More patients than ventilators. Understaffed hospitals. A snowballing pandemic. Seven decades before COVID-19, a similar crisis strained the city of Copenhagen. In August 1952, the Blegdam Hospital was unprepared and overwhelmed. A 12-year-old victim, Vivi Ebert, lay paralyzed before anesthesiologist Bjørn Ibsen, “gasping for air” and “drowning in her own secretions.” Seven years after liberation from Nazi occupation, a new shadow darkened the streets: the poliovirus. With his hands, a rubber bag, and a curved metal tube, Ibsen reset the boundary between life and death and taught the world how to breathe.

“We were very afraid,” remembers Ibsen’s daughter Birgitte Willumsen of the 1952 outbreak, “everyone actually knew somebody” affected by polio. Waves of young people with fever, headache, upset stomach and stiff neck heralded the arrival of the “summer plague” in cities throughout the United States and Europe. Masquerading as a common stomach virus, the infection established itself in the gut before spreading to the brain and spinal cord. The clinical picture ranged from a self-limited stomach bug to paralysis, shock and asphyxia. Some recovered, but lasting disability, or death, was typical. At the time, the best way to treat respiratory complications of polio was with the "iron lung," a tank that encased polio victims but allowed them to breathe with the help of a vacuum pump. Researchers understood that the virus was contagious, but they could not yet agree on its manner of spreading. Recalls Willumsen, “We really learned to wash our hands.” Nonetheless, the modern sanitation, water supply, housing and medical infrastructure of Western cities offered little protection. A vaccine was not yet available.

