How To Prepare for a Future of Gene-Edited Babies—Because It’s Coming

In a new book, futurist Jamie Metzl considers the ethical questions we need to ask in order to navigate the realities of human genetic engineering

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/6a/566a0101-0f81-4730-b627-3c9696451409/newborns.jpg)

“It really feels to me like the world of science fiction and science fact are, in many ways, converging,” says Jamie Metzl. The polymath would know—he’s an expert on Asian foreign relations who served in the State Department, a futurist who was recently named to the World Health Organization’s advisory committee on human genome editing governance, and yes, the author of two biotech-fueled science-fiction novels. But his newest project, Hacking Darwin, is pure nonfiction. In the book, Metzl sketches out how real-world trends in genetics, technology and policy will lead us to a swiftly approaching future that seems plucked from science fiction but, Metzl argues, is not just plausible but inevitable: a globe where humans have taken charge of our species’ evolution through altering our DNA.

In Hacking Darwin, Metzl sorts through scientific and historic precedent to forecast the far-ranging ramifications of this technological shift, from the shameful popularity of eugenics in the early 20th century to the controversy over the first “test tube baby” conceived through in vitro fertilization more than 40 years ago. Potential side effects for this particular medical marvel may include geopolitical conflict over regulation of genetic enhancement and a torrent of ethical questions that we, Metzl writes, desperately need to consider. Hacking Darwin aims to educate and spark what Metzl calls a “species-wide dialogue on the future of genetic engineering.” Smithsonian.com talked to the futurist and Atlantic Council Senior Fellow about the bold predictions he makes, the ethical quandaries genetic engineering poses and the path forward.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/93/07935a6f-5836-4198-88dc-19f4dd99e25c/jamie_metzl.jpg)

What is the timeline, as you see it, for some of the key technological advances in genetic engineering?

Right now, a person goes to an IVF clinic. They can obviously have their eggs extracted, fertilized and screened for single gene mutation disorders, chromosomal disorders and a small number of traits like eye color and hair color. In 10 years, because more people will have been [genetically] sequenced then, we'll be able to use big data analytics to compare their genetic sequence to their phenotypic information—how those genes are expressed over the course of their lifetimes. We're going to know a lot more about complex genetic disorders and diseases, like the genetic predisposition for heart disease or early-onset familial Alzheimer's. But we're also going to know more about traits that have nothing to do with health status, like height or the genetic component of I.Q. People are going to have that information when making the decisions about which embryos to implant.

Perhaps 10, maybe 20 years after that, we are going to begin entering a world where we will be able to generate very large numbers of eggs from adult stem cells. The larger the number of eggs, the greater the level of choice there will be when selecting which embryo to implant. That would be a fundamental game changer. In that same time frame, and actually even sooner [before 2050], we're going to be able to make a relatively small number of edits to pre-implanted embryos using precision gene editing tools; it's very likely that will be more precise than CRISPR, which is used today.

I certainly think that 40 or 50 years from now, conceiving children in a lab will be the normal way that people in advanced countries conceive their children, and I certainly see ourselves moving in a direction where conception through sex will come to be seen as natural, yet dangerous. Kind of equivalent to not vaccinating your kids today is seen as something that's very natural, and yet taking on an unnecessary risk.

One concern about genetic modification of embryos is that if parents are given the power to choose the traits of their children, their selections might reflect the biases embedded in our society. You bring up the possibility of people selecting a certain sexual orientation or skin pigmentation, or against a disability. How do you think these concerns will be addressed as the technology advances?

Diversity isn't just a nice way to have interesting and productive universities and workplaces. Diversity through random mutation is the sole survival strategy of our species. But for 3.8 billion years of our evolution, diversity has been something that just kind of happened to us, through the Darwinian principle. But now that we are increasingly taking control of our own biology, we are going to have to be mindful of what we mean by diversity, when diversity is a choice. We need to be very mindful of the danger of reducing our population-wide diversity.

We also need to be very careful that in the process of using these technologies, we don’t dehumanize ourselves, our children or others. I meet with many people from the disability community, and people say, 'Hey, my child has Down syndrome, and I love my child. Are you saying that in the future, there won't be very many people—at least in the developed world—who have Down syndrome? Are you making an implicit judgment? Is there something wrong with Down syndrome itself?' And what I always say is that, 'Anybody who exists has an equal right to thrive, and we have to recognize everybody and we have to ensure that everybody who exists has our love and our support and has everything that they need.'

But the question in the future will be different. A future mother, for example, has 15 embryos, and maybe she knows that two of them are carrying genetic disorders that are likely to kill them at a very early age, and maybe one of them will have Down syndrome. And then there are 12 other pre-implanted embryos [that have tested negative for both fatal genetic disorders and Down syndrome], and the question is, if given that choice, how would we think about the potential for carrying on what we see as disabilities? I think when people think about that, maybe they'll say, 'If we select these embryos, and they become babies that have these genetic disorders, and there's a very high likelihood that these disorders will lead to early death, maybe it's not a good idea to implant those embryos.'

We know that's what parents are going to do, because now, in the case of prenatal screening, nearly 100 percent of people [in some countries] in Northern Europe who are doing prenatal screening and receive a diagnosis of Down syndrome are choosing to abort. Even in the United States, which has very different views on these issues than Europe, two-thirds of people make that choice. We're going to have to really be mindful about how we deploy these technologies that can enhance people’s health and their children’s health and well-being, but doing so in a way that doesn’t diminish our humanity or diminish our love and respect for people around us who already exist.

Hacking Darwin: Genetic Engineering and the Future of Humanity

From leading geopolitical expert and technology futurist Jamie Metzl comes a groundbreaking exploration of the many ways genetic-engineering is shaking the core foundations of our lives ― sex, war, love, and death.

