Could Immunotherapy Lead the Way to Fighting Cancer?

A new treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer is offering hope to patients with advanced disease

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/45/664577b2-b79a-4017-a93e-4eec878564f6/apr2018_a02_futureofhealth.jpg)

In the morning of June 24, 2014, a Tuesday, Vanessa Johnson Brandon awoke early in her small brick house in North Baltimore and felt really sick. At first, she thought she had food poisoning, but after hours of stomach pain, vomiting and diarrhea, she called her daughter, Keara Grade, who was at work. “I feel like I’m losing it,” said the woman everyone called Miss Vanessa. Keara begged her to call an ambulance, but her mother wanted to wait until her husband, Marlon, got home so he could drive her to the emergency room. Doctors there took a CT scan, which revealed a large mass in her colon.

Hearing about the mass terrified her. Her own mother had died of breast cancer at the age of 56. From that point on, Miss Vanessa, then 40, became the matriarch of a large family that included her seven younger siblings and their children. Because she knew how it felt to have a loved one with cancer, she joined a church ministry of volunteers who helped cancer patients with chores and doctor visits. As she prepared meals for cancer patients too weak to cook for themselves, she couldn’t know that the disease would one day come for her, too.

The ER doctors told Miss Vanessa she wouldn’t get the results of follow-up tests—a colonoscopy and a biopsy—until after the July 4 weekend. She had to smile her way through her own 60th birthday on July 6, stoking herself up on medications for nausea and pain to get through the day.

At 9:30 the next morning, a doctor from the Greater Baltimore Medical Center called. He didn’t say, “Are you sitting down?” He didn’t say, “Is there someone there with you?” Later Miss Vanessa told the doctor, who was on the young side, that when he delivers gut-wrenching news by telephone, he should try to use a little more grace.

It was cancer, just as Miss Vanessa had feared. It was in her colon, and there also was something going on in her stomach. The plan was to operate immediately, and then knock out whatever cancer still remained with chemotherapy drugs.

Thus began two years of hell for Miss Vanessa and her two children—Keara, who is now 45, and Stanley Grade, 37—who live nearby and were in constant contact with their mother and her husband. The surgery took five hours. Recovery was slow, leading to more scans and blood work that showed the cancer had already spread to the liver. Her doctors decided to start Miss Vanessa on as potent a brew of chemotherapy as they could muster.

Every two weeks, Miss Vanessa underwent three straight days of grueling chemo, administered intravenously at her home. Keara and her two teenage sons came around often to help out, but the older boy would only wave at Miss Vanessa from the doorway of her bedroom as he rushed off to another part of the house. He just couldn’t bear to see his grandmother so sick.

Miss Vanessa powered on for 11 months, visualizing getting better but never really feeling better. Then, in July 2015, the doctor told her there was nothing more he could do for her.

“My mom was devastated,” Keara says. Keara told her mother not to listen to the doctor’s dire prediction. “I said to her, ‘The devil was a liar—we are not going to let this happen.’”

So Keara—along with Miss Vanessa’s husband, brother and brother’s fiancée—started Googling like mad. Soon they found another medical center that could offer treatment. But it was in Illinois, in the town of Zion—a name Miss Vanessa took as a good omen, since it was also the name of her 5-year-old grandson. In fact, just a few days earlier little Zion had asked his grandmother if she believed in miracles.

A Cure Within: Scientists Unleashing the Immune System to Kill Cancer

Based entirely on interviews with the investigators, this book is the story of the immuno-oncology pioneers. It's a story of failure, resurrection, and success. It's a story about science, it's a story about discovery, and intuition, and cunning. It's a peek into the lives and thoughts of some of the most gifted medical scientists on the planet.