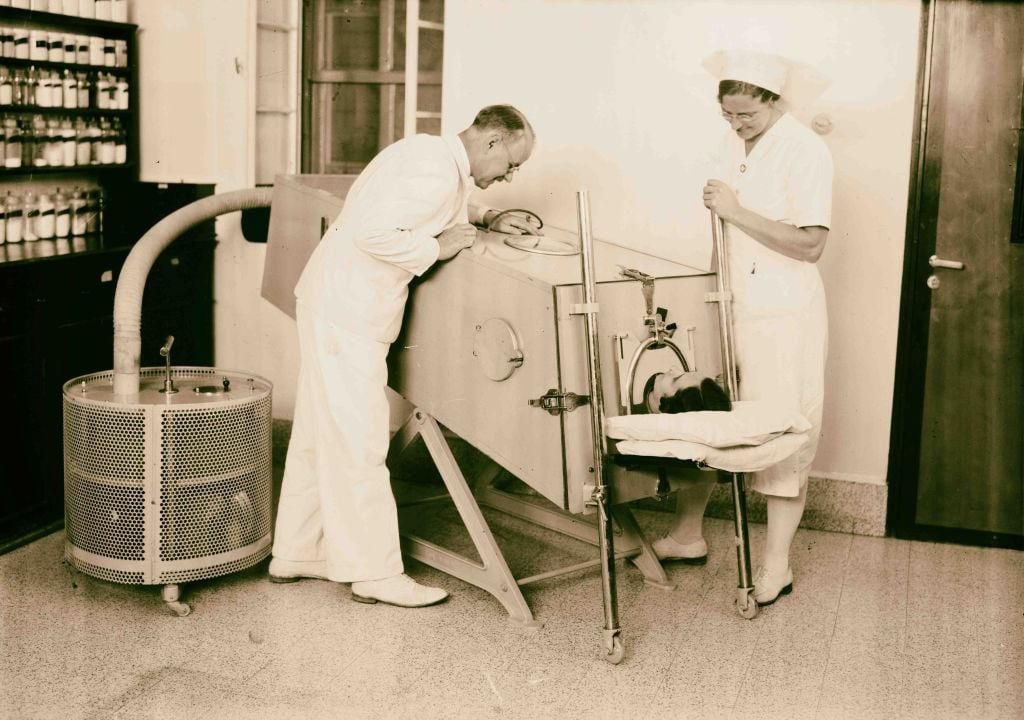

Blegdamshospitalet was the designated “fever hospital” for treating infectious diseases among the 1.2 million citizens of Copenhagen. During the summer of 1952, the staff treated more children with severe polio than they had in the previous decade. At the peak of the epidemic, up to 50 new patients limped, wheeled and wheezed onto the wards each day. With higher attack rates than preceding outbreaks in the U.S. and Sweden, the Copenhagen epidemic was the worst polio crisis that Europe—and perhaps the world—had ever seen. “During these months we have in fact been in a state of war,” wrote Henry Cai Alexander Lassen, Blegdam’s chief physician. “We were not nearly adequately equipped to meet an emergency of such vast proportions.” Hundreds of patients with bulbar polio. One state-of-the-art iron lung ventilator, and a few older, mostly impotent, devices. Concluded Lassen: “Thus the prognosis of poliomyelitis with respiratory insufficiency was rather gloomy at the outbreak of the present epidemic in Copenhagen.”

The prognosis was especially gloomy for young Vivi Ebert, who was dying in front of Ibsen and his colleagues on August 27, 1952, at the height of the epidemic. Vivi suffered from the bulbar variant of polio infection; in addition to causing paralysis, the virus disrupted brainstem control centers for swallowing, breathing, heart rate and blood pressure. At the time, about 80 percent of bulbar polio patients died comatose in the iron lung.

Physicians had long implicated overwhelming brain damage as the cause of bulbar polio deaths. A methodical problem-solver who logged even his music consumption (on November 24, 1997, for example, he listened to Arthur Rubenstein’s rendition of “Fantaisie in F Minor” by Chopin), Ibsen doubted the prevailing theory; he suspected that paralyzed chest muscles compromised respiration. The lungs themselves could sustain life if stronger mechanical muscles could be found. A world war and a chance encounter would lead him to the solution—and to an ethical dilemma that spurred accusations of murder.

A World War, a Rubber Bag and the Ventilator Surge of 1952

Ibsen had been thinking about breathing for years. After completing medical school in 1940, he trained in Denmark's remote northern peninsula, where, according to his son Thomas, the healthcare system consisted of three persons: the doctor, the pharmacist and the priest. Ibsen delivered babies, assisted with surgery, spent long hours with the sick and raised his young children. Isolated by geography and Nazi occupation, opportunities for advanced medical training remained scant, even after the war’s end. Ibsen and his peers looked abroad to the United States and United Kingdom.

Ibsen’s bagging, known as “positive pressure ventilation,” was not widely used at the time, as it contradicted human physiology. Normally, air is instead drawn into the lungs by negative pressure—the vacuum created by diaphragm and chest muscle contraction. Outside of the operating room, negative pressure ventilators, such as Blegdam’s “iron lung,” were the sole means of artificial respiration.

Originally intended to treat victims of industrial accidents, the modern iron lung was developed at Harvard in 1928 by Philip Drinker and Louis Agassiz Shaw. Its nickname derived from the airtight cylindrical tank that enclosed the patient’s body. The head and neck protruded through a snug rubber collar. Electric pumps cycled air in and out of the tank to mimic normal breathing. John Emerson—high school dropout, self-taught inventor and distant relative of Ralph Waldo—fashioned a rival model in 1931 that was cheaper, quieter and more adaptable. However, even Emerson tank ventilators remained prohibitively expensive for most hospitals and served as little more than a costly and claustrophobic deathbed for eight out of ten patients with bulbar polio. A better treatment was needed.

In February 1949, Ibsen relocated his growing family to Boston so he could train in anesthesiology at the Massachusetts General Hospital, the institution credited with the first surgical administration of ether. In Boston, Ibsen fused ruffle-shirted Harvard medicine with Danish pragmatism. Accustomed to the privations of postwar Europe, the young Danes earned a reputation for medical creativity. This spirit would leave a lasting mark on medicine, as young Danes like Ibsen followed other pioneers to the United States and Great Britain to study.

