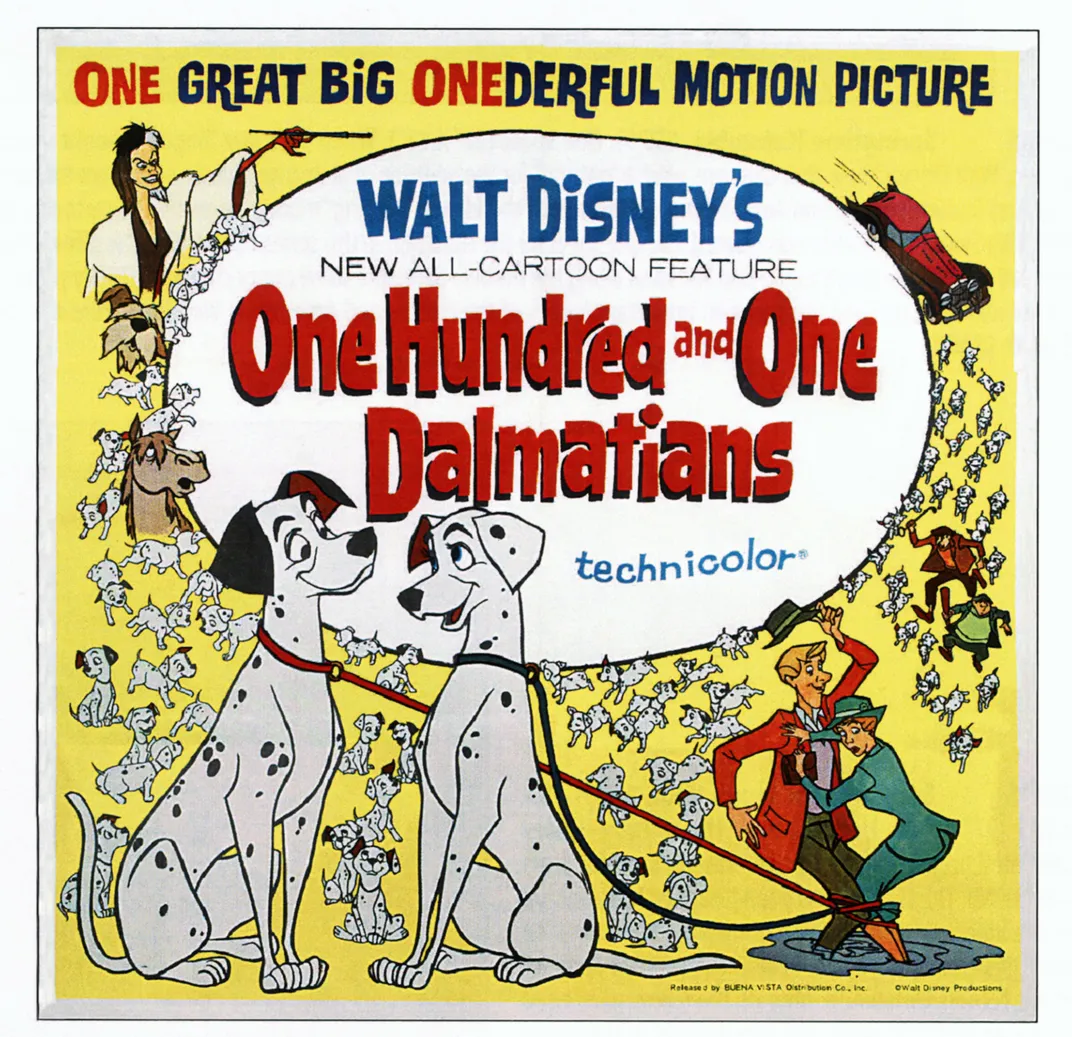

How ‘One Hundred and One Dalmatians’ Saved Disney

Sixty years ago, the company modernized animation when it used Xerox technology on the classic film

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/3b/bf3b45bc-d207-4436-9045-b9d57ee3cf21/gettyimages-1137259243.jpg)