The family held a fund-raiser for Stanley to get on a plane to Chicago with his mother every two weeks, drive her to Zion and stay with her at the local Country Inn & Suites hotel for three days of outpatient chemotherapy. It felt like a replay of her treatment in Baltimore—worse, since the drugs were delivered in a hotel instead of in her bedroom, and the chemotherapy caused nerve damage that led to pain, tingling and numbness in Miss Vanessa’s arms and legs. And then, in May 2016, the Illinois doctor, too, said there was nothing more he could do for her. But at least he offered a sliver of hope: “Go get yourself on a clinical trial.” Weeks later, desperate, Miss Vanessa and Keara grew hopeful about a treatment involving mistletoe. They attended an information session at a Ramada extolling the plant extract’s anti-cancer properties. But when they learned that it would cost $5,000 to enroll, they walked out dejected.

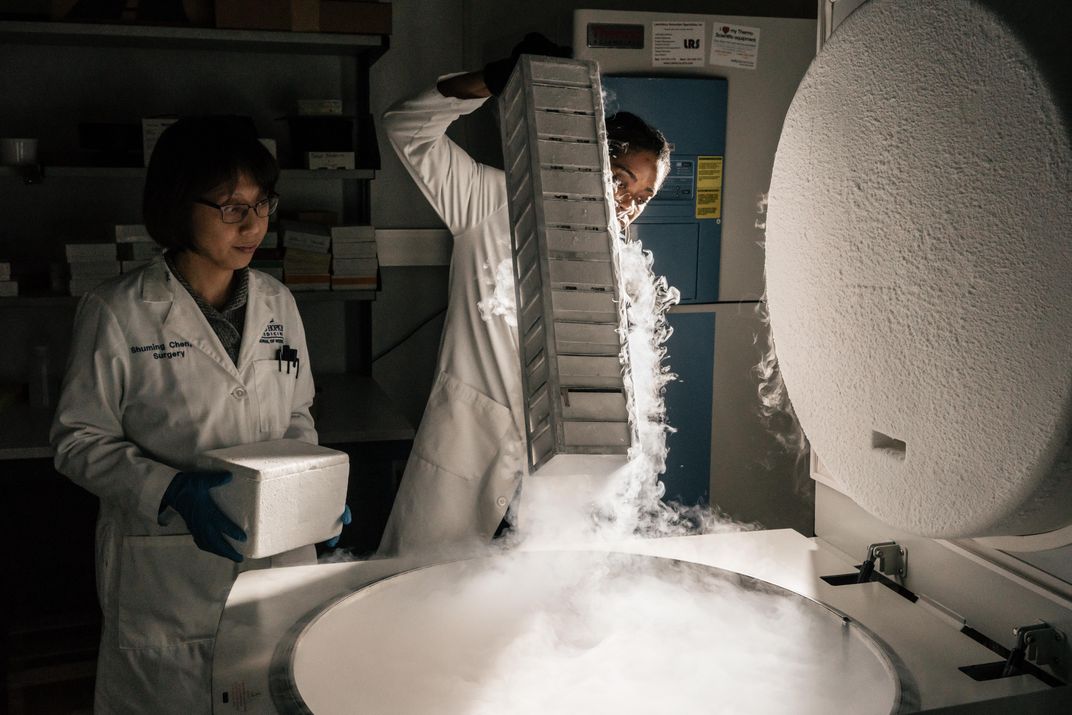

Finally, Miss Vanessa’s husband stumbled onto a website for a clinical trial that seemed legit, something underway at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, just down the road from their home. This new treatment option involved immunotherapy, something markedly different from anything she had gone through. Rather than poisoning a tumor with chemotherapy or zapping it with radiation, immunotherapy kills cancer from within, recruiting the body’s own natural defense system to do the job. There are a number of different approaches, including personalized vaccines and specially engineered cells grown in a lab. (See “A Cancer Vaccine?” and “A DNA-Based Attack”)

The trial at Hopkins involved a type of immunotherapy known as a checkpoint inhibitor, which unlocks the power of the immune system’s best weapon: the T-cell. By the time Miss Vanessa made the call, other studies had already proved the value of checkpoint inhibitors, and the Food and Drug Administration had approved four of them for use in several cancers. The Hopkins researchers were looking at a new way of using one of those drugs, which didn’t work at all for most patients but worked spectacularly well for some. Their study was designed to confirm earlier findings that had seemed almost too good to be true.

