How the Escalator Forever Changed Our Sense of Space

Sure, the 19th-century invention transformed shopping. But it also revolutionized how we think about the built environment

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/4e/ab4e82ac-55c6-4875-93f4-6b89ca8012b1/dupont_circle_escalator.jpg)

Great technological developments create a universe. The invention of the escalator was, literally, ground-breaking. It expanded our concept of space and time—and, accordingly, redefined the possibilities for commerce.

For those within the intellectual property system, the escalator is famous for its association with “trademark genericide.” Genericide occurs when trademarks become so famous that they cease to identify the source of goods or services in the minds of consumers and instead become names for the goods themselves. “Escalator” is right up there with “aspirin,” “cellophane,” and “kitty litter” as an example of a brand that morphed into its product. And it’s true that the intellectual property story of the escalator is, in part, how Charles Seeberger’s brand of moving staircases grew to symbolize the thing itself. But the larger story is about the cultural phenomenon, an invention that transformed the way we interact with the world. How people move. How sales are made. How the built world is constructed.

Before the escalator was invented, commerce and transportation were largely one-dimensional. Stairs and elevators were for the committed and purposeful, their limitations constraining vertical expansion, above and below ground. Stairs require patience and effort. Elevators have a unique, precise, and tightly constrained mission. The invention of the escalator changed everything: suddenly, a constant flow of people could ascend into the air, or descend to the depths. The escalator modified architecture itself, creating fluid transitions into spaces above and below. Now, in commerce and transportation, neither the sky nor the ground would be the limit.