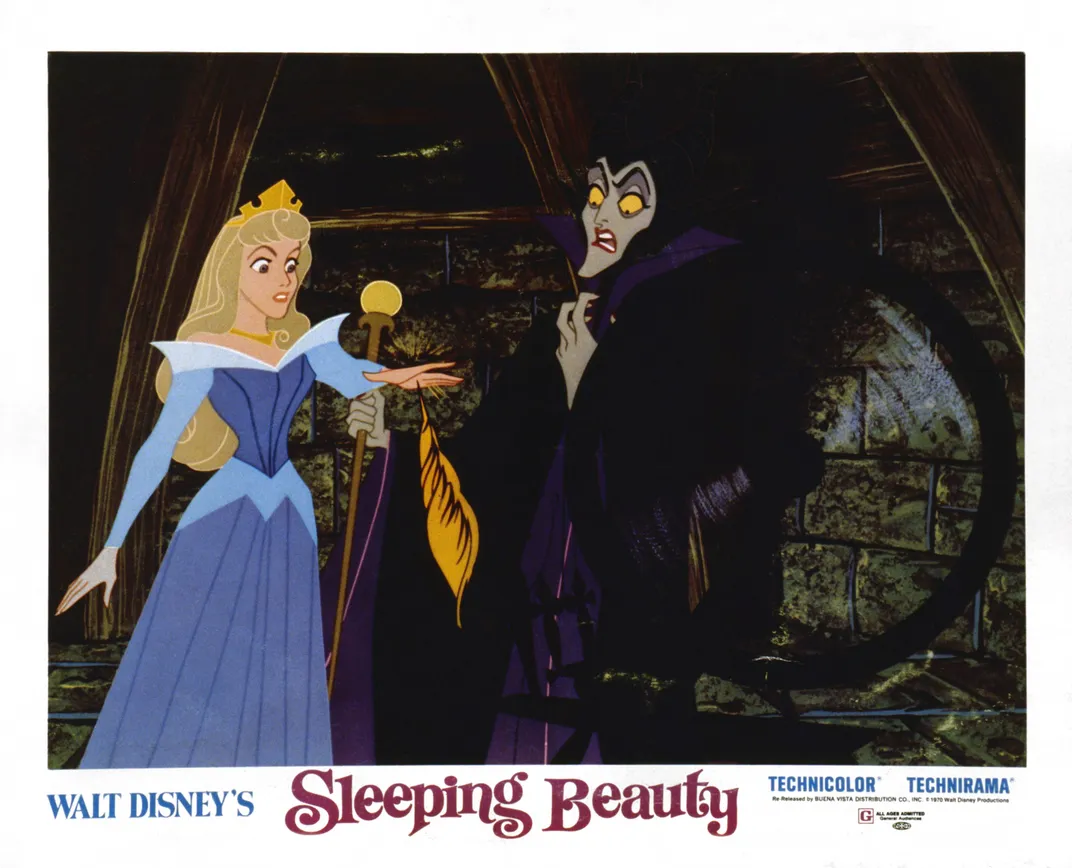

Take a closer look at Walt Disney’s 1961 animated One Hundred and One Dalmatians film, and you may notice its animation style looks a little different from its predecessors. With its dark outlines defining characters from backgrounds, its departure from the subtle and sensitive animation of Sleeping Beauty just two years prior was considered jarring to some.

That’s because the film is completely Xeroxed. The technology, invented by American physicist Chester Carlson in the 1940s, completely streamlined the animation process, and ultimately saved Disney’s beloved animation department.

“The lines were often very loose because they were the animators’ drawings, not assistant clean-up drawings. It really was a brand new look,” says Andreas Deja, former Walt Disney animator and Disney Legend, about Xerox animation. Deja is well known for his work in Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992) and The Lion King (1994), and more recently, Enchanted (2007) and The Princess and the Frog (2009).

With animation growing more expensive, tedious and time-consuming in the mid-20th century, Xeroxing allowed animators to copy drawings on transparent celluloid (cel) sheets using a Xerox camera, rather than having artists and assistants hand-trace them.