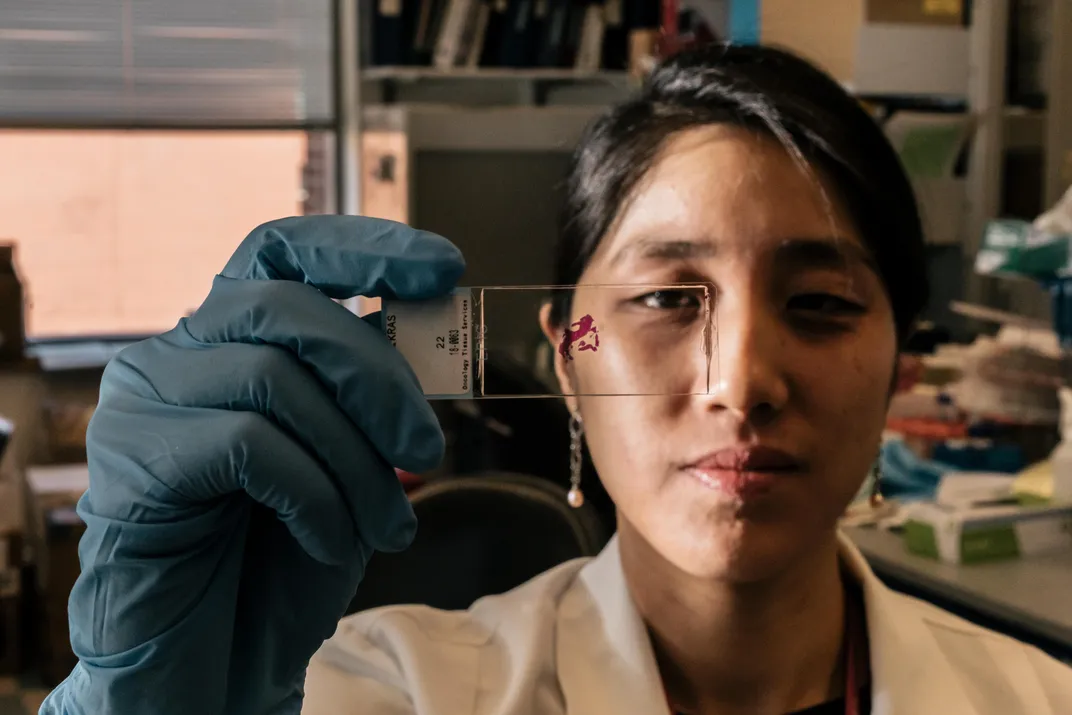

“With the very first patient who responded to this drug, it’s been amazing,” says Dung Le, a straight-talking Hopkins oncologist with long dark hair and a buoyant energy. Most of her research had been in desperately ill patients; she wasn’t used to seeing her experimental treatments do much good. “When you see multiple responses, you get super-excited.”

When Miss Vanessa paid her first visit to Le in August 2016, the physician explained that not every patient with advanced colon cancer qualified for the trial. Investigators were looking for people with a certain genetic profile that they thought would benefit the most. It was a long shot—only about one person in eight would fit the bill. If she had the right DNA, she could join the trial. If she didn’t, she would have to look elsewhere.

About a week later, Miss Vanessa was in her kitchen, a cheery room lined with bright yellow cabinets, when her telephone rang. Caller ID indicated a Hopkins number. “I didn’t want anyone else to call you but me,” said the study’s principal investigator, Daniel Laheru. He had good news: her genes “matched up perfectly” with the criteria for the clinical trial. He told her to come in right away so they could get the blood work done, the paperwork signed and the treatment started. Miss Vanessa recalls, “I cried so hard I saw stars.”

**********

The trial was part of a string of promising developments in immunotherapy—an apparent overnight success that was actually more than 100 years in the making. Back in the 1890s, a New York City surgeon named William Coley made a startling observation. He was searching medical records for something that would help him understand sarcoma, a bone cancer that had recently killed a young patient of his, and came upon the case of a house painter with a sarcoma in his neck that kept reappearing despite multiple surgeries to remove it. After the fourth unsuccessful operation, the house painter developed a severe streptococcus infection that doctors thought would kill him for sure. Not only did he survive the infection, but when he recovered, the sarcoma had virtually disappeared.

