How Do You Get Poor Kids to Apply to Great Colleges?

Caroline Hoxby and her team of researchers are revolutionizing the way the best colleges reach out to talented low-income students

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hoxby-ingenuity-portrait-631.jpg)

Sometimes, late at night, you stare out your window at the black Nebraska sky and wonder if you really are a freak like everyone at school says. It’s not just the pile of Jane Austens under your bed that you’ve read till the pages are ragged or the A’s you’ve racked up in everything from chemistry to AP history. It’s your stubborn belief that there’s more out there than homecoming, keggers and road trips to the mall 80 miles away in Lincoln. Your mom is sympathetic but between cleaning floors at the nursing home and taking care of your little brothers, she has even less time than she has money. Your dad? Last you heard, he was driving a forklift at a Hy-Vee in Kansas City.

You scored 2150 on your SATs, highest anyone around here remembers, so it will be easy to get into the state school a couple of towns away. But maybe you’ll go to the community college close by so you can save a little money and help your mom out—and it would save having to take out loans to pay for tuition. Pretty much everyone winds up dropping out eventually anyway. By the time you’re 19 or 20, it’s time to start bringing home a paycheck, earn your keep.

Then, on a balmy afternoon, you come home from school, toss your backpack on the kitchen table, and see that a thick packet has come in the mail. You don’t know it yet, but what’s inside will change your life.

You open the envelope and find a personalized letter from the College Board, the SAT people. It says that, because your grades and scores are in the top 10 percent of test takers in the nation, there are colleges asking you to apply. Princeton, Harvard, Emory, Smith—there’s a long list, places you’ve read about in books. And here’s an even more shocking page: It says the College Board somehow knows your mom can’t afford to pay for your schooling so it will be free. There’s even a chart comparing costs to these schools and your community college and the state campus, breaking them down in black and white—it turns out your mom would have to pay more to send you to the community college than to Princeton or Harvard. To top it all off, clipped to the packet are eight no-cost vouchers to cover your application fees!

You sit at the table, stunned. Could this be true? No one you’ve ever known has even gone to a top-tier college. Blood rushes to your head and you feel a little faint as the thought takes over your brain: You could do this. You could really do this. You could be the first.

***

“The amount of untapped talent out there is staggering,” says Caroline Hoxby, the woman who created that magic packet, as she sits in her office on the Stanford campus, a thousand miles away, in every way, from that small Nebraska town. (The privacy of participants is fiercely protected, so the girl and the town are composites.) Dressed in her usual uniform, a sleek suit jacket and slacks, with her hair pulled back tightly and small earrings dangling, she radiates intensity. A Harvard grad, she's married to Blair Hoxby, an English professor at Stanford.

The information packet, which grew out of two landmark studies she published in the last year, is the crowning achievement of her two decades as the country’s leading educational economist. This September, her idea was rolled out nationally by the College Board, the group that administers the SAT. Now, every qualified student in the nation receives that packet. In a world where poverty and inequality seem intractable, this may be one problem on the way to being solved.

“It can take a generation to make a fundamental change like this,” says William Fitzsimmons, director of admissions at Harvard. “What Caroline has done will leapfrog us ahead.”

***

It was an unsettling experience at Harvard that spurred Hoxby to study the students she now is obsessed with helping. In the summer of 2004, then-president Lawrence Summers and his brain trust were frustrated that the school was still largely a place for the affluent. Despite the fact that low-income students had long had virtually a free ride, only 7 percent of the class was coming from the bottom quartile of income, while nearly a third came from families earning more than $150,000 a year. So the school announced to much fanfare that it would officially be free for those with less than $40,000 in annual family income (now up to $65,000). No loans, just grants to cover the entire cost. The administration figured the program would instantly flush out superstar high-school seniors from unexpected places—hardscrabble Midwestern farming communities, crime-pocked cities too small for a recruiter to visit, maybe even a small Nebraska town where a girl with straight A’s seemed destined to languish in her local community college.

But when April rolled around, there was nothing to celebrate. The number of incoming freshmen with family incomes below $40,000 was virtually flat, fewer than 90 in a class of 1,500, a tiny bump of only 15 or so students. Other elite institutions that had quickly matched Harvard’s program reported even more depressing statistics.

So Hoxby, who was on the faculty at the time, began to analyze what had gone wrong. A former Rhodes scholar with a PhD from MIT, she had almost single-handedly created the field of educational economics. Her previous work had measured whether charter schools raise student achievement, whether class size really mattered and how school vouchers worked.

The problem captured her immediately. She had analyzed the data enough to know that many qualified low-income students were not applying to selective schools. While Harvard could afford to step up its expensive outreach—in recent years it and other top schools have increased the proportion of low-income students to as much as 20 percent—Hoxby estimated that there were huge swaths of kids who were being overlooked.

“Caroline,” says Harvard’s Fitzsimmons, “has a great heart as well as a great intellect. And like every economist, she hates waste, especially a waste of human capital.”

First she had to figure out how many qualified students were actually out there—and where. The College Board and its counterpart, the ACT, which administers another admissions test, knew who had high scores, but not who was poor. Test-takers are asked about family income, but only about 38 percent respond, and, as Hoxby says, “lots of kids have no idea what their parents make.” Colleges glance at application ZIP codes, but that’s a blunt instrument, especially in vast rural areas. Ironically, “need-blind” admissions, used by about 60 top schools, had contributed to the dearth of information. The policy, instituted to make sure the process didn’t favor wealthy students, precludes schools from asking applicants about their household income.

