How to Resurrect a Lost Language

Piecing together the language of the Miami tribe, linguists Daryl Baldwin and David Costa are creating a new generation of speakers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/b0/f5b0285a-0e29-47a3-9e42-b3c143a425d2/daryl-baldwin-macarthur-foundation.jpg)

Decades ago, when David Costa first started to unravel the mystery of Myaamia, the language of the Miami tribe, it felt like hunting for an invisible iceberg. There are no sound recordings, no speakers of the language, no fellow linguists engaged in the same search—in short, nothing that could attract his attention in an obvious way, like a tall tower of ice poking out of the water. But with some hunting, he discovered astonishing remnants hidden below the surface: written documents spanning thousands of pages and hundreds of years.

For Daryl Baldwin, a member of the tribe that lost all native speakers, the language wasn’t an elusive iceberg; it was a gaping void. Baldwin grew up with knowledge of his cultural heritage and some ancestral names, but nothing more linguistically substantial. “I felt that knowing my language would deepen my experience and knowledge of this heritage that I claim, Myaamia,” Baldwin says. So in the early 1990s Baldwin went back to school for linguistics so he could better understand the challenge facing him. His search was fortuitously timed—Costa’s PhD dissertation on the language was published in 1994.

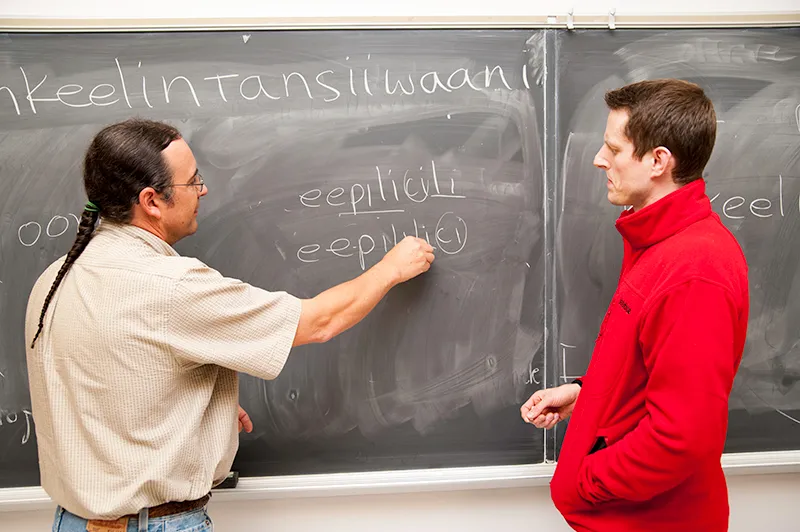

United by their work on the disappearing language, Costa and Baldwin are now well into the task of resurrecting it. So far Costa, a linguist and the program director for the Language Research Office at the Myaamia Center, has spent 30 years of his life on it. He anticipates it’ll be another 30 or 40 before the puzzle is complete and all the historical records of the language are translated, digitally assembled, and made available to members of the tribe.

Costa and Baldwin’s work is itself one part of a much larger puzzle: 90 percent of the 175 Native American languages that managed to survive the European invasion have no child speakers. Globally, linguists estimate that up to 90 percent of the planet’s 6,000 languages will go extinct or become severely endangered within a century.

“Most linguistic work is still field work with speakers,” Costa says. “When I first started, projects like mine [that draw exclusively on written materials] were pretty rare. Sadly, they’re going to become more and more common as the languages start losing their speakers.”

Despite the threat of language extinction, despite the brutal history of genocide and forced removals, this is a story of hope. It’s about reversing time and making that which has sunk below the surface visible once more. This is the story of how a disappearing language came back to life—and how it’s bringing other lost languages with it.

The Miami people traditionally lived in parts of Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin. The language they spoke when French Jesuit missionaries first came to the region and documented it in the mid-1600s was one of several dialects that belong to the Miami-Illinois language (called Myaamia in the language itself, which is also the name for the Miami tribe—the plural form is Myaamiaki). Miami-Illinois belongs to a larger group of indigenous languages spoken across North America called Algonquian. Algonquian languages include everything from Ojibwe to Cheyenne to Narragansett.

Think of languages as the spoken equivalent of the taxonomic hierarchy. Just as all living things have common ancestors, moving from domain down to species, languages evolve in relation to one another. Algonquian is the genus, Miami-Illinois is the species, and it was once spoken by members of multiple tribes, who had their own dialects—something like a sub-species of Miami-Illinois. Today only one dialect of the language is studied, and it is generally referred to as Miami, or Myaamia.