In Boston, Ibsen learned the art of “bagging”—the use of a hand-squeezed rubber bag to breathe for anesthetized patients during surgery; the practice was foreign to Danish physicians at the time. He also learned to bag ventilate patients with tracheostomy tubes—breathing conduits placed in the windpipe through an incision in the neck. Although seemingly rudimentary, this technique became a crucial element of Ibsen’s answer to the bulbar polio crisis of 1952.

The breakthrough came in 1949 at the Los Angeles County Hospital, but few realized it at the time. For centuries, healers attempted positive pressure ventilation, using mouth-to-mouth resuscitation or even a fireplace bellows to treat victims of drowning, opioid overdose and other misfortunes. Physician Albert Bower and engineer Vivian Ray Bennett, supplemented the Emerson-style tank ventilator with an invention that simultaneously inflated the lungs through a tracheostomy. Their new positive pressure ventilator, modeled on an oxygen-supply system for World War II pilots, increased airflow to the lungs. The device decreased the mortality of severe polio from 79 to 17 percent. In 1950, the Bower-Bennett team published their results in an obscure medical journal. The article passed unnoticed by many, but Ibsen, who had returned to Denmark in February 1950 after completing his one-year fellowship in Boston, read it and immediately understood its significance. A reprint of Bower and Bennett’s report in hand, Ibsen met with Lassen, Mogens Bjørneboe (a physician who worked with Lassen at Copenhagen’s fever hospital) and other senior physicians on August 25, 1952, as the bodies of Denmark’s children were stacking high at Blegdam. Positive pressure ventilation, Ibsen argued, was the key to Bower and Bennett’s success, and spare parts from the operating room could deliver Blegdam from catastrophe.

The following day, young Vivi Ebert arrived at Blegdam Hospital with headache, fever and a stiff neck. By morning, bulbar polio was manifest and death inevitable. Lassen agreed to let Ibsen proceed. At 11:15 a.m., at Ibsen’s direction, a surgeon placed a tracheostomy tube in her windpipe, but she deteriorated further. Oxygen levels fell.

Ibsen attached, to Vivi’s tracheostomy tube, a rubber bag filled with an oxygen supply. Air filled her lungs with each squeeze of the bag, but, agitated and drowning in mucus, she bucked and fought the breaths of the junior anesthesiologist. In desperation, to settle her, he administered a large dose of sodium thiopental. The assembled onlookers lost interest and left the room, figuring that the demonstration was culminating in a semi-intentional and lethal barbiturate overdose. However, as the sedative took hold, Vivi’s gasping ceased. Her struggling muscles relaxed, allowing Ibsen to breathe on her behalf. Her lungs cleared, and her condition stabilized. When the thiopental wore off, the team stopped bagging, but she again gasped and floundered. Primitive sensors, repurposed from U.S. Army Air Force and anesthesia applications, signaled falling blood oxygen and rising carbon dioxide. Ibsen and colleagues re-administered the sedative and resumed bag-ventilation, and, as before, she improved.

Vivi would live if they could keep squeezing the bag.

Standing on the shoulders of Bower, Bennett and unsung fireplace bellows-squeezers, Ibsen improvised the first practical treatment for bulbar polio. His breakthrough shepherded Vivi Ebert and the city of Copenhagen through the grimmest days of the outbreak, and cemented his reputation as a founding father of intensive care medicine. But later that afternoon, Ibsen and Lassen needed to find extra hands.

***

Over the next eight days, the leadership of Blegdam Hospital organized bag ventilation for every patient with respiratory failure. The effort consumed 250 ten-liter breathing gas cylinders each day. It was an unprecedented logistical challenge; up to 70 patients required simultaneous, around-the-clock ventilation at the height of the epidemic. “In this manner we avoided being placed in the dreadful situation of having to choose,” wrote Lassen. They recruited approximately 1,500 medical and dental students to assist. “It was simply necessary and there were not enough physicians with these skills,” remembered Ibsen. As young as 18 years old, the volunteers were but able-bodied reflections of the peers they were ventilating. Perhaps nothing but chance separated patient from practitioner. Amazingly, not a single bag-squeezer would catch polio while on duty at Blegdam.