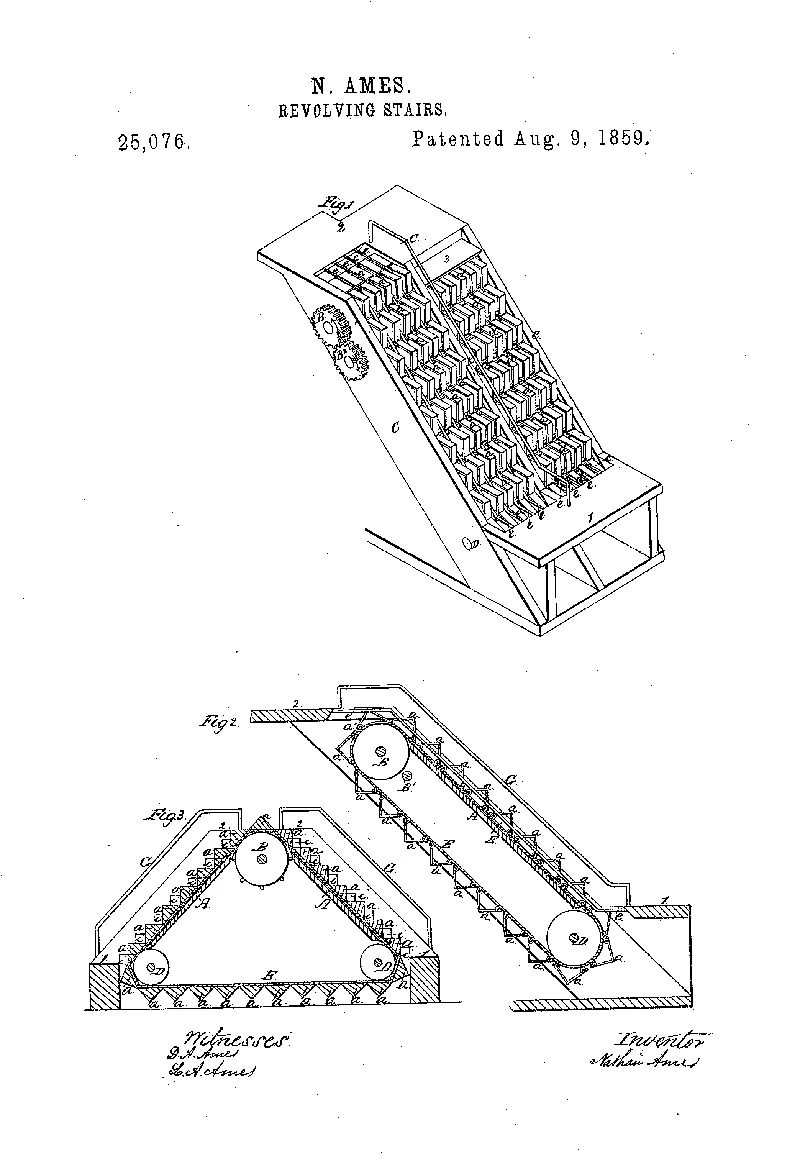

The first conceptual articulation of an escalator was “An Improvement in Stairs,” described in an 1859 U.S. patent issued to Nathan Ames. Ames was an inventor with several patents, including a railroad switch, a printing press, and a combination knife, fork, and spoon. Ames’ patent made claim over an endless belt of steps revolving around three mechanical wheels that could be powered by hand, weights, or steam. This version of the moving stairway didn’t gain much momentum, however, and was never built.

As the 20th century drew near, urbanization transformed society, and the development of the escalator was inextricably connected with the new way that people were living and working. Architecture responded to increasing populations in cities through the development of skyscrapers, department stores, and urban planning. Mass transit facilitated movement via electric streetcars, elevated trains, and the promise of subway systems. Revolutions in printing and photography heralded an explosion of advertising and new ways to sell goods.

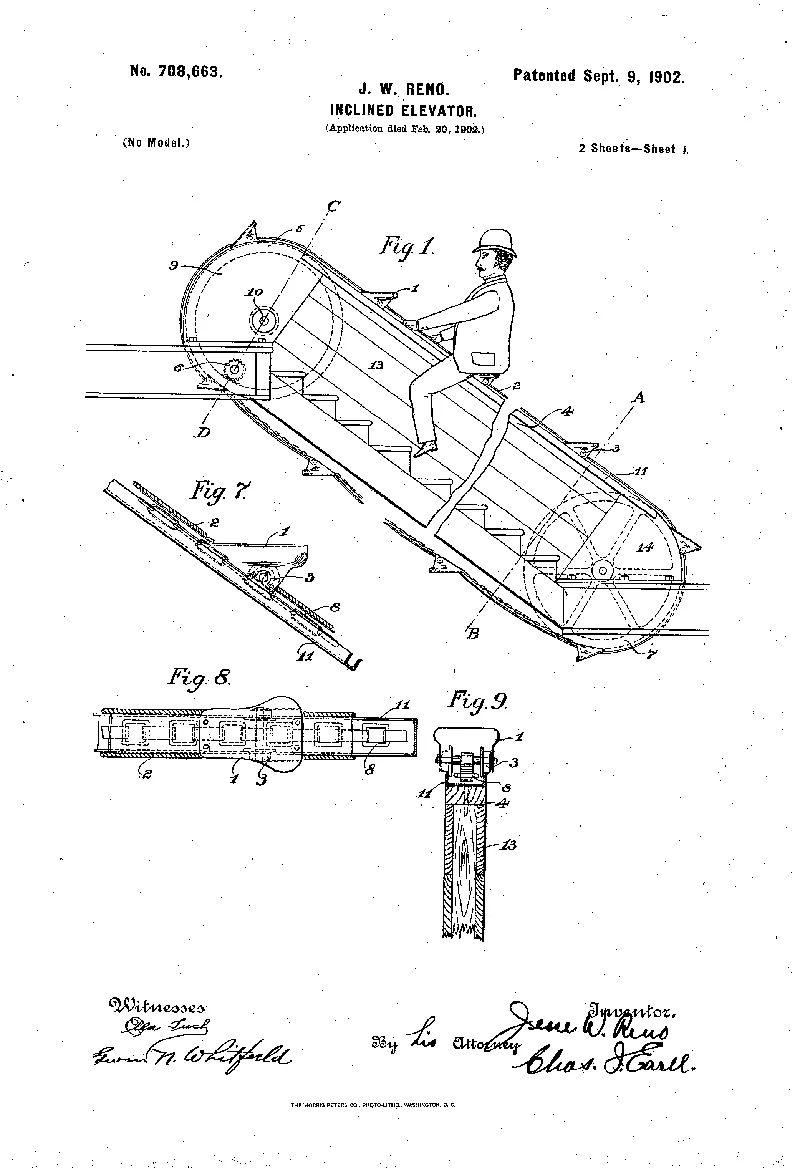

These cultural and economic developments coincided with the most important technological improvement in the moving staircase: the use of a linear belt, invented by Jesse Reno. Reno was an engineer, working at the time on a plan for a subway system in New York City, involving slanted conveyors to move passengers underground. After the city declined to adopt his plan, he focused instead on the technology. Granted a patent in 1892 over an “Inclined Elevator,” he demonstrated the design at Coney Island in 1896: riding his invention, passengers leaned forward and stood on a conveyor belt of parallel cast-iron strips, powered by a concealed electric motor. During two weeks at Coney Island, 75,000 people were elevated seven feet. It was a sensation. Building on this success, a Reno Inclined Elevator was installed at the Brooklyn Bridge the following year.