Like cognates between English and Spanish (which are due in part to their common descent from the Indo-European language family), there are similarities between Miami and other Algonquian languages. These likenesses would prove invaluable to Baldwin and Costa’s reconstruction efforts.

But before we get to that, a quick recap of how the Miami people ended up unable to speak their own language. It’s a familiar narrative, but its commonness shouldn’t diminish the pain felt by those who lived through it.

The Miami tribe signed 13 treaties with the U.S. government, which led to the loss of the majority of their homelands. In 1840, the Treaty of the Forks of the Wabash required they give up 500,000 acres (almost 800 square miles) in north-central Indiana in exchange for a reservation of equal size in the Unorganized Indian Territory—what was soon to become Kansas. The last members of the tribe were forcibly removed in 1846, just eight years before the Kansas-Nebraska Act sent white settlers running for the territory. By 1867 the Miami people were sent on another forced migration, this time to Oklahoma where a number of other small tribes had been relocated, whose members spoke different languages. As the tribe shifted to English with each new migration, their language withered into disuse. By the 1960s there were no more speakers among the 10,000 individuals who can claim Miami heritage (members are spread across the country, but the main population centers are Oklahoma, Kansas and Indiana). When Costa first visited the tribe in Oklahoma in 1989, that discovery was a shock.

“Most languages of tribes that got removed to Oklahoma did still have some speakers in the late 80s,” Costa says. “Now it’s an epidemic. Native languages of Oklahoma are severely endangered everywhere, but at that time, Miami was worse than most.”

When Baldwin came to the decision to learn more of the Miami language in order to share it with his children, there was little to draw on. Most of it was word lists that he’d found through the tribe in Oklahoma and in his family’s personal collection. Baldwin’s interest coincided with a growing interest in the language among members of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, which produced its first unpublished Myaamia phrase book in 1997. Baldwin had lists of words taped around the home to help his kids engage with the language, teaching them animal names and basic greetings, but he struggled with pronunciation and grammar. That’s where Costa’s work came in.

“David can really be credited with discovering the vast amount of materials that we work with,” Baldwin says. “I began to realize that there were other community members who also wanted to learn [from them].”

Together, the men assembled resources for other Miami people to learn their language, with the assistance of tribal leadership in Oklahoma and Miami University in southern Ohio. In 2001 the university (which owes its name to the tribe) collaborated with the tribe to start the Myaamia Project, which took on a larger staff and a new title (the Myaamia Center) in 2013.

When Baldwin first started as director of the Myaamia Center in 2001, following completion of his Master’s degree in linguistics, he had an office just big enough for a desk and two chairs. “I found myself on campus thinking, ok, now what?” But it didn’t take him long to get his bearings. Soon he organized a summer youth program with a specific curriculum that could be taught in Oklahoma and Indiana, and he implemented a program at Miami University for tribal students to take classes together that focus on the language, cultural history and issues for Native Americans in the modern world. Baldwin’s children all speak the language and teach it at summer camps. He’s even heard them talk in their sleep using Myaamia.

To emphasize the importance of indigenous languages, Baldwin and others researched the health impact of speaking a native language. They found that for indigenous bands in British Columbia, those who had at least 50 percent of the population fluent in the language saw 1/6 the rate of youth suicides compared to those with lower rates of spoken language. In the Southwestern U.S., tribes where the native language was spoken widely only had around 14 percent of the population that smoked, while that rate was 50 percent in the Northern Plains tribes, which have much lower language usage. Then there are the results they saw at Miami University: while graduation rates for tribal students were 44 percent in the 1990s, since the implementation of the language study program that rate has jumped to 77 percent.

“When we speak Myaamia we’re connecting to each other in a really unique way that strengthens our identity. At the very core of our educational philosophy is the fact that we as Myaamia people are kin,” Baldwin says.

While Baldwin worked on sharing the language with members of his generation, and the younger generation, Costa focused on the technical side of the language: dissecting the grammar, syntax and pronunciation. While the grammar is fairly alien to English speakers—word order is unimportant to give a sentence meaning, and subjects and objects are reflected by changes to the verbs—the pronunciation was really the more complicated problem. How do you speak a language when no one knows what it should sound like? All the people who recorded the language in writing, from French missionaries to an amateur linguist from Indiana, had varying levels of skill and knowledge about linguistics. Some of their notes reflect pronunciation accurately, but the majority of what’s written is haphazard and inconsistent.

This is where knowledge of other Algonquian languages comes into play, Costa says. Knowing the rules Algonquian languages have about long versus short vowels and aspiration (making an h-sound) means they can apply some of that knowledge to Miami. But it would be an overstatement to say all the languages are the same; just because Spanish and Italian share similarities, doesn’t mean they’re the same language.

