How Farms Became the New Hot Suburb

A new real estate trend has developments planted around working farms. But are these communities sustainable?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/f5/e9f5efc4-a3ed-4509-bd9d-9c350214d217/may2015_c06_farmtopia.jpg)

At the cusp of the Great Depression, the humorist S.J. Perelman and his wife moved from Manhattan to a farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Fifteen years of rusticating left him with “a superb library of mortgages, mostly first editions, and the finest case of sacroiliac known to science.’’ Perelman recounted his picturesque miseries as a country squire in the 1947 collection Acres and Pains, which introduced readers to his real estate agent (Dewey Naïveté), his attorney (Newmown Hay, of Ashen, Livid & Hay) and his farm (Rising Gorge), which he describes as “an irregular patch of nettles bounded by short-term notes containing a fool and his wife who didn’t know enough to stay in the city.”

Perelman’s rueful tale gained its widest cultural currency when it was adapted into the 1960s sitcom “Green Acres,” about a New York lawyer who pines for a simpler life, and, over the objections of his socialite wife, buys a farm, sight unseen. His own dewy naiveté was neatly summed up in the theme song: Green Acres is the place to be / Farm livin’ is the life for me / Land spreadin’ out so far and wide / Keep Manhattan, just give me that countryside.

Possibly the most enthusiastic embrace of farm livin’ these days is found deep in the woods of Chattahoochee Hill Country, southwest of Atlanta. There lies Serenbe, a 1,000-acre suburban Eden comprising two neighborhoods (and counting) bunched around Ye Olde English village-style town centers. The hamlets are shaped like omegas to conform to the undulations of the land. Peach and pecan trees shoot up from the sidewalks; goats and llamas browse in dells; and lambs caper along the walking trails that curl through glens and glades.

Everything has been assiduously planned. Cottages and co-ops are built to energy-efficient EarthCraft specs. Waste water is filtered in a biological treatment system and reused for irrigation. The town centers are dotted with upmarket galleries, and a nonprofit cultural institute stages plays and sponsors artists in residence. There are stables, spas and, not least, a farm that produces 350 varieties of organic fruit, vegetables, herbs and flowers.

“When I first visited here, I thought Serenbe felt artificial,” says E.C. Hall, a resident and retired college professor. “I thought of the prefabricated town in The Truman Show, created to exist separately from the rest of the world. That changed when I walked around and met people every few yards. I realized we all had a similar desire for community.”

Serenbe is perhaps the country’s most popular and profitable “agritopia,” the leafiest, farmiest of all the nascent trends in real estate, in which agrarian-focused housing schemes are anchored by farmland rather than, say, greenswards, man-made lakes or golf courses. Ranches, gardens and vineyards are major selling points. There are already dozens of agritopian developments and, fueled by the local-food movement, emerging widespread environmental consciousness, Perelmanesque romanticism and good old American marketing chutzpah, more are in the works—enough to qualify as a trend in America’s preeminent rural community paper, the New York Times.

Agritopias are popping up like dandelions across the country, and why not? Developers are nothing if not attuned to their customers, and what the customers want is increasingly clear. At Serenbe, that’s eight acres of farmland, which produce enough veggies to supply a half-dozen restaurants (three onsite), a farmer’s market and a Community-Supported Agriculture program with 120 members (most of whom live in outlying towns).

“The thing I like about the farm is that it’s as real as any I’ve ever worked on,” says Serenbe resident Rebecca Williams, a 31-year-old Atlanta native who worked at a variety of farms before she and her husband, Ross, purchased a 145-acre sheep’s milk dairy just outside the development. “It’s not a toy farm,” she says. “It’s serious agriculture.” Serenbe Farms is indeed professionally run, by a young idealist named Ashley Rodgers, who makes a comfortable living and has four full-time interns to boot. (They get a monthly stipend and free housing.)

