How General Motors Introduced the Idea of a ‘Concept Car’

Eighty years ago, the Buick Y-job was billed as the car of the future

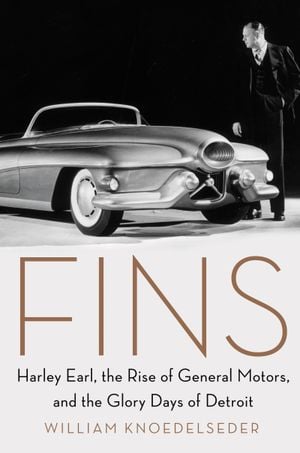

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/58/e0/58e0b165-b0fc-4224-b8b1-613ccbd8a199/harley_earl_and_y-job.jpg)

Harley Earl, the head of design at General Motors, one-upped the entire industry in 1939 when he unveiled a singular car that was not intended for public sale and didn’t even have a proper name. Technically, it was a Buick. Harlow Curtice, head of GM’s Buick division, had provided the chassis and design budget, and Buick’s chief engineer, Charlie Chayne, was part of a small team that worked on it for 18 months in a separate secured studio. They dubbed it the “Y Project” in an ironic nod to the experimental “X Projects” that proliferated in the automobile and aircraft industries, but Harley kept referring to it as the “Y-job,” and the name eventually stuck. It was to be his personal car, after all.

“I just want a little semi-sports car, a kind of convertible,” he told the team at the outset, though he soon decided the Y-job would be a “boattail,” a body style defined by a rear deck that tapered to a prow point and long popular among wealthy custom car aficionados. Edsel Ford and Packard design chief Ed Macauley drove boattail roadsters created by their styling staffs; Errol Flynn and Marlene Dietrich tooled around Hollywood in limited-production Auburn Speedsters, the most flamboyant of the boattail breed.