Coley dug deeper and found a few other cases of remission from cancer after a streptococcus infection. He concluded—incorrectly, it turned out—that the infection had killed the tumor. He went around promoting this idea, giving about 1,000 cancer patients streptococcus infections that made them seriously ill but from which, if they recovered, they sometimes emerged cancer-free. He eventually developed an elixir, Coley’s Toxins, which was widely used in the early 20th century but soon fell out of favor as radiation and then chemotherapy began to have some success in treating cancer.

Then, in the 1970s, scientists looked back at Coley’s research and realized it wasn’t an infection that had killed the house painter’s tumor; it was the immune system itself, stimulated by the bacterial infection.

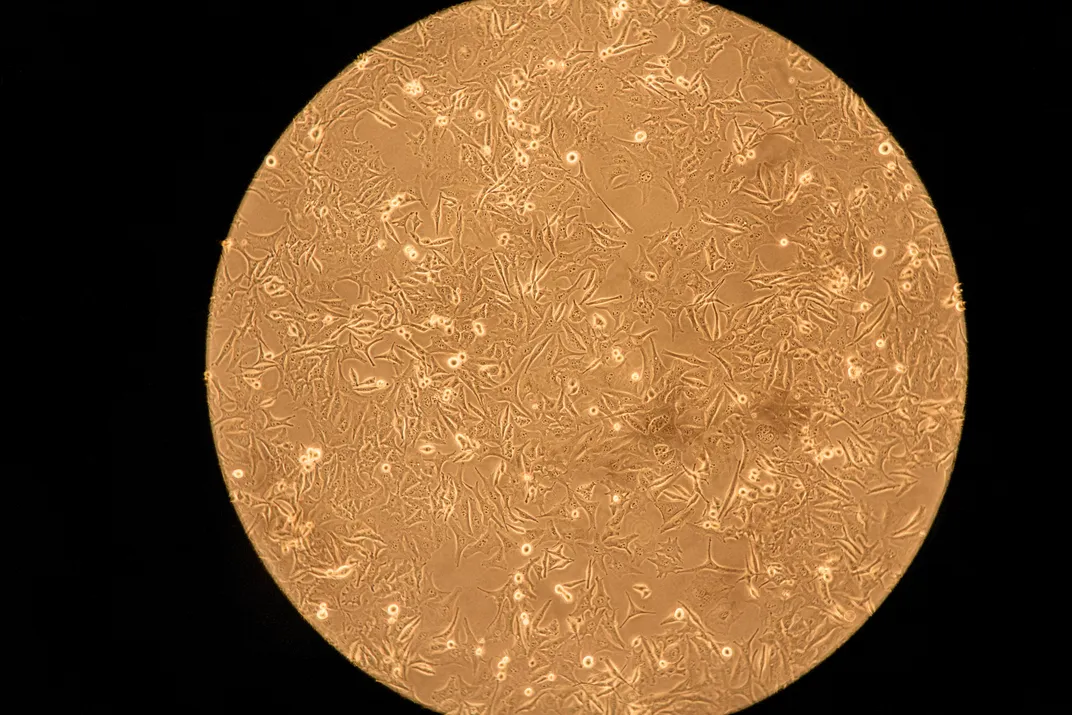

In a healthy body, T-cells activate their weaponry whenever the immune system detects something different or foreign. This might be a virus, a bacterium, another kind of disease-causing agent, a transplanted organ—or even a stray cancer cell. The body continuously generates mutated cells, some of which have the potential to turn cancerous, but current thinking is that the immune system destroys them before they can take hold.