Prior to this experiment with Dalmatians, based off of Dodie Smith’s 1956 novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians, artists first drew concept art to create a character. They sketched characters on animation paper, or cheap newsprint, and then assistants cleaned up the sketches, making sure they were uniform. Consistency was key for characters, as assistants had to follow every detail of a sketch, down to the buttons on a jacket. Once the drawings were ready, they moved to the inkers, who traced the sketches on the front side of shiny, cel sheets. After drying, the cel was then turned over for painters to paint the characters within those lines, to get them as opaque as possible. The line work grew even more complicated; different colors, weights and thicknesses were vital for giving animated characters the realistic qualities viewers expected. The colors of the paint also demanded extreme attention. Disney mixed its own paint, making their animations unlike any other. In fact, women in the ink and paint departments took rouge from their compacts and applied it to Snow White’s cheeks to give her natural look in the 1937 film.

Disney movies tend to have 12 to 24 images, or cels, per second, meaning that thousands of cels, if not more, go into a single animated film. Sleeping Beauty, for instance, required nearly one million drawings.

In fact, it was Sleeping Beauty that set the stage for the new Xerox technique. Considered a classic now, the film didn’t perform nearly as well as expected in the box office. The incredibly detailed work of art took $6 million to make, and it only made a little over $5 million, resulting in a loss of nearly one million dollars.

In its aftermath, Disney discussed shrinking the budgets for future projects and even closing down the animation studio. But, in a money-saving effort, Ken Anderson, art director for Dalmatians, the next film in the works, suggested using Xerox. The technique had been tested on a few animated shorts. Goliath II was one of these trial runs, says Deja. The 1960 animated short was written by Bill Peet, who also single-handedly storyboarded Dalmatians, setting the scenery and the continuity of the film’s camera shots.

While some inkers still made small corrections to the animators’ sketches before they were Xeroxed, these jobs were mostly replaced by Xerox machines, mechanizing the tracing process. The polished sketches went straight to a Xerox machine, which copied them onto cels. Then, these cels went to the paint department, where artists flipped them over and painted the characters.

The difference in visual effect between the original method of animation used by Disney from the 1930s to ‘60s and Xerox animation laid in the lines. The powder, or toner, never clung perfectly, and sometimes flaked off of the lines a bit, due to the slickness of the cel. In Xerox animation, characters and backgrounds were outlined in one color: black, brown or gray. The character Roger Radcliffe in Dalmatians was entirely outlined in black. These dark lines often come off as harsh, whereas animators in the original style could outline characters with multiple colors, giving the drawings a gentler, more gradient look. Aurora from Sleeping Beauty had yellow outlines to match her hair and blue outlines to match her dress.