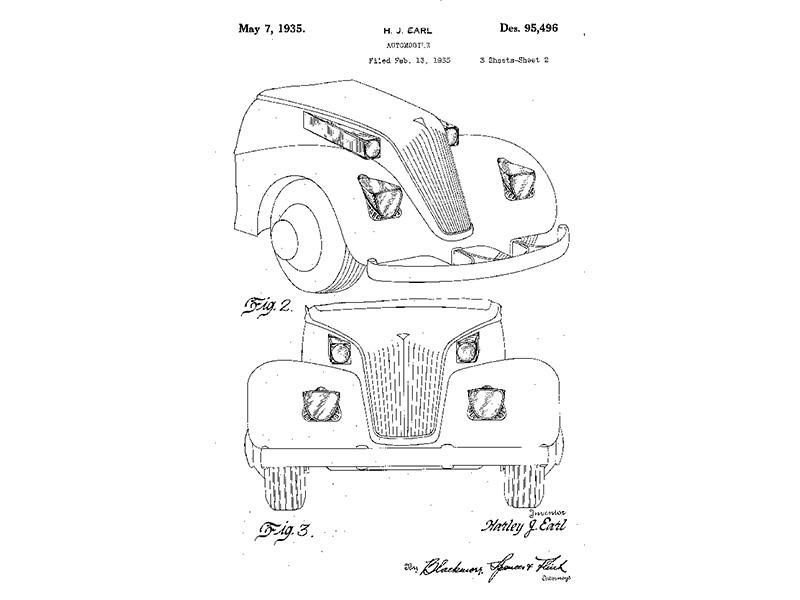

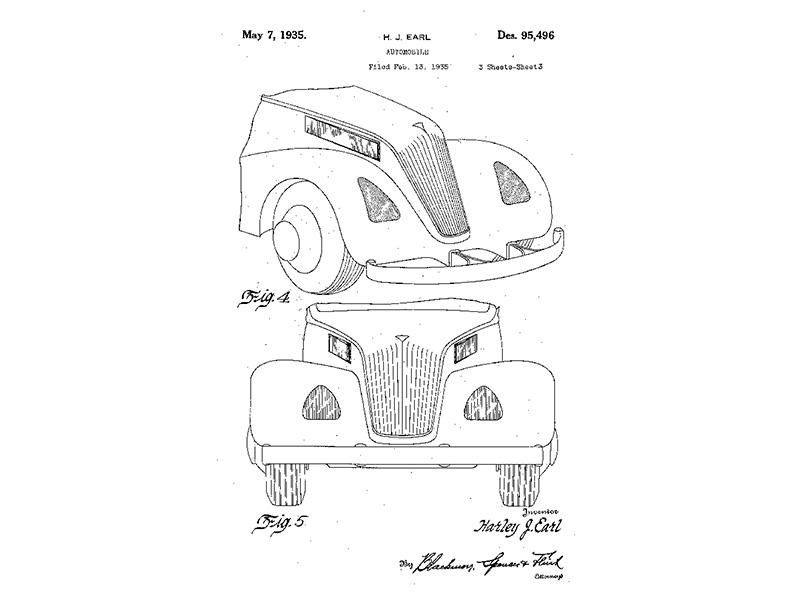

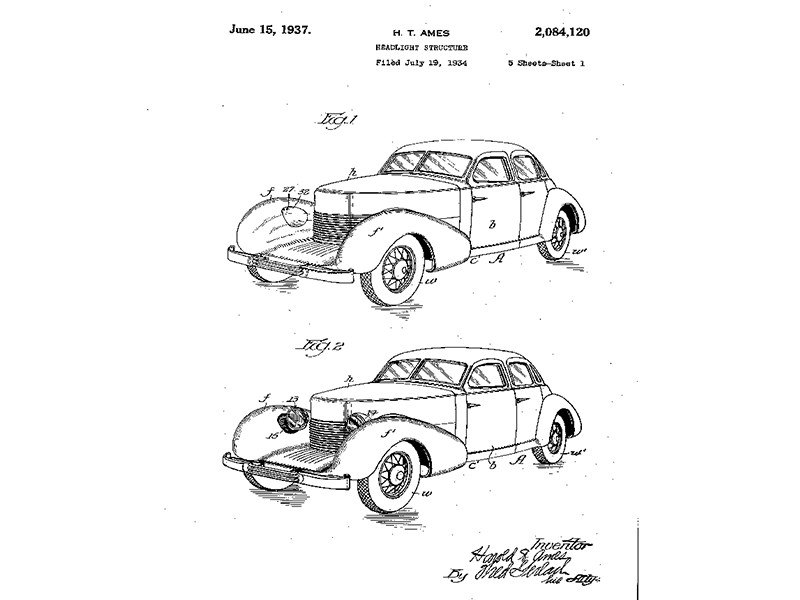

The Speedster was Harley’s kind of car—low-slung, with a long, narrow hood that radiated power, four chrome exhaust pipes snaking out of the engine compartment into the front fenders, and a raked V-type windshield that made it appear to be speeding even when standing still. Designed by Gordon Buehrig, it was a car that demanded to be noticed. But it was also a car of the past, with a vertical grille and headlights mounted on stanchions—beautifully designed, classic, and outdated. The Indiana-based Duesenberg-Auburn-Cord Company sold fewer than 200 Speedsters between 1935 and 1937, when it went out of business.

Harley wanted the Y-job to be a car of the future. Toward that end, he pushed the team relentlessly to come up with styling and mechanical features that hadn’t been seen or even imagined before, a process so arduous and frustrating at times that they began calling it the “Why job.” But the result was a masterpiece of innovation.