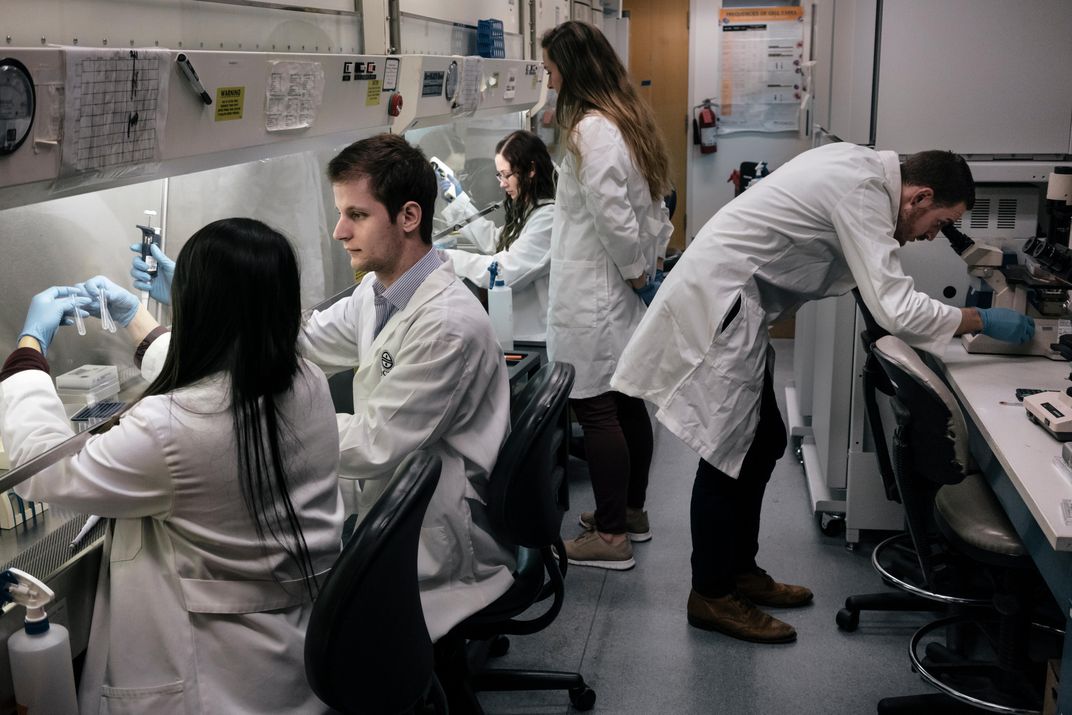

Once scientists recognized the cancer-fighting potential of the immune system, they began to look for ways to kick it into gear, hoping for a treatment that was less pernicious than chemotherapy, which often uses poisons so toxic the cure may be worse than the disease. This immune-based approach looked good on paper and in lab animals, and showed flashes of promise in people. For instance, Steven Rosenberg and his colleagues at the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute made headlines when they removed a patient’s white blood cells, activated them in the lab with the immune system component known as interleukin-2, and infused the cancer-fighting cells back into the patient in hopes of stimulating the body to make a better supply of cancer-fighting cells. Rosenberg ended up on the cover of Newsweek, where he was hailed for being on the cusp of a cancer cure. That was in 1985. The FDA did approve interleukin-2 for adults with metastatic melanoma and kidney cancer. But immunotherapy remained mostly on the fringes for decades, as patients continued to go through rounds of chemotherapy and radiation. “We’ve been curing cancer in mice for many, many years . . . but the promise was unfulfilled for a very long time in people,” says Jonathan Powell, associate director of the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute at Hopkins.

Indeed, many cancer experts lost faith in the approach over the next decade. “Nobody believed in immunotherapy except our own community,” says Drew Pardoll, the director of the BKI. The lack of support was frustrating, but Pardoll says it did have one salutary effect: It made immunotherapy more collegial and less back-biting than a lot of other fields of science. “When you’re a little bit ostracized I think it’s just a natural part of human nature...to sort of say, ‘Well, look, our field is going to be dead if we don’t work together, and it shouldn’t be about individuals,’” Pardoll said. He calls the recent explosion of successes “sort of like Revenge of the Nerds.”