What about traits that aren't necessarily linked to health and well-being but still have some genetic determinants?

You mentioned skin color. It is all really sensitive stuff, and there will be some societies that will say, 'This is so sensitive, we're going to make it illegal.' But in many societies, they will choose based on the information that's available to them. If they're only 15 embryos, it's going to be very difficult to pick for everything. But if there are 10,000 embryos, you do get a lot of optionality. All of these things will be choices, and we can pretend that's not going to be the case, but that's not going to help us. What we have to do is say: 'We know we have a sense of where our world is heading, and what are the values that we want to deploy in that future?' And if we're imagining those values in the future, we better start living those values now so that when this radically different future arrives, we'll know who we are and what we stand for.

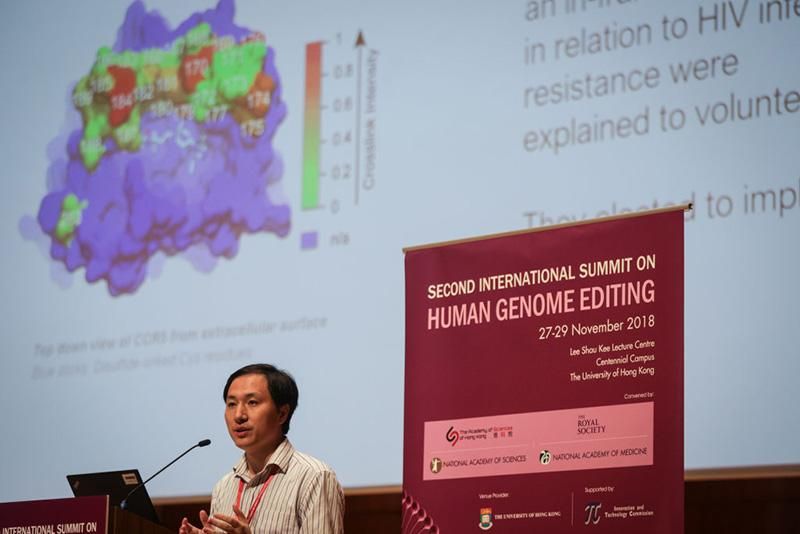

Let's talk about the CRISPR twins. What does the birth of the first genetically modified humans, who will pass on these genetic changes to their children, and also the backlash to the announcement of their birth, tell us about the future of genetic-engineering embryos?

Before this happened, I felt very confident that this was going to happen, and it was going to happen in China. The process that Dr. He [Jiankui] used, in my mind, was extremely unethical. He was extremely secretive. The consent of the parents was extremely flawed. His application to the hospital ethics board was to an ethics board not of the hospital where he was actually working but another hospital where he was an investor. And the intervention wasn't to cure or even prevent an imminent disease, but to confer an enhancement of an increased resistance to HIV. Had Dr. He not done what he did…two or five years from now, we would've been having the same conversation about a better first application [of CRISPR technology on embryos that were then carried to term], probably to gene edit a pre-implanted embryo that was a dominant carrier of a dangerous or deadly Mendelian disease. That would have been a better first step.

Having said that, this misstep and this controversy woke people up. It made people realize that is real, this isn't science fiction. This is imminent, and we don't have time to wait to have an inclusive global conversation on the future of human genome editing. We don't have time to wait to start really working actively to set up the ethical and regulatory and legal framework that can help make sure that we can optimize the upside and minimize any potential harms of these powerful technologies.

You write about the U.S. and China being in a neck-and-neck race over technological and genetic innovation: “Whichever society makes the right bet will be poised to lead the future of innovation.” Which country do you think is poised to make that winning bet right now, and why?

Basic science in the United States is still much better than it is in China and in most every other country in the world. But China has a national plan to lead the world in major technologies by 2050 and certainly genetics and biotech are among them. They have a huge amount of money. They have an extremely talented population and some world-class scientists. And while China has some pretty well-written laws, there is a Wild West mentality that pervades a lot of the business and science community.

So while the science itself will probably be still a little bit more advanced on average in the United States than in China, the applications of that science will be far more aggressive in China than in the United States. We've already seen that. The second issue is that genomics is based on big data analytics, because that's how we gain insights about complex genetic diseases, disorders and traits. We have three models. We have the European model of very high levels of privacy. We have the China model of very low levels of privacy, and the U.S. model in the middle. Each one of those jurisdictions is making a bet on the future.

It is my belief that the countries with the biggest, the largest, most open, high-quality data sets will be best positioned to secure national competitive advantages in the 21st century, and China has its eyes set on that goal more certainly than the United States does.

What role should historians and the humanities play in the burgeoning field of genetic editing?

The science of genetic engineering is racing forward at an incredible rate. But all technologies are themselves agnostic. They can be used for good or for bad or for everything in between. Talking about ethics and values, talking about the whole set of issues which we generally file into the category of the humanities has to be at the very core of what we are doing, and we need to make sure that there is a seat at the table for people of different backgrounds and different persuasions. If we see this just as a scientific issue, we're going to miss the essence of what it really is, which is a societal issue.

And are we doing a good job of that right now?

We're doing a terrible job. Right now, those data pools that we are using to make predictions are predominately white, primarily because the United Kingdom has the most usable genetic data set. People who are being sequenced will come to better reflect society as a whole, but there's a period now where that will not be the case. All of these issues of diversity, of inclusion, we really need to see them as absolutely essential. That's one of the reasons why I've written the book. I want people to read the book and say, ‘Alright, now I know enough that I can enter the conversation.’ What we are talking about is the future of our species and that should be everybody's business.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.