The students’ assignment began with a few hours of instruction, and they were soon sent to the wards. They bagged in shifts, pausing for meals and cigarettes. The young students read to their patients and played games. They learned to read their lips. And they were heartbroken when their patients died. Uffe Kirk was 25 years old when he helped to organize the medical student response in 1952. In a letter to a colleague, he recalled: “At worst, the patients died during the night. The light in the wards was dimmed in order not to disturb the patients in their sleep. But the faint light and the fact that the students were not able to tell anything from the ventilation made it impossible for the students to know that their patient had died. It was therefore a shock for the student when morning came and he/she realized that the patient had been dead for a while.”

Few medical innovations would be so immediate and definitive. In one week, the mortality of bulbar polio fell from 87 to barely 50 percent. By November, the death rate dropped again to 36 percent. As the embers of the Copenhagen outbreak cooled in March 1953, only 11 percent of patients who developed bulbar polio died.

Healers from different specialties buttressed the mission of bag ventilation. The polio wards swarmed with internists, anesthesiologists, head and neck surgeons, physical therapists, experts in laboratory medicine and nurses. The team addressed nutrition and bedsore prevention. A comprehensive triage system facilitated recognition of impending respiratory failure. Ibsen and colleagues even ventured to outlying communities to collect stricken patients and ventilate them en route to Copenhagen. The Bledgam team cared for the mind as they cared for the body: The polio wards featured teachers, books and music.

The coordinated response was prescient. Decades before “cross-functionality” became a management buzzword, the leaders of the respective medical specialties gathered regularly at the Ibsen home for dinner and discussion. Detailed records on every polio admission to Bledgdam Hospital, compiled at Ibsen’s suggestion, facilitated clinical research. Even in 1952, the junior anesthesiologist sought answers in big data.

One-by-one, despite blood clots, pneumonias, bladder infections and other inevitable consequences of prolonged illness, victims weaned from ventilation as their muscle strength improved. There remained, however, a group of patients who were still unable to breathe on their own. In October 1953, well past the one-year anniversary of Vivi Ebert’s rescue, 20 of the original 318 patients treated by Ibsen’s method still required around-the-clock ventilation at Blegdam Hospital. By 1956, 13 patients remained dependent. As the first clinicians to practice modern intensive care medicine, Ibsen, Lassen, Bjørneboe and colleagues encountered the “chronic respirator patient,” an individual that medicine still struggles to serve nearly 70 years later.

Life After Near-Death

“…at the beginning of intensive therapy it was a problem to keep the patient alive—today it has become a problem to let him die.”

-Bjørn Ibsen, 1975

Although the fundamentals had been practiced for centuries, the new discipline of “critical care medicine” blossomed in the wake of the 1952 Copenhagen polio outbreak. Lessons from Copenhagen bore fruit in Stockholm one year later during the next European polio epidemic. Engineers and physicians scrambled to build the first generation of positive pressure ventilators, applying declassified wartime insight on lung physiology and oxygen systems for pilots and sailors. Machines replaced bag-squeezing students.

Modern “intensive care units” or “shock wards” emerged in Copenhagen at the Kommunehospitalet, at the Los Angeles County General Hospital and at the Baltimore City Hospital. Mechanical ventilators, operating by positive pressure, improved survival for once-hopeless conditions such as shock, drug overdose and cardiac arrest. Temporary breathing tubes placed through the mouth soon obviated surgical tracheostomy. This technique of “intubation” made intensive care more accessible.

Of those patients ventilated in early I.C.U.’s, many recovered, some died and others walked a path in between. Ibsen’s persistence in the summer of 1952 gave Vivi Ebert another chance at life. But the incomplete resurrection of many of the era’s intensive care patients sparked new questions. What happens if the patient cannot be weaned from the ventilator? What happens when the body recovers and the mind does not? Does life support benefit all patients? Should intensive care be offered to everyone? The ethical and social weight of these concerns saddled Ibsen with somewhat conflicting roles as proud father and emerging conscience of this new brand of medicine.

