How the Invention of Scotch Tape Led to a Revolution in How Companies Managed Employees

College dropout Richard Drew became an icon of 20th century innovation, inventing cellophane tape, masking tape and more

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/01/5301d9bb-59fc-432c-8b8c-5785ef31a05a/scotch_tape_dispenser.jpg)

Richard Drew never wanted an office job. Yet the banjo-playing college dropout, born 120 years ago this Saturday, would go on to spend some four decades working at one of America’s largest multinationals, and would invent one of the best-selling and most iconic household products in history.

That product is Scotch transparent tape, the tape that looks matte on the roll but turns invisible when you smooth it with your finger. Every year its manufacturer, 3M, sells enough of it to circle Earth 165 times.

Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota on June 22, 1899, Drew spent his youth playing banjo in dance halls, eventually earning enough money to attend the University of Minnesota. But he only lasted 18 months in the engineering program. He took a correspondence course in machine design, and was soon hired as a lab tech by the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company, which was then in the business of manufacturing sandpaper.

Transparent tape was not Drew’s first ingenious invention. That was another household must-have: masking tape.

In Drew’s early days at the company he would deliver sandpaper samples to auto manufacturers, who used it for the painting process. In the 1920s, two-tone cars were trendy. Workers needed to mask off part of the car while they painted the other, and often used glued-on newspaper or butcher paper for the job. But that was difficult to get off, and often resulted in a sticky mess. Drew walked into an auto body shop one day and heard the "choicest profanity I'd ever known" coming from frustrated workers. So he promised a better solution.

He spent the next two years developing a tape that was sticky yet easy to remove. He experimented with everything from vegetable oil to natural tree gums. A company executive, William McKnight, told Drew to stop messing around and get back to his regular job, which he did, but Drew kept doing tape experiments on his own time.

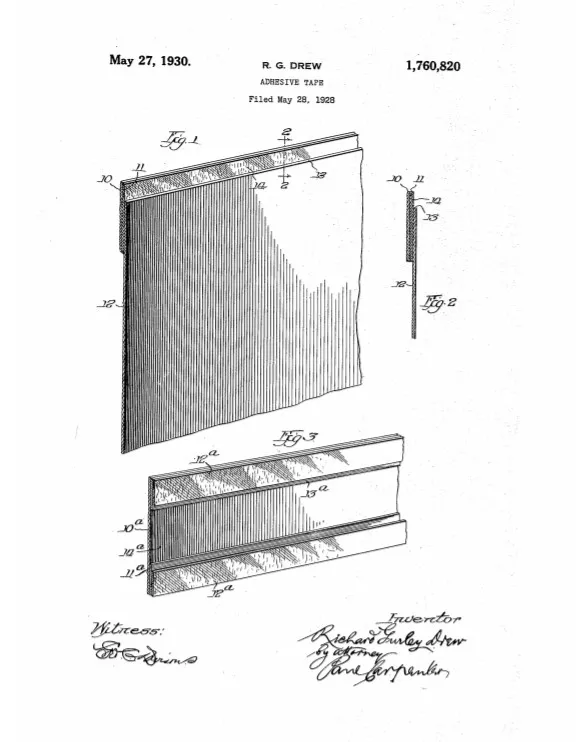

Eventually, in 1925, he found a winning formula: crepe paper backed with cabinetmaker’s glue mixed with glycerin. But his first version of masking tape only had adhesive on the edges. When the painters used it, it fell off. They allegedly told Drew to take his “Scotch” tape back to the drawing board, using the term to mean “cheap,” a derogatory dig at stereotypical Scottish thriftiness. The name, so to speak, stuck. It would be used for the larger range of tapes from 3M (as the company would later be known). Drew received a patent for his masking tape in 1930.

That same year, Drew came out with his waterproof transparent tape after months of work. The tape took advantage of newly invented cellophane, but the material wasn’t easy to work with, often splitting or tearing in the machine. The adhesive was amber-colored, which ruined the cellophane’s transparency. Drew and his team went on to invent adhesive-coating machines and a new, colorless adhesive.

The tape was released just as America plunged into the Great Depression, a time when “mend and make do” became a motto for many. People used Scotch tape for everything from mending ripped clothing to capping milk bottles to fixing the shells of broken chicken eggs. At a time when many companies were going under, tape sales helped 3M grow into the multibillion-dollar business it is today.

William McKnight, the executive who told Drew to stop working on Scotch tape, eventually became chairman of 3M’s board. Through Drew, McKnight came to understand that letting researchers experiment freely could lead to innovation. He developed a policy known as the 15 percent rule, which allows engineers to spend 15 percent of their work hours on passion projects.

“Encourage experimental doodling,” McKnight said. “If you put fences around people, you get sheep. Give people the room they need.”

The 15 percent rule has deeply influenced Silicon Valley culture—Google and Hewlett Packard are among the companies that give their employees free time to experiment. The Scotch tape story is now a classic business school lesson, a parable of the value of instinct and serendipity, which Drew once called, "the gift of finding something valuable in something not even sought out."

After his tape successes, Drew was tapped to lead a Products Fabrication Laboratory for 3M, where he was given free rein to develop new ideas. He and his team would file 30 patents, for inventions from face masks to reflective sheeting for road signs. He would also become known as a great mentor, someone who helped young engineers hone their instincts and develop their ideas.

Drew retired from 3M in 1962 and died in 1980, at the age of 81. In 2007, he was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

“Richard Drew embodied the essential spirit of the inventor, a person of vision and unrelenting persistence who refused to give in to adversity,” said 3M executive Larry Wendling at Drew’s induction.

Today, a plaque at the 3M Company in Drew’s hometown of Saint Paul commemorates his most famous invention. It reads, in part: “Introduced during the Great Depression, Scotch Transparent Tape quickly filled the need of Americans to prolong the life of items they could not afford to replace.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)