In keeping with this collaborative spirit, immunotherapy researchers from six competing institutions have formed a cover band known as the CheckPoints, which performs at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and in other venues. The band’s harmonica player, James Allison of the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, helped set immunotherapy on its current course with his work on checkpoint inhibitors in 1996, when he was at Berkeley. He was the first to prove that blocking the checkpoint CTLA-4 (shorthand for “cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen”) with an antibody would generate an anti-tumor response. As Pardoll puts it, once Allison demonstrated that first checkpoint system, “we had molecular targets. Before that, it was a black box.”

The checkpoint system, when it’s working as it should, is a simple one: invader is detected, T-cells proliferate. Invader is destroyed, T-cells are deactivated. If T-cells were to stay active without an invader or a rogue cell to fight, they could create collateral damage to the body’s own tissues. So the immune system contains a braking mechanism. Receptors on the surface of the T-cells look for binding partners on the surfaces of other cells, indicating that those cells are healthy. When these receptors find the proteins they’re looking for, they shut the T-cells down until they spot a new invader.

Cancer cells are able to do their damage partly because they co-opt these checkpoints—in effect, hacking the immune system by activating the brakes. This renders the T-cells impotent, allowing the cancer cells to grow unimpeded. Now scientists are figuring out how to put up firewalls that block the hackers. Checkpoint inhibitors deactivate the brakes and allow the T-cells to get moving again. This lets the body kill off the cancer cells on its own.

Suzanne Topalian, who is Pardoll’s colleague at the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute (and also his wife), played a key role in identifying another way the immune system could be used to fight cancer. After working as a fellow in Rosenberg’s lab, she became the head of her own NIH lab in 1989 and moved to Johns Hopkins in 2006. At Hopkins, she led a group of investigators who first tested drugs blocking the immune checkpoint receptor PD-1—short for “programmed death-1”—and the proteins that trigger it, PD-L1 and PD-L2.

In 2012, Topalian shared some highly anticipated findings at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. In a trial of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab, a high proportion of the 296 subjects had shown “complete or partial response”: 28 percent of those with melanoma, 27 percent of those with kidney cancer, and 18 percent of those with non-small-cell lung cancer. These responses were remarkable, considering that the patients all had advanced cancers and had not responded to other treatments. Many had been told before the trial that they were weeks or months away from death. In two-thirds of the patients, the improvements had lasted for at least one year.

Topalian’s talk came after a presentation by Scott Tykodi from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, who described another study with similarly impressive results. Later that day, the New York Times quoted an investment adviser saying checkpoint inhibitors “could be the most exciting clinical and commercial opportunity in oncology.”

**********

Still, ToPalian was mystified by something. In the process of testing a particular checkpoint inhibitor, she and her colleagues had found that some patients responded much more dramatically than others. Colon cancer was especially puzzling. In two trials, Topalian and her colleagues had treated a total of 33 patients with advanced colon cancer with a PD-1 inhibitor. Of those, 32 had had no response at all. But early in the first trial, there was one patient who had a complete tumor regression that lasted several years. With results like these—one success, 32 failures—many scientists might have dismissed the drug as useless for advanced colon cancer. But Topalian kept wondering about that one patient.

Sometimes she would muse about that patient with Pardoll. (They have been married since 1993 and run collaborating labs at the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute, where Topalian is also an associate director.) Pardoll’s thoughts turned to a Hopkins colleague: Bert Vogelstein, one of the world’s leading experts on cancer genetics, and a specialist in colon cancer. “Let’s go talk to Bert,” Pardoll suggested to Topalian. This was in early 2012.

So the couple, along with a few lab mates, took the elevator one flight up from Pardoll’s lab to Vogelstein’s. They described their recent work to the people up there, including their odd finding of the single cancer patient who responded to a checkpoint inhibitor.

“Was the patient’s tumor MSI-high ?” asked Luis Diaz, a cancer geneticist then in Vogelstein’s research group.

MSI stands for microsatellite instability. A high score would indicate that the patient’s tumor had a defect in the DNA proofreading system. When that system functions correctly, it winnows out errors that occur during DNA replication. When it fails, a bunch of mutations accumulate in the tumor cells. From an immunological point of view, a high “mutation load” could be helpful, since it would make cancer cells easier for the immune system to recognize as foreign—almost as if the tumor cells had a “hit me” sign pinned on them.