In August 1974, he met with Christian Stentoft, a Danish radio journalist, and was presented with the question, “Who helps when a human being is going to pass away?” As related by Preben Berthelsen—a Danish anesthesiologist, intensive care physician and Ibsen scholar—the interview included this exchange:

Stentoft: “Do we prolong the death process?”

Ibsen: “Yes and often times it would be much more humane to give morphine, peace and comfort to patients with no hope of surviving.”

Stentoft: “Have you done that?”

Ibsen: “Yes I have.”

Effectively, Ibsen confessed to removing patients from the ventilator when their illness was, in his opinion, insurmountable. He did not consult the next of kin. “It serves no purpose that no one can die without having spent at least three months hooked up to a respirator.” A risky admission, even for a national hero.

Newsmen pounced. Published excerpts of the interview, as Berthelsen explains, implied that Ibsen sought to euthanize the hopelessly ill. “Patients beyond reach are ‘helped’ to die!” announced Danish headlines. Ibsen was suspended from hospital duties. Tabloids proclaimed him “the first physician who openly supports and participates in active euthanasia.” Jens Møller, the leader of the conservative Christian Peoples’ Party, cried murder. Others echoed his call for criminal charges.

Copenhagen’s chief medical officer, Hans Erik Knipschildt, summoned Ibsen to dissect fact from rumor. The anesthesiologist confirmed that he had removed dying patients from the ventilator and treated them with morphine. But “the main aim,” says Berthelsen, “was to alleviate pain and secure comfort even if it hastened the demise of the patient.” Knipschildt concluded that Ibsen acted reasonably and that his remarks had been interpreted out of context. “It’s of my understanding that if this conversation was provided in its original form, the whole havoc about Bjørn Ibsen’s business could have been avoided,” Knipschildt told the media. Prosecutors declined to press charges. Though stoked by sensationalist journalism, the controversy surrounding the 1974 Ibsen-Stenthoft interview joined a growing international dialogue, including an address from the Pope on life support ethics, scientific acceptance of brain death, and landmark legal decisions that collectively recast traditional constructs of life and death in the age of the ventilator.

George Anesi, an intensivist and expert in intensive care utilization at the University of Pennsylvania, emphasizes: “It took us a while to come to the conclusion that active withdrawal and passive declination, in the face of futility, are ethically equivalent events. This was a turning point that allowed for a more normalization of the idea of withdrawing support. If someone was sick enough that you would not put them on a ventilator if they were not on one, they were sick enough to justifiably remove a ventilator.”

In his later years, Ibsen told his children, “I am not afraid of dying, I am only afraid of how.”