Williams calls Serenbe the “leading edge” of the new suburbs, propelled by a history of what’s been shown to make people happy: physical closeness, which encourages human interaction; proximity to amenities, which creates the sense that what you need is readily at hand; green spaces, cultivated and wild, that provide places to play and explore; and varied architecture, which fosters a feeling of security, because it creates the sense that a place has existed for a long time. “All of these things create a genuine sense of safety,” she says, “which is the most basic element of community and without which happiness is impossible.”

The agritopia takes these principles and cleverly folds in agriculture. Everything new is invariably old. Americans have romanticized farming since the country began. In 1787, Thomas Jefferson wrote to George Washington that “Agriculture... is our wisest pursuit, because it will in the end contribute most to real wealth, good morals & happiness.” Today’s successful sales pitch includes snipping arugula from the garden and then picking apples and strawberries on the stroll home from work. The only thing missing from this fantasy are the bluebirds that take your coat as you walk in the front door.

A few years back, the pioneering architect and urban planner Andrés Duany wrote a manifesto, Garden Cities, proposing that agriculture woven into urbanism represented the future of our cities. “Sustainability to the point of self-sufficiency is where the market is going,” he wrote. But Garden Cities was meant to be more than a market-indicator. It was a warning: “To make a difference in the campaign against climate change,” he wrote, “agrarian urbanism must succeed in being profitable, popular and reproducible—with no downsides if possible.”

Which could be a tough row to hoe.

Ever watch the “Portlandia” sketch in which a couple of earnest diners ask their server not only about the diet of the chicken they are about to consume, but exactly how much land it lived on, and its name? The server returns with pedigree papers to prove that Colin was raised on a woodland diet of sheep’s milk, soy and, yes, local hazelnuts. Ultimately, the diners leave the table to visit the farm and see for themselves how Colin was brought up.

The residents of Bainbridge Island have some of the do-it-ourselves urban progressive preciousness associated with the food scene in Portland, Oregon, some 200 miles south. Within five minutes of entering a downtown coffee shop (where doughnuts are “hand-forged”), I hear enough buzzwords—fair trade, house-made, artisanal, locally sourced—to start a compost heap.