A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects

What do the Mona Lisa, the light bulb, and a Lego brick have in common? The answer - intellectual property (IP) - may be surprising. In this lustrous collection, Claudy Op den Kamp and Dan Hunter have brought together a group of contributors - drawn from around the globe in fields including law, history, sociology, science and technology, media, and even horticulture - to tell a history of IP in 50 objects.

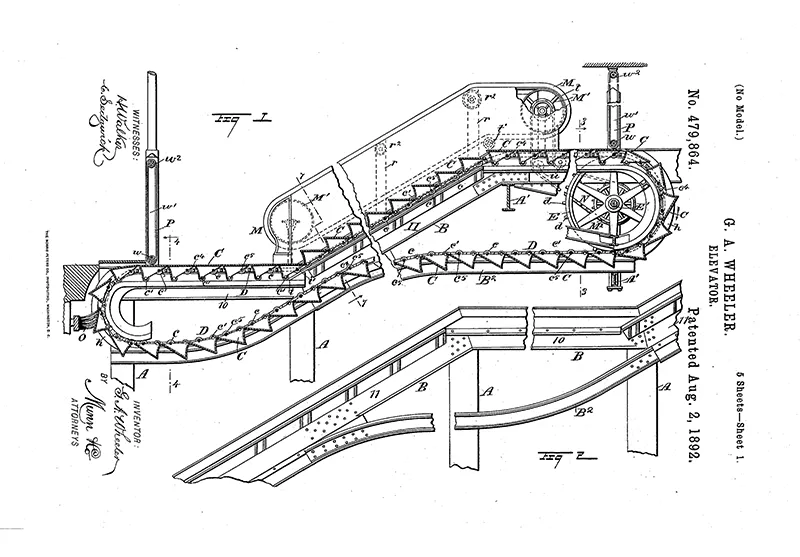

As so often happens when cultural movements and technological innovation intersect, another inventor contemporaneously created a different version of the moving staircase. George Wheeler’s “Elevator” was similar to what we know as the modern escalator, and it was the one that took hold in the market. It comprised steps that emerged from the floor and flattened at the end. Wheeler’s patents were purchased by Charles Seeberger in 1899, who quickly struck a deal with elevator manufacturer Otis to produce moving staircases. Seeberger also coined the term “escalator”—from the French “l’escalade”, to signify climbing—and registered the trademark ESCALATOR (US Reg. No. 34,724).

The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping notes that the escalator is among the most important innovations in retail marketing, remarking that no invention has had more impact on shopping. It’s not hard to see why. The elevator can transport a small number of people between floors. The stairway is constrained by the effort and commitment it requires from consumers to move between floors. But the moving staircase democratizes all levels; upper floors become indistinguishable from lower. Retail traffic flows seamlessly between levels, so that the consumers can access higher floors with little more effort than entering on the first floor. The Siegel Cooper Department Store in New York was the first to recognize its revolutionary potential, installing four of Reno’s inclined elevators in 1896.