***

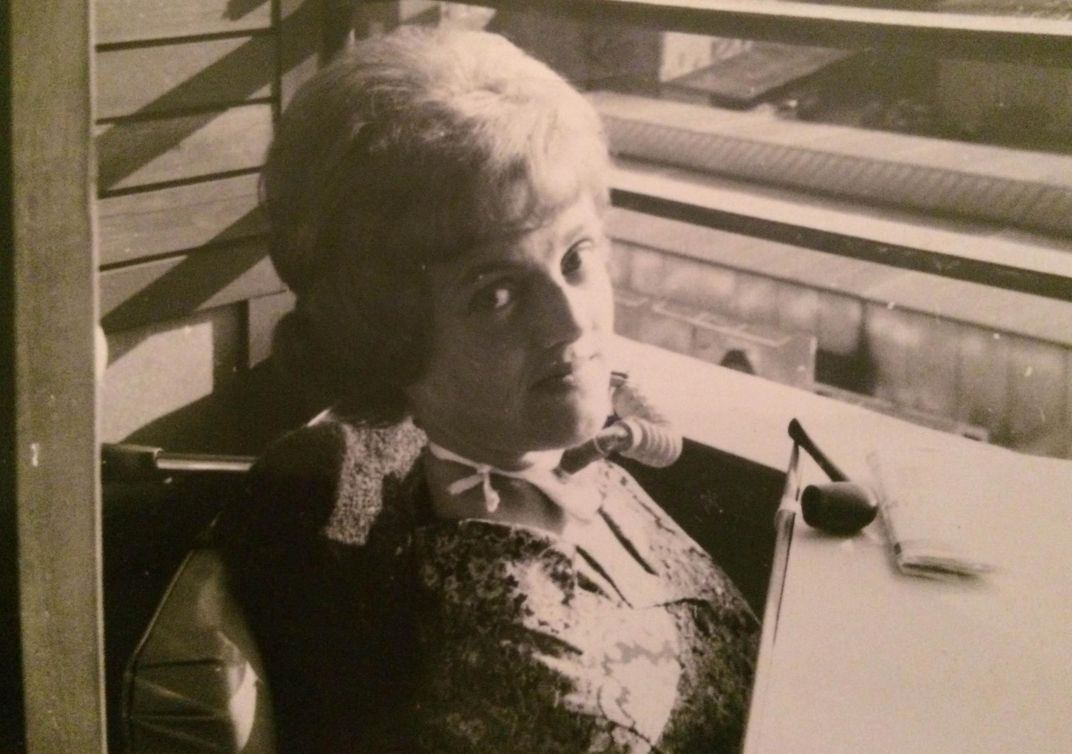

According to her medical chart, Vivi Ebert required continuous mechanical ventilation until January 1953. Quadriplegic, but alive, she left Blegdam in 1959 after a seven-year convalescence. After discharge, she moved with her mother, Karen, and a devoted rough collie named Bobby to an apartment complex for polio survivors. She relied on Karen for most daily needs like eating and toileting. Every evening, Vivi was wheeled to a penthouse unit where she slept on a ventilator under medical supervision.

“Despite her condition she was a very positive person,” says distant cousin Nana Bokelund Kroon Andersen. Optimistic and known for her smile, Vivi eventually completed her education from a wheelchair. Andersen’s mother, Sussi Bokelund Hansen, recalls that Vivi could turn pages in a book, type on a typewriter and paint with a long stick held in her mouth. She married her driver. She was beloved by generations of relatives.

Spirit alone could not shield Vivi from the complications of polio and critical illness. Like most survivors, her life was pockmarked by setbacks. Vivi and her husband eventually separated; not long thereafter, in 1971, she was readmitted to the fever hospital. “Pneumonia” and “sepsis,” determined the doctors, though her mother suspected a broken heart. She died a few days later at the age of 31. It is not clear whether Ibsen maintained contact with his most famous patient; he never spoke to his family about Vivi after their initial encounter in 1952.

In hindsight, Vivi Ebert’s journey after polio was as noteworthy as her August resurrection. Having endured the infection, she lived her remaining days dependent on people and machines to sustain her: too sick to survive on her own, but too well to surrender hope. Before intensive care, this manmade purgatory did not exist. Now termed “chronic critical illness,” this syndrome arises when recovery from catastrophe stops short. Patients with chronic critical illness often develop muscle wasting and weakness, fluid retention, neurologic dysfunction, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, hormone imbalances and increased susceptibility to infection. Its shadow may be life-long and, in retrospect, was visible in polio survivors like Vivi—the world’s first graduates of intensive care.

Today, five to ten percent of all respiratory failure patients, about 100,000 Americans annually, share a similar fate. Of those discharged from the I.C.U. to specialized long-term ventilator rehabilitation facilities, about at least half will die within the year, and fewer than one in ten will ever return home able to walk, eat or dress independently. Older patients or those with a greater number of medical problems may face even tougher odds. Sadly, these statistics have not improved over the last 20 years, though not for lack of trying.

