year-old son: “I gave him infinite access to candy the first day; the second, suddenly he didn’t like it anymore.”)

In his statistics course, he occasionally puts out some theorems that are “way too hard.” But he wants to see how many people will make the effort (60 percent, it turns out). While some have complained that his courses are too easy because they give students an endless number of chances, he says he’s inspired by Khan’s notion that different students learn at different speeds. “In the beginning, I was the typical professor, saying you get exactly one chance,” he says. “A lot of students complained: ‘Why do you do this? Why do you deprive at the moment where I’m actually succeeding?’”

This time, he realizes, he may be the one getting it wrong. “We’re starting from scratch,” he says. “I’m the first one to realize we haven’t figured out how to do it right. We really have to be humble and realize that it’s just the beginning.” He wants to redress “this bizarre imbalance” in education “between the value paid and the services rendered.”

As Norvig argues, “This idea that you go to school for four years and then you’re done—that’s not going to cut it. Ten years from now you’re going to be doing something that you weren’t trained in in college because it’s not a career that existed ten years ago. So you’re going to need continual training.” He now teaches at Udacity.

At Google Thrun had the latitude and money to work on projects like Streetview, where “you couldn’t really tell what it was good for, other than that it was kind of cool,” he says. His investment in Udacity is more personal. He likes to quote Regina Dugan, former head of DARPA: “What would you do if you knew you couldn’t fail?”