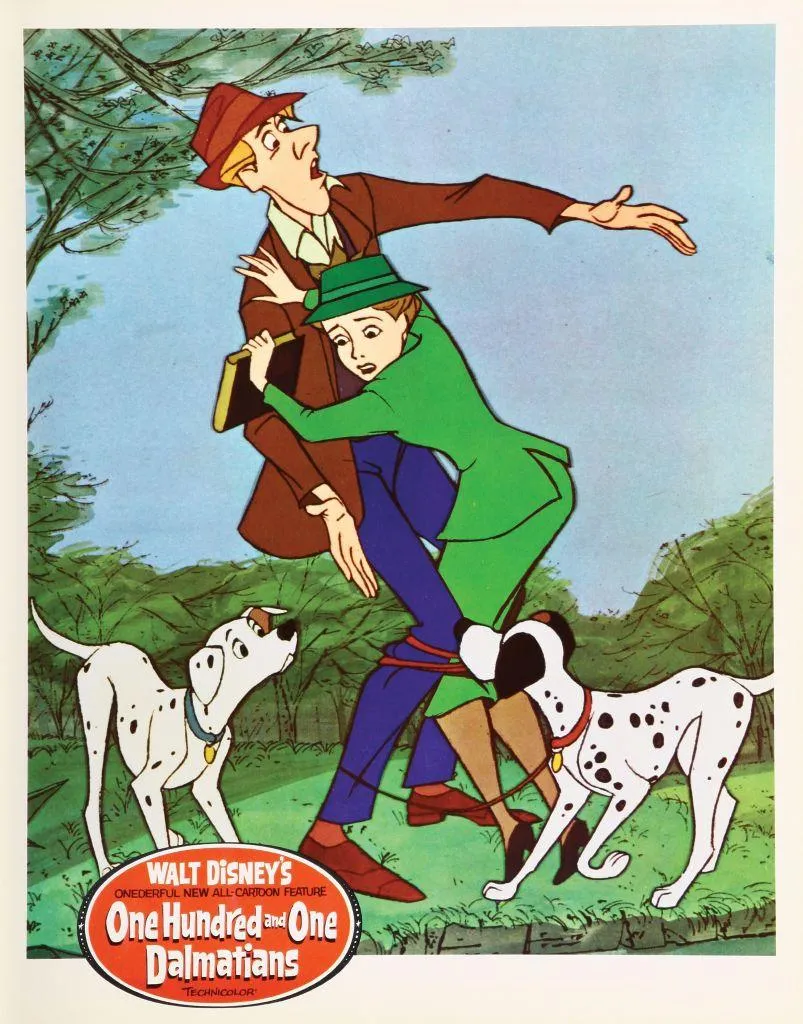

“The lines have this kind of friable quality to them; they're a little bit crumbly, and uneven,” says Charles Solomon, Disney animation critic and historian. “If you look at a still from Dalmatians, you'll see the line isn't that perfect, elegant, calligraphic stroke that you saw in the older films.”

While Walt Disney didn’t necessary dislike Xeroxing, he found it hard to get used to the harsh look, especially for a story like Dalmatians that he adored. “It took a few more films before he softened his attitude toward it,” says Deja. He was also more concerned with upholding Disney’s iconic quality and charm than with finances. “Walt never worried about money. To him, it was just something you could spend to do things you wanted to,” says Solomon.

Animators, on the other hand, praised the new technique. This was the first time their sketches weren’t altered through the tracing and copying process. “[Animators] felt like with each tracing step, the drawings lose life,” says Deja. “And all of a sudden, their drawings were kept.”

Dalmatians was actually well suited for Xeroxing. Think about how tedious animating all 101 spotted dogs would have been by hand. “An animator could do groups of two or three or four puppies, and then by staggering their motion, you could expand that to however many puppies you needed in that scene,” says Solomon. “Retracing all those puppies by hand would have been just horrendous amounts of work.”

The sharp, angular features of Cruella de Vil, the infamous antagonist of Dalmatians, were accentuated by the dark outlines from Xeroxing. “When you see Cruella, she's very sketchy. Her lines boil all over the place, but somehow it works because it was controlled. It wasn't just boiling for boiling sake,” says Deja. Inspired by Cubism, animators stylistically adapted to the flattened graphics of Xerox. Animators weren’t able to move De Vil through space the same was as past characters, like Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty, and had to find a style of movement that fit the design of this character.

Disney used Xerox animation for the next 30 years, making The Sword in the Stone (1963), The Jungle Book (1967), The Aristocats (1970) and lastly The Little Mermaid (1989), which was Xeroxed with brown lines to give the animation a softer touch. The next film, Beauty and the Beast (1991), used a computer animation production system, or CAPS, replacing the Xerox method. This digital ink and paint system allowed artists to scan sketches into a computer and easily color in enclosed areas and touch up the overall drawing. This not only saved more money for the animation department but expanded digital tools for animators, making the film-creating process that much more flexible. While the style was eventually phased out early in the 21st century for computer-generated imagery (CGI), many Disney films, such as Hercules (1997) and Mulan (1998), were products of CAPS.

To remaster early Disney films for DVDs, artists have to go into every frame and repaint the lines on the cels. These touch-ups have been done to varying degrees of success. According to Deja, some films, like The Aristocats, have been over-restored, meaning teams stripped too much grain from the original frames. “Once you take the film grain out, the colors become too bold,” he says. “Sometimes the lines become too thick; it looks like the film was animated with Sharpies, rather than with a thin pencil.” When watching Dalmatians on Blu-ray Disk compared to its original version, the colors are noticeably cleaner and brighter. While these touch-ups are meant to visually improve the film, it might leave fans—who are, no doubt, eager to see the new live-action Cruella starring Emma Stone—nostalgic for the original and its classic, simple appearance.

“The Xerox process allowed for a different look, a more modern look, ” says Deja, “with spontaneous sketches that the animators liked.”