“One of the slight hazards of extensively using comparative data is you run the risk of overstating how similar that language is,” Costa says. “You have to be especially careful to detect what the real differences are.”

The other challenge is finding vocabulary. Sometimes it’s a struggle to find words that seem like they should be obvious, like ‘poison ivy.’ “Even though we have a huge amount of plant names, no one in the 1890s or 1900s ever wrote down the word for poison ivy,” Costa says. “The theory is that poison ivy is much more common now than it used to be, since it’s a plant that thrives in disturbed habitats. And those habitats didn’t exist back then.”

And then there’s the task of creating words that fit life in the 21st century. Baldwin’s students recently asked for the word for ‘dorm rooms’ so they could talk about their lives on campus, and create a map of campus in Myaamia. Whenever such questions arise, Baldwin, Costa and others collaborate to understand whether the word already exists, if it’s been invented by another language in the Algonquian family (like a word for ‘computer’) and how to make it fit with Myaamia’s grammar and pronunciation rules. Above all, they want the language to be functional and relevant to the people who use it.

“It can’t be a language of the past. Every language evolves, and when a language stops evolving, why speak it?” Baldwin says.

Their approach has been so successful that Baldwin began working with anthropology researchers at the Smithsonian Institution to help other communities learn how to use archival resources to revitalize their lost or disappearing languages. The initiative was developed out of the Recovering Voices program, a collaboration between the National Museum of Natural History, the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and the National Museum of the American Indian. Researchers from each of the institutions aim to connect with indigenous communities around the world to sustain and celebrate linguistic diversity. From this initiative came National Breath of Life Archival Institute for Indigenous Languages. The workshop has been held in 2011, 2013, 2015 and is slated once again for 2017.

According to Gabriela Pérez Báez, a linguist and researcher for Recovering Voices who works on Zapotec languages in Mexico, the workshop has hosted community members from 60 different languages already.

“When I started linguistics in 2001, one of my professors said, ‘You just need to face it, these languages are gonna go and there’s little we can do,’” Báez says. “I do remember at that time feeling like, is this what I want to do as a linguist? Because it looked very gloomy all around.”

But the more she learned about Baldwin and Costa’s work, and the work undertaken by other tribes whose language was losing speakers, the more encouraged she became. She recently conducted a survey of indigenous language communities, and the preliminary results showed that 20 percent of the people who responded belonged to communities whose languages were undergoing a reawakening process. In other words, their indigenous language had either been lost or was highly endangered, but efforts were underway to reverse that. Even the linguistic terms used to describe these languages has changed: what were once talked of as “dead” or “extinct” languages are now being called “dormant” or “sleeping.”

“All of a sudden there’s all these language communities working to reawaken their languages, working to do something that was thought to be impossible,” Báez says. And what’s more, the groups are being realistic with their goals. No one expects perfect fluency or completely native speakers anytime soon. They just want a group of novice speakers, or the ability to pray in their language, or sing songs. And then they hope that effort will continue to grow throughout the generations.

“It’s amazing that people are committing to a process that’s going to outlive them,” Báez says. “That’s why Daryl [Baldwin] is so focused on the youth. The work the Myaamia Center is doing with tribal youth is just incredible. It’s multiplying that interest and commitment.”

That’s not to say Breath of Life can help every language community across the U.S. Some languages just weren’t thoroughly documented, like Esselen in northern California. But whatever resources are available through the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives and the Library of Congress and elsewhere are made available to all the groups that come for the workshop. And the efforts don’t end in the U.S. and Canada, Báez says. Researchers in New Zealand, Australia, Latin America and elsewhere are going back to archives to dig up records of indigenous languages in hopes of bolstering them against the wave of endangerment.

“I’m a very science-y person. I want to see evidence, I want to see tangible whatevers,” Báez says. “But to see [these communities] so determined just blows you away.”

For Baldwin and Costa, their own experience with the Myaamia Project has been humbling and gratifying. There are now living people who speak Myaamia together, and while Costa doesn’t know if what they’re speaking is the same language as was spoken 200 years ago, it’s a language nonetheless. Baldwin even received a MacArthur “genius grant” for his work on the language in 2016.

They don’t want to predict the future of the language or its people; we live in a world where 4 percent of languages are spoken by 96 percent of the population. But both are hopeful that the project they’ve started is like a spring garden slowly growing into something much larger.

“You don’t know what the seed is, but you plant it and you water it,” Baldwin says. “I hope it’s a real cool plant, that it’s got nice flowers.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)