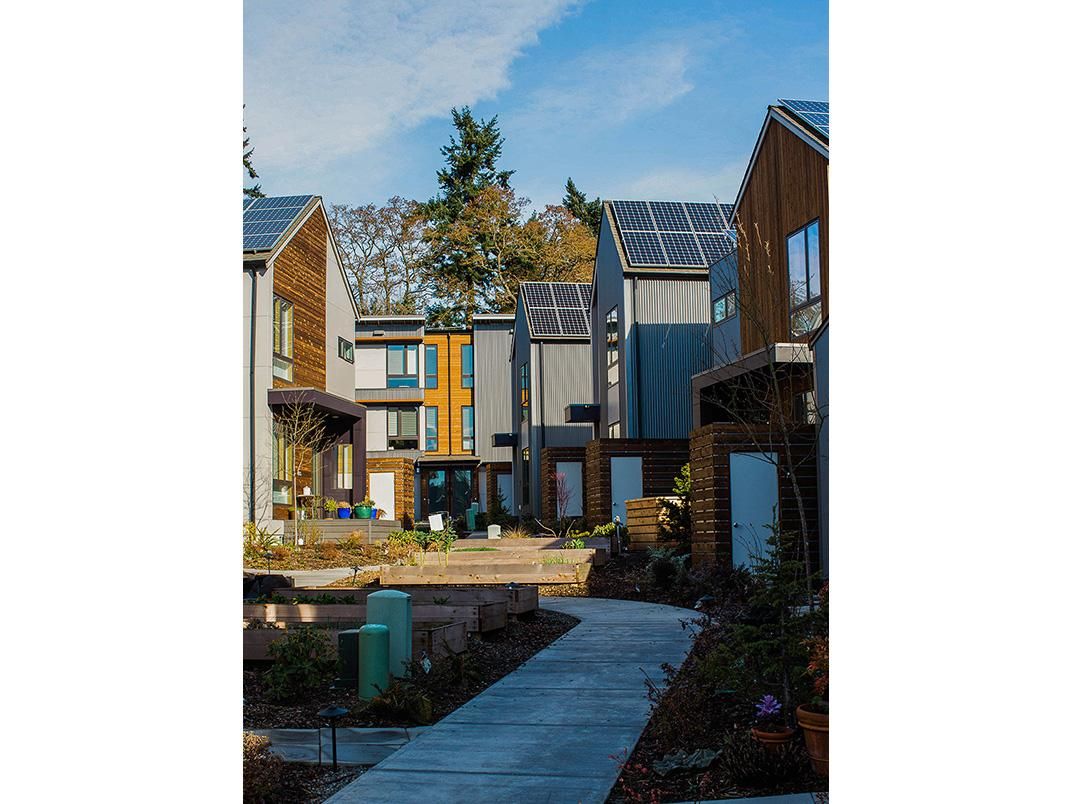

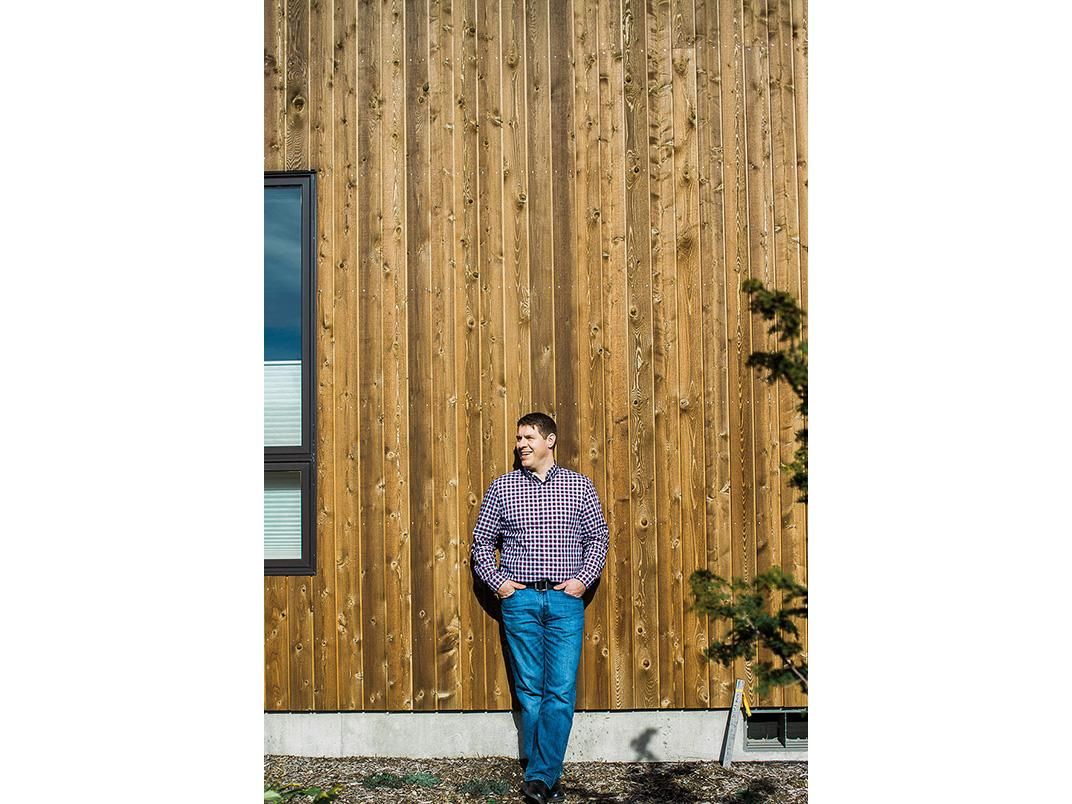

A gossamer-fine rain falls steadily across the Puget Sound, the kind of day Bainbridge Islanders call balmy. Happily, downtown is a five-minute stroll from Grow Community, at eight acres the largest planned solar settlement in Washington state. “The population is 30 percent environmentalists, 30 percent lawyers and 30 percent people who are concerned about the environment and have lawyers,” says project manager Greg Lotakis. “Somehow, that adds up to 100 percent.”