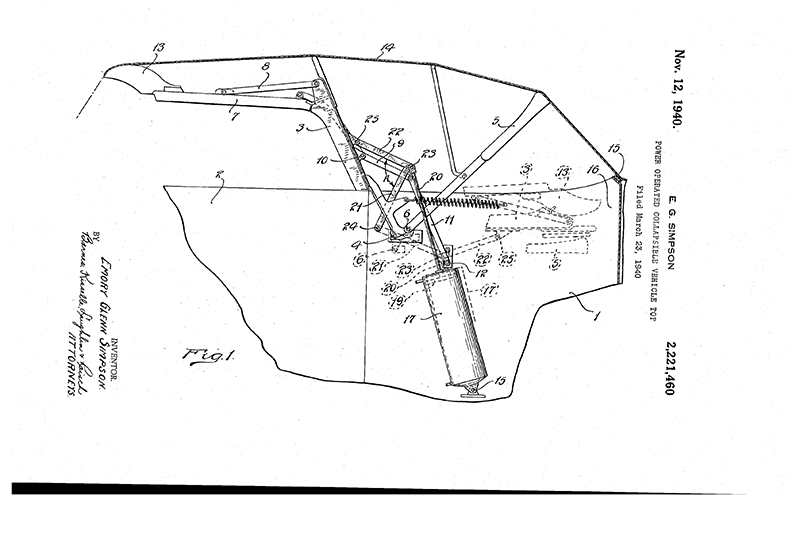

Completed in late 1938 at a cost of about $50,000 (20 times the purchase price of a Speedster), the Y-job boasted a long list of firsts that included a power-operated soft top that stowed beneath a hinged rear-deck panel, power windows, push-button outer door handles, retractable headlights that opened and closed like human eyelids at the turn of a dashboard switch, and front fenders that flowed back through the doors. Between its broad horizontal grille and tapered tail, the car stretched more than 17 feet yet stood only 58 inches high at the top of the windshield (the same as the Speedster). Harley looked like a giant standing next to it. That he could climb in and out with ease was a testament to the underlying engineering. The glossy black finish seemed at odds with his love of bright colors, but it lent a look of sophistication that other sports cars lacked. The Y-job was an exquisitely tailored tuxedo to the Speedster’s flashy Hawaiian shirt.

At some point in the design process, Harley discussed with GM executive Alfred Sloan and Harlow Curtice the idea of giving the Y-job a broader purpose, of using it as the basis of an ongoing program to test styling concepts with consumers far in advance of production. Most car buyers didn’t know exactly what they wanted until they saw it sitting in front of them; that’s why millions of them packed the auto shows every year. But if the Y-job and other GM “cars of the future” toured the show circuit, Harley reasoned, then attendees could see what might be available several years down the road and the company could log their reactions before it spent tens of millions of dollars retooling factories to build a car, or thousands of cars, the public might reject.

Harley’s plan was for the Y-job to make its official debut during the 1939 New York Auto Show at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The event coincided with a GM publicity push to introduce the work of the Styling Section to the automotive press. As part of that PR campaign, the company published a remarkable 32-page booklet, Modes and Motors, illustrated in the art deco style, which traced the evolution of art through human history—from the first cave painting in Spain to the Egyptians, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Greeks and the Romans, Chinese and Moors, from the Dark Ages to the Italian Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution. The introductory passage reads like something Steve Jobs might have written more than half a century later: “Art in industry is entirely new. Only in recent years has the interest of manufacturer and user alike been expanded from the mere question of ‘does it work?’ to include ‘how should it look?’ and ‘why should it look that way?’ Appearance and style have assumed equal importance with utility, price and operation.”

Harley didn’t write the text, but his personal experience at General Motors clearly drove the booklet’s allegorical narrative, which told of the “artist” who once regarded manufacturers with “thinly-concealed contempt” and thought of them as “rough coarse men whose sole purpose in life was to make money” and who did not “feel the need to have an artist tell them how to design their products.”

According to the narrative, “The job of the designer [is] to bring together the science of the engineer and the skill of the artist,” noting that finally “the artist and the engineer have joined hands to the end that articles of everyday use may be beautiful as well as useful. Probably in no field have the results of the application of art to the products of industry been more apparent than that of the automobile.”

As for the future, Modes and Motors concluded, “Certain it is that out of the merger of art, science and industry have come new techniques that have within themselves the ability to create an entirely new pattern and setting for the life of the world.”

The Y-job was exhibited at the New York Auto Show, but its debut turned out to be its swan song as well. After the show, Harley shipped the car to his home in Grosse Pointe and began driving it to and from work every day. It was the ultimate vanity vehicle, outclassing anything in Edsel Ford’s garage and never failing to draw admiring stares as Harley cruised along Lake Shore Drive, usually with the top down.

“His head would stick up above the windshield and he had to duck when he put the top up,” said Clare MacKichan, a designer in GM’s Chevrolet division. “We’d often see him come in on a morning with a light sprinkle of rain, but the top would be down.”

Despite that drawback, Harley loved the car and drove it for years.

Excerpted from Fins by William Knoedelseder. Copyright 2018 by William Knoedelseder. Published with permission from Harper Business and HarperCollins Publishers.