So Hoxby, 47, and co-author Christopher Avery, a public policy professor at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, tackled a monumental data challenge. They decided to look at every senior in the U.S. in a single year (2008). They devised a complicated set of cross-references, using block-by-block census tract data. They matched each student with an in-depth description of his or her neighborhood, by race, gender and age, and calculated the value of every student’s house. Parents’ employment, education and IRS income data from zip codes were also part of the mix. They even tracked the students’ behavior in applying to college.

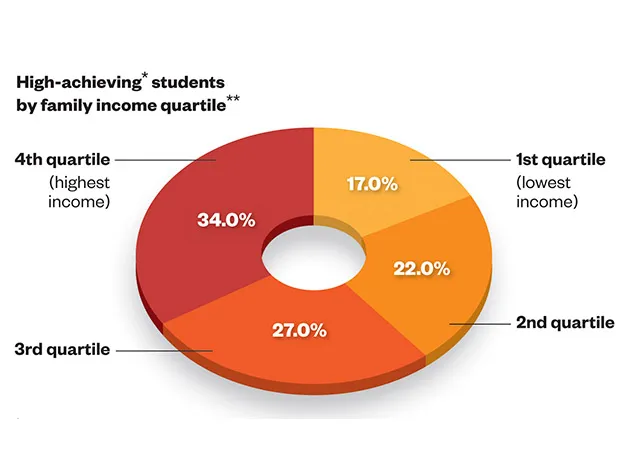

The results were shocking. They found approximately 35,000 low-income kids with scores and grades in the top 10 percentile—and discovered that more than 80 percent of them didn’t apply to a single selective institution. In fact, a huge proportion applied to only one college, generally a non-selective school that required only a high-school diploma or a GED, and where a typical student had below-average scores and grades.

Mostly from rural backgrounds, crumbling industrial outposts or vast exurbs, these students had been falling through the cracks for generations. Elite institutions traditionally concentrated on a small number of cities and high schools in densely populated, high-poverty areas, places that had reliably produced talented low-income students in the past. Smaller markets, such as Nashville, Topeka and Abilene, rarely got a look. Kids in rural settings were even less likely to catch the eye of college admissions staff, especially with college counselors an endangered species—the ratio of counselors to students nationally is 333 to one.

“When you’re in admissions, you go to the schools that you know, to areas likely to have a number of kids like that,” says Hoxby. “You might have a school in New York, for instance, that has a really great English teacher whose judgment you trust. You work your contacts, just like in everything else.”

Hoxby realized it wasn’t practical to expect colleges to try to locate these kids. She had to find a way to motivate the students themselves to take action. Getting the usual “think about applying” form letter from, say, Haverford or Cornell, wasn’t doing the trick. Low-income students and their parents were dismissive of such prompts, seeing them as confusing and meaningless. While some students chose a local school because they didn’t want to leave home, others were deterred by the sticker price. With all the hoopla about rising college costs, they assumed that a fancy private education would be far out of their range. Just the cost of applying to schools—often $75 per shot—was often prohibitive.

While creating the packet, Hoxby and a second co-author, economist Sarah Turner of the University of Virginia, found that small tweaks made a huge difference. With the help of graphic designers, they fiddled with everything from the photos to the language, the fonts and the ink color. They also tested which family member should get the packet (parents, students or both). “There I was, discussing whether or not we should use 16-point type in a particular headline,” she recalls. “It’s not the usual thing for an economist to be doing.”

The packets are tailored for each student, with local options and net costs calculated and compared, apples to apples. It’s a process Hoxby likens to Amazon’s algorithms. “You know how when you log in you see things that are just for you? It looks very simple, but the back office is actually massively complicated. If everyone just saw the same thing, randomly, we’d never buy anything.”

In the end, students who got the packet during the two years of her study—2010 to 2012—started acting more like their affluent peers. They applied to many more colleges, and were accepted at rates as high as Hoxby estimated they would be. For $6 apiece, she likely changed the course of thousands of lives—as well as the future of the ivory tower.

“We will do anything we can to make sure that people who qualify for an education of this caliber can have one,” says Michael Roth, president of Wesleyan.

The Supreme Court has begun to weaken the case for race-based preferences, and Hoxby—whose father, Steven Minter, former under-secretary of education under Jimmy Carter, is black—often gets asked if her studies herald a new era of

class-based affirmative action. It’s a policy that would put poor rural kids, who are often white, on the same footing as inner-city students, who are almost always of color.

Such questions clearly annoy her. “What people need to understand is that this is not affirmative action. These kids are just as qualified as their privileged counterparts in terms of their grades and scores. They graduate those colleges at the same rate. No requirements are being bent. The issue is just finding them.”

Even so, Hoxby’s work has sparked discussions about economic affirmative action. Currently few if any schools give weight to applications from low-income students, though some do look at whether an applicant is the first in the family to go to college.

That may soon change, says Maria Laskaris, dean of admissions at Dartmouth. But giving greater preference to low-income applicants could spark blow-back from upper-middle-class families. “If we decide to take more of any sort of student, others don’t make it in. It’s challenging,” she says.

While schools such as Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth can provide full aid to more low-income students, schools with smaller endowments could find it hard to finance a new wave of need. In a recent letter to the New York Times, Catharine Hill, president of Vassar, applauded the College Board’s intentions but cautioned that the intervention that Hoxby engineered “will indeed create tensions surrounding financial aid” at the more than 150 top institutions that cannot afford to be need-blind.

Hoxby responds to such fears with her usual mixture of iron will and confidence, softened by a rueful laugh. “Schools have no reason to be afraid. It’s not going to happen overnight; there isn’t going to be a sudden flood. That isn’t the way the world works. It takes time. The information will spread gradually over the next few years. In the meantime, colleges will find a way to do this. They have to,” she concludes. “We have to."