Lotakis escorts me to the Village, Grow Community’s first completed residential neighborhood. Streets are named Seed Path, Root Path and Sprout Path, as befits the setting for an urban farm. Raised pea-patch beds fronting each unit recall World War II victory gardens. Banks of berry bushes line the walkways. The 42 homes and apartments are, for the most part, wedged tightly together, the better to make use of limited space and encourage social interaction. Exteriors are Northwest Modern patchworks of board-and-batten cladding, and panels of concrete and corrugated steel. The cedar siding, I’m assured, comes from sustainably managed forests within 500 miles. There’s so much talk of “leaving small footprints” that I feel like I’m in a colony of elves.

For all its affectations and lack of racial diversity (Lotakis: “There are a lot of white people”), Grow Community is an honest attempt to change the way we live—a contemporary reboot of an old-fashioned American utopia. During the 19th century, when Utopianism had its heyday, the tapestry of sects included Brook Farm’s Transcendentalists, the free lovers of Oneida, New York, and the Shakers, religious cultists so called because they trembled during worship. The Shakers’ biggest problem was that they practiced celibacy, hence they are no longer with us. For them, at least, the road to Utopia was a dead end.

At Grow, Utopian living takes some getting used to. Though berries are there for the taking, some residents are reluctant pluckers. “Folks who weren’t involved with the gardens tend to be harvest-shy,” says resident Ron Kaplan. “Some berries went bad on the vine.” So Kaplan put up signs: “Pick Me.”

Some Village people—resident volunteers—would like to install a public composting machine; others cluck about henhouses that are solar-powered and self-propelled. When chicken coops do come to Grow, don’t be surprised if one of the roosters answers to Colin.

Of all the many things we learned from watching the first season of “The Real Housewives of Orange County,” the most jarring may be the fact that, at the time, seven million American families lived in gated developments.

These modern suburban fortresses are the kinds of places that mostly white and affluent Americans choose to live in when they want to feel safe—from crime, from economic uncertainty, from Americans who are not mostly white and affluent.

Today I’m touring Rancho Mission Viejo, a massive, partially gated community assembled on a swath of amber hills and grasslands where the Real Cattle of Orange County still graze. A brilliant mid-winter sun blooms over the Guest House, a welcome center not unlike the one at Disneyland, a half-hour drive up Interstate 5. The surrounding hillsides are speckled with tens of thousands of fruit trees. Inside, an immense property map hangs over a shelf of plastic lemons and avocados. “Homebuyers can enjoy the exclusive vistas of the citrus groves,” the Guest House greeter tells me, handing me a plastic bottle of water that bears the label: “The Ranch. Drink It In.”

Some might see the nearer roots of developments like Rancho Mission Viejo and other suburban agritopias in the community of Prairie Crossing, the Illinois hamlet founded in 1993 with a 100-acre organic farm and a reconstructed plain at its heart. But the closer prototype might be Columbia, Maryland.

In 1967, the visionary developer James Rouse led several hundred disillusioned city dwellers on a pilgrimage to Columbia. “There will be complete integration of races and economic groups,” he declared. Rouse’s Promised Land, midway between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., was founded on 14,000 acres of cow pasture. He called it the Next America.