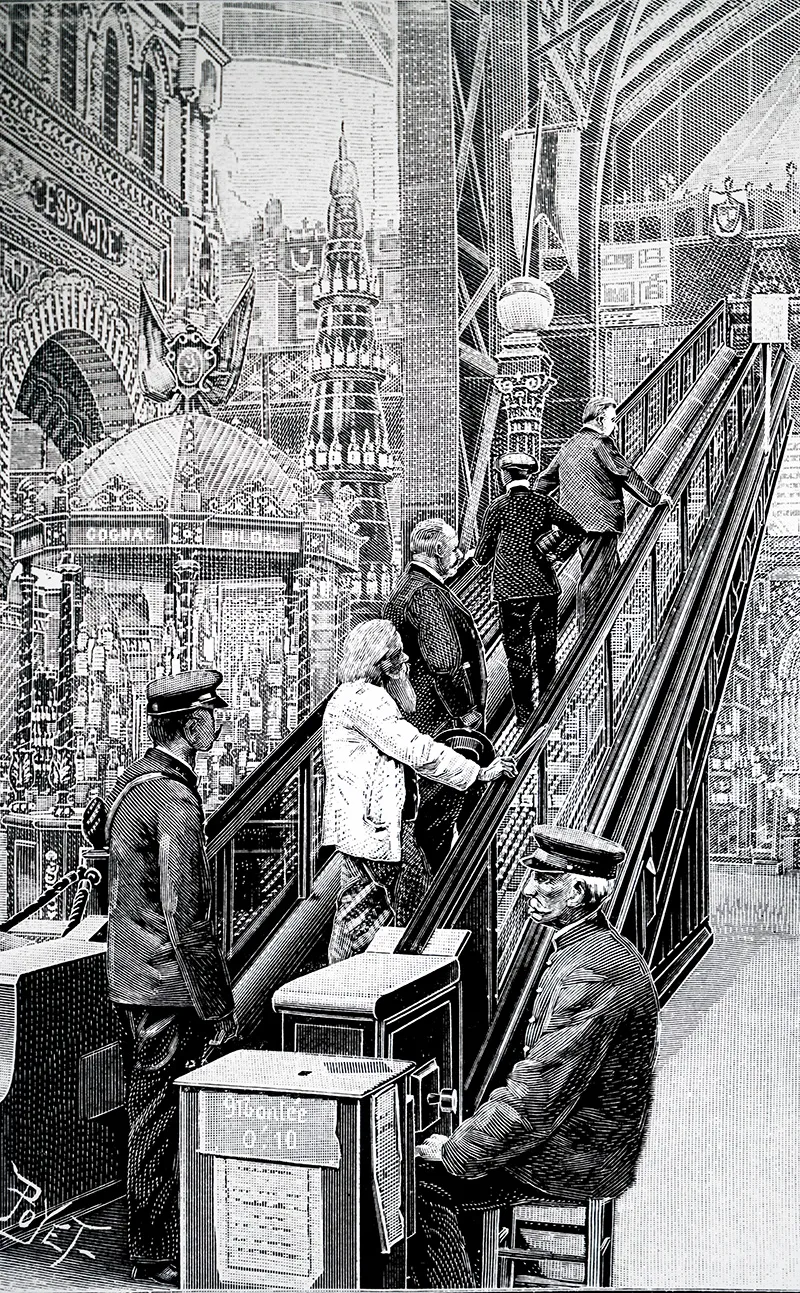

A universe of possibility opened when moving staircases were introduced to the world at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900. The World’s Fair long served as the place where innovators demonstrated breakthrough technologies on the world stage—the show introduced the world to the Colt revolver (London, 1851), the calculator (London, 1862), the gas-powered automobile (Paris, 1889), the Ferris Wheel (Chicago 1893), the ice cream cone (St. Louis, 1904), and both atomic energy and television (San Francisco, 1939).

The Paris Exposition of 1900, in particular, has been called one of the most important of them all. At the time, though, organizers and government officials were concerned how this Exposition would make its mark—after the introduction of the Eiffel Tower at the fair in 1889, how could the one 11 years later compete? Officials entertained many bizarre proposals, many of which involved alterations of the Eiffel Tower itself including the potential additions of clocks, sphinxes, terrestrial globes, and a 450-foot statue of a woman with eyes made from powerful searchlights to scan the 562-acre fairgrounds. Instead, rather than beams of light from a giantess, what shone brightest at the 1900 Paris Exposition was the moving staircase. It won Grand Prize and a Gold Medal for its unique and functional design.

After the Exposition the invention spread internationally. Bloomingdale’s in New York removed its staircase and installed an inclined elevator in 1900. Macy’s followed suit in 1902. The Bon Marché in Paris installed the European “Fahrtreppe” in 1906. Escalators made department stores commercially viable entities in ways that stairs and the elevator simply could not. Vertical expansion of the stores into upper levels was now as viable as horizontal expansion, but at a fraction of the cost.