Faced with this understanding, modern critical care physicians must balance hope with reality when counseling the sick. An overly actuarial discussion of I.C.U. outcomes may alienate the patient and engender suspicion that the doctor is prematurely “giving up.” Conversely, skirting altogether the issue of prognosis risks more catheters, more needles and more setbacks, for little prospect of a life independent of machines and hospital walls. And even when physicians do begin these conversations—time pressure, prognostic uncertainty and fear of undermining patient trust are common barriers—not everyone is ready to listen.

On Pandemics Present and Future

Seven decades of scientific and historical examination defused the mystery of the poliovirus. As Ibsen and colleagues learned to bag ventilate, laboratory researchers unraveled the biology of viral growth and transmission. Arrival of the Salk vaccine in 1955 and the Sabin oral vaccine in 1961 halted epidemic polio in the West and laid the foundation for global eradication efforts.

“By their disturbing and upsetting effects,” writes the medical historian G.L. Wackers, “epidemics, like wars, force the display of strengths and weaknesses in the political order of the infested societies.” The events of August 27, 1952, bore the thumbprint of war, urbanization and centuries of biomedical innovation. Out of plague and disaster—more patients than ventilators—emerged a new lifesaving tactic, predicated on applied science and engineering, practiced in real time. “The active approach and the fighting spirit in medicine are wonderful,” Ibsen would remark in the 1970s. But Copenhagen also emphasizes how advances in medicine often trade one problem in the present for another in the future. Even prior to COVID-19, the healthcare system strained under the ethical and financial burdens of this “active approach.”

Over Ibsen’s career, intensive care became a victim of its own success. Bioethical reforms of the latter 20th century, justified and overdue, replaced the physician as arbiter of the ventilator switch with an unflinching commitment to patient autonomy. On the whole, medicine is more humane for it. But with its buffet of tubes and machines, sampled with insufficient consideration of risks versus benefits, intensive care lays bare one disquieting legacy of this transition. The nuance and complexity of this science, vastly evolved since 1952, challenge the expectation that laypersons can make dispassionate, informed decisions—and weigh the implications of incomplete recovery—amid gasping, weakening pulse and the need for immediate action. Bjørn Ibsen recognized this before most.

Many will benefit from intensive care medicine, but its ongoing availability in times of personal or global crisis hinges on careful identification of those who have the most to gain, and the least to lose, from this approach. Improved education and counseling could empower our sickest patients, or their surrogates, to weigh more fully the benefits and risks of medicine’s most heroic therapies. “Increased patient and surrogate autonomy was an appropriate response to paternalistic medical abuses in the 20th century,” Anesi explains, “but true autonomy requires both the freedom to make one’s own decision and the tools to make it an informed decision. We’ve done better with the freedom part than the tools part—most notably, we’ve been short on education to put options in context and limiting options to those that may truly provide benefit and that align with the patient’s values.”

To this end, an effective response to COVID-19—and the inevitable next pandemic—demands grassroots conversations about the realities of life support and the journey after. Nations must also rebuild critical supply chains for ventilators, drugs, protective equipment and healthcare workers, which were undermined by years of myopic cost-cutting and “lean” management practices often by those who will themselves never be asked to face a contagious patient without an N95 mask or to improvise to save a human life. “Just-in-time” allocation of men and material is never more than one misfortune away from shortages and patient harm. Only those naïve to history can expect otherwise.

In this origin story of the modern ventilator, the duality of intensive care medicine comes through: Its defining strength is also its weakness. Through Bjørn Ibsen and the breath-givers who preceded him, pandemic polio taught the first lesson: “Actually, it does not matter what is the source of the patient’s gasping. You simply have to bring his breathing back in order.”

Bradley M. Wertheim is a pulmonary and critical care physician and scientist at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School. He has written for The Atlantic, the Los Angeles Times and peer-reviewed medical journals.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/b1/b4b1ac0e-29df-42f9-92ef-c50f28c20a06/ventilator_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/32/6e32c813-5f41-414e-8779-2e8e82aa1387/ventilator_banner_2.jpg)