Rouse conceived nine villages ringing a shared town center, with clustered housing that encouraged neighborliness, a scheme later picked up by the leaders of the New Urbanism movement. “Columbia is a garden for growing people,” was Rouse’s description. Yet lurking behind Rouse’s egalitarian pronouncements was a shrewd capitalist. When he was not playing the Pied Piper, he was a mortgage banker. He made his fortune assembling other people’s money and charging interest for it, and Columbia’s first wave of utopians were followed by speculators buying homes for 5 percent down and getting equity as fast as possible. As Rouse’s people garden bloomed—Columbians now number about 100,000—housing prices swelled as if dosed with Miracle-Gro.

By the early ’80s, New Urbanism had sprung up to pitch itself against what it saw as the lifeless, land-guzzling sprawl of suburbia. It proposed that beauty—a virtue low on planners’ agendas for much of the last century —mattered as much as function. In model New Urbanist towns like Florida’s Celebration and Seaside (the latter designed by Andrés Duany and his wife, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk), America’s alienating car culture was replaced by a matrix of foot and bike paths; porches returned to the street-facing side of homes; and parks and playgrounds became communal meeting grounds.

Among New Urbanism’s snarkier jeremiads was James Howard Kunstler’s 1993 book The Geography of Nowhere, which savaged the burbs’ “immersive ugliness”—and then it got mean. His catalog of the “brutal” and “spiritually degrading” landscapes of suburbia encompassed “the jive-plastic commuter tract home wastelands, the Potemkin village shopping plazas with their vast parking lagoons, the Lego-block hotel complexes, the ‘gourmet mansardic’ junk-food joints, the Orwellian office ‘parks’ featuring buildings sheathed in the same reflective glass as the sunglasses worn by chain-gang guards, the particle-board garden apartments rising up in every meadow and cornfield, the freeway loops around every big and little city with their clusters of discount merchant marts, the whole destructive, wasteful, toxic, agoraphobia-inducing spectacle that politicians proudly call ‘growth.’”

Asked recently if he had a solution to our problems, Kunstler said, “I don’t like talking about ‘solutions.’ I prefer talking about intelligent responses.”

Under the sprawling California sunshine at Rancho Mission Viejo, the Guest House greeter drives me through the village of Gavilán, an exclusive enclave reserved for residents aged 55 and older—a Tomorrowland for housewives and househusbands with rapidly dwindling tomorrows.

Gavilánters enjoy privacy behind an electronically monitored, double-gated entrance and amenities like a lounge with tapas and a happy hour. “Rancho Mission Viejo cultivates real community and an authentic, fresh new way of living,” the greeter says, as we drive through a bewildering maze of gingerbread casitas and Spanish-style condos.

Eventually, we reach a cul-de-sac with no exit, no parked cars, no people on the sidewalk. In fact, no sidewalks. At the end of the street is a raised plot for growing vegetables, herbs and fruits. It’s enclosed by a daunting iron fence and protected by a security system requiring an access code.

At Gavilán, even the cabbages and cauliflowers live in their own gated development.

While moonlighting as a gentleman farmer, S.J. Perelman made several important discoveries. One was that there are no chiggers in an air-conditioned movie theater. Another, “that a corner delicatessen at dusk is more exciting than any rainbow.”