The escalator did not simply revolutionize the shopping experience through vertical movement; it also created a new universe of human activity. Escalators transformed public transportation when they were installed in underground railway stations in New York and London in the early 1900s. In 1910, the Boston Sunday Globe included a series of illustrated comics providing a caricature of human behavior on the escalator, including “The Timid Lady Who Keeps the Crowd Waiting,” and “They [Who] Are Unable to Pass the Stout Party.” The newspaper noted that the “sport of escalating” is “a simple thing when you know how” but could fool “many an agile man.”

Within the workplace, the changes were equally revolutionary: throughout the first half of the 20th century, escalators quickly became a tool of workplace efficiency. They enabled rapid transition between shifts, and were installed by owners to maximize efficiency for workers on a two- to three-shift system. Yet the benefit to the workers was real, and, from mills in Massachusetts to the factories of the Soviet Union, escalators were often adopted as a potent symbol of the proletariat.

With post-World War II prosperity and a renewed hunger for shopping in the United States, the escalator found an expanded market. An Otis advertisement at the time captured the spirit of the moment, when “the Escalator polished up its manners, put on a new dress of gleaming metal in the latest streamline fashion, and went out in quest of new jobs.” Otis marketed directly to consumers, and its advertising was widely recognized and very successful: an “Advertising Times” columnist of the day wrote of the triumph of the Otis marketing strategy, and the wisdom that the company had shown recognizing the power of “straight out-and-out advertising.”

Ironically, Otis’ marketing success in making its escalator a household name cost the company one of its most important assets. In 1950 its competitor, the Haughton Elevator Company, petitioned the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to cancel the ESCALATOR trademark, on the basis that the term had become generic to engineers, architects, and the general public. In court, Otis’ ads were used against the company—one ad described “The Meaning of the Otis Trademark” in the following terms:

To the millions of daily passengers on the Otis elevators and escalators, the Otis trademark or name plate means safe, convenient, energy-saving transportation… To thousands of building owners and managers, the Otis trademark means the utmost in safe, efficient economical elevator and escalator operation.

The USPTO found that the advertisements showed that Otis treated the term “escalator” in the same generic and descriptive way as the term “elevator.” The mark no longer represented the source of the product; it represented the product itself. Consequently, the mark was canceled—and to this day when you think of the word “escalator” you are unlikely to call to mind the Otis company.

The modern market for escalators has increased dramatically. As cities around the world increase in density, they often rely on the escalator as a key architectural element, both above and below ground. In Hong Kong the Central Mid-Levels Escalators span an entire hillside—a 2,625-foot set of moving sidewalks lined by open-air markets, stores, and apartment towers. The number of escalators in the world doubles every ten years: Otis continues to be a major player, although by 1993 its nemesis, the Haughton Elevator Company (now owned by Schindler) claimed to have the largest market share of escalators. Yet, amazingly, the basic form of these new escalators has barely changed from the design sketched out in the early Wheeler patents.

The revolutionary has become ordinary, and escalators are now simply part of the background cultural radiation of modern life. Movies are replete with escalator scenes, from An American Werewolf in London, to Rain Man, to The Hangover’s parody of the Rain Man escalator scene. Perhaps the movie Elf best encapsulates our relationship with the escalator. In that movie, Will Farrell plays a human raised by elves, who visits New York City to find his biological father. Alien to modern technology, he does not know how to step on an escalator at a department store and, after several aborted attempts that interrupt the flow of traffic and irritate those around him, he steps on with one foot, holding onto the rails with his arms. His front foot escalates while the rest of him drags behind. The scene is a reminder of the strange wonder that is the escalator; one we now take for granted. It could be a scene by Buster Keaton, or drawn from the 1910 Boston Sunday Globe comic: “Man Who Forgets to Step with Both Feet.” The scene is funny precisely because it calls up both the marvel and banality of the moving staircase.

We take the escalator for granted, in part, because it is that possibility realized; we all now inhabit the world of the escalator, with no longer a sense of its radical nature. The escalator may be the most important invention in shopping, but its impact reaches well beyond commerce. It has conquered space itself.

From the forthcoming book: A HISTORY OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY IN 50 OBJECTS edited by Claudy Op den Kamp and Dan Hunter. Published by arrangement with Cambridge University Press. Copyright © 2019 Cambridge University Press.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.