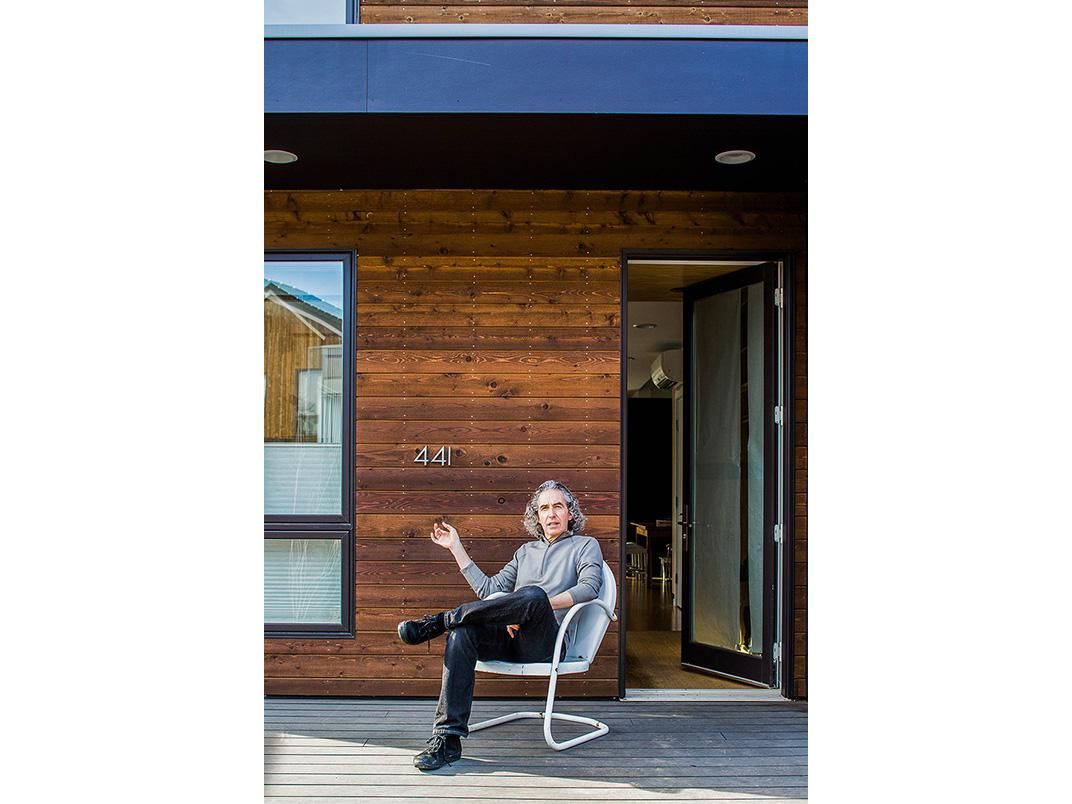

Daron Joffe concedes the first point, but quibbles with the second. The 38-year-old agricultural consultant—or, as he puts it, entre-manure—lives to make a difference in the world one homegrown organic heirloom tomato at a time. Joffe, who goes by the handle Farmer D, is lean and wiry, with skin the color of butter toffee. He has about him a sort of intimation of abundance, as if, like a magician, he might suddenly reach into a pocket and draw forth a goat’s horn overflowing with cherries, violets and spinach.

Under a stingy brim straw hat of indeterminate age, Joffe strolls past a wild meadow of nasturtiums, beets, carrots and celery—a cover crop medley based on the feedback of food banks near the nonprofit farm he runs in Encinitas, a small coastal town north of San Diego. He gathers some flowers and lays them in the crook of his right arm. The sun is shining.

Joffe was born in South Africa and grew up in Atlanta. During his freshman year at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a deli sandwich changed his life. As he was about to bite in, he paused to ponder the ingredients: the turkey, the tomato, the lettuce, the slice of Swiss. He wondered why he knew so little about how that sandwich came to be. “I was inspired to grow a sandwich from scratch,” Joffe says.

He dropped out of school to apprentice at a biodynamic farm. Within a couple years, he used his bar mitzvah money to make a down payment on 175 acres in southwest Wisconsin. Since then he has set up dozens of organic farms and gardens in prisons, schools and resorts; opened a retail urban farm store in Atlanta; put out his own line of sawhorse coffee tables; and written a gardening handbook called Citizen Farmers, which includes a meditative section on “composting for the soul.” (Equal to Joffe’s passion for farming is his passion for Judaism.)

Joffe was also the first farm manager at Serenbe, but he left after two years. “I moved on,” he says. He’s still high on agritopias, if not all of their manifestations. “Agriculture can be a hard concept for developers to wrap their heads around,” he told me. The farm itself is too often “an unintegrated afterthought,” squeezed into a corner of the development, and the hired farmers have little incentive to feel like a part of the community. Joffe says the mentality of agridevelopers tends to be, “Let’s get a random local farmer, tell him he can use the land for free and just let him farm”—essentially feudal serfs working the fields of wealthy landowners.

“The farmer wants to have equity and something to call his own,” says Joffe, who is married with two small kids. “You want to raise your family in these neighborhoods—a lot of which are not affordable. When you plant a fruit tree, you want to know that your grandkids are going to eat off it. In these communities, those things can be real challenges.” According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 91 percent of American farm households—those which devote their livelihoods to the practice and lifestyle on agricultural land far from urban centers—have at least one family member working a non-farm job to make ends meet.

“It’s well known that local specialty crop farming is difficult at best and pretty much not profitable anywhere,” says Quint Redmond. “It’s why there are very few farmers.” Redmond sees himself as a prophet of a true agritopian future. Or, rather, an agriburbian future: He and his wife, Jenny, run Agriburbia®, a Colorado land-planning company. They launched the operation hoping to transform the nation’s burbs by converting 31 million acres of idle lawn to food production. Redmond envisions sowing golf course fairways with kale and corn and edging greens in chives and basil—maximum efficiency, while more or less turning a day on the links into an exercise in salad making.

So far his schemes have been unrealized. After 12 years, he’s developed one three-quarter-acre model garden outside Denver and has proposals in the design phase for thousands of acres of other people’s private farmland—stockpiled by eager agritopians-to-be in anticipation of the coming Agriburbia®.

I thought back to the enlightened souls at Serenbe, full of confidence and communal feeling. Rebecca Williams, the sheep farmer, was sure that the model was reproducible. “All it takes is a handful of people with a shared vision, and a willingness to invest in the kind of development that people are enamored with and willing to pay for,” she said. Custom-built homes in Serenbe can run as high as $3 million. “Who wouldn’t want to live here?” asked Jana Swenson, who’s married to the retired professor E.C. Hall and has lived in a couple of houses in the community. “That is, if you could afford it.”

Money—or lack of it—is no longer the main obstacle to Joffe. Last year the Leichtag Foundation, a Jewish philanthropic nonprofit organization, put him in charge of its new community agricultural center in Encinitas. The foundation had purchased the remaining 68 acres of the once vast Ecke Ranch, the nation’s largest producer of poinsettias, whose other 850 acres had been sold to developers in the 1990s to transform the farmland into neighborhoods and shopping centers.

The new property is smack in the middle of a jumble of tract homes, but Leichtag promised to use it for the common good, not for an uncommon profit. “We’re introducing a farm into an existing suburb in a grassroots way,” says Joffe, who grows produce for the needy as part of the organization’s food pantry outreach and commitment to the concept of tikkun olam, a Hebrew phrase meaning “repair the world.” About a quarter of the county’s population can’t cover the area’s high cost of living.

Last fall, his team laid the groundwork for a five-acre food forest that will be layered with plants like plum, date and pistachio trees and link up to a public trail. Whatever isn’t donated to charity will be free for the taking. “Our farm project is driven by social values,” Joffe says. “It’s not driven by a real estate developer. It’s not about selling houses. It’s about getting people reconnected to food.”

Developers eager to cash in on Joffe’s cachet often approach him about brand partnerships, and when I ask him how he feels about real estate people jumping on the agritopia bandwagon, he tenses his body, as from a blow. “I have some concerns,” he says. “I hear the jargon used and think, ‘This is coming from the wrong place. These people don’t get it. This makes the entire movement look bad.’ By the same token, you hope there are well-considered models out there that people will look to and learn from.”

Perelman, for his part, said his time in the tall rhubarbs had made him a new man. His cheeks “developed the ruddy vitality of a pail of lard,” his fingers were “permanently knotted with arthritis” and his life-insurance beneficiaries discussed him “openly in the past tense.”

Related Reads

Citizen Farmers

Garden Cities: Theory & Practice of Agrarian Urbanism