Topalian contacted the mystery patient’s Detroit-based oncologist, asking for the tumor’s MSI. Sure enough, it was high. Pardoll calls this the study’s “eureka moment.”

The researchers went on to confirm what the geneticists had suspected: the genetic profile known as “MSI-high” makes tumors extraordinarily responsive to checkpoint inhibitors. Only about 4 percent of all advanced solid tumors are MSI-high, but because roughly 500,000 patients in the U.S. are diagnosed with advanced cancer each year, that means about 20,000 could benefit. The genetic profile is most common in endometrial cancer, of which about 25 percent are MSI-high. It is quite rare in other cancers, such as those of the pancreas and breast. Colon cancer falls into the middle range: about 10 to 15 percent of all colon cancers are MSI-high.

In May 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the treatment developed at the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute to target MSI-high patients. Pembrolizumab, sold under the commercial name Keytruda, had already been approved for other specific cancer types. (It became famous in 2015 when former President Jimmy Carter used it to recover from metastatic melanoma that had spread to his liver and brain.) But based on the results of the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute study, the FDA made Keytruda the first drug ever to be approved for all tumors with a particular genetic profile—regardless of where they showed up in the body.

“This is a complete paradigm shift,” says Pardoll. With this historic step, he adds, the FDA has made checkpoint inhibitors “the first cancer-agnostic approach to treatment.”

**********

Immunotherapy is poised to become the standard of care for a variety of cancers. The work being done now is forcing a reconsideration of basic tenets of clinical oncology—for instance, whether surgery should be a first line of treatment or should come after drugs like Keytruda.

Many questions still remain. Elizabeth Jaffee, a member of the “cancer moonshot” panel convened by then-Vice President Joseph Biden in 2016, says she’s conscious of the danger of overselling a treatment. While the effect of checkpoint inhibitors can be “exciting,” she says, “you have to put it in perspective. A response doesn’t mean they’re cured. Some may have a year of response,” but the cancer might start growing again.

The treatments can also have troubling side effects. When T-cells are unleashed, they can misidentify the patient’s own cells as invaders and attack them. “Usually the side effects are low-grade rashes or thyroiditis or hypothyroidism,” Le says. Generally, they can be controlled by taking the patient off immunotherapy for a while and prescribing steroids.

Sometimes, though, the immune system’s reaction can inflame the lungs, colon, or joints or shut down particular organs. A patient can get treated for cancer and come out with rheumatoid arthritis, colitis, psoriasis or diabetes. The most extreme side effects “are high-risk and fatal,” Le says. And they can sometimes flare up without warning—even weeks after the immunotherapy has stopped.

“We had a patient recently who had a complete response”—that is, the cancer was pretty much gone—“who had a fatal event while off therapy,” Le told me. It’s very rare for such a serious side effect to occur, says Le. “Most patients don’t get those things, but when they do, you feel awful.”

Another hurdle is that the six checkpoint-inhibitor drugs now on the market work on only two of the checkpoint systems, either CTLA-4 or PD-1. But the T-cell has at least 12 different brakes, as well as at least 12 different accelerators. The particular brakes and accelerators required to fight off the disease might be different from one cancer type to another, or from one patient to another. In short, there are a lot of possibilities that haven’t yet been thoroughly investigated.

More than 1,000 immunotherapy trials are now underway, most of them driven by pharmaceutical companies. Many of the treatments they’re testing are different proprietary variations of similar drugs. The “cancer moonshot” program—now called Cancer Breakthroughs 2020—is hoping to streamline this research by creating a Global Immunotherapy Coalition of companies, doctors and research centers. With all the money to be made, though, it might prove difficult to turn competition into cooperation. The nerds aren’t a band of outsiders anymore.

Sean Parker, the Silicon Valley entrepreneur, is trying a more open-source approach. Parker rose to fame in 1999 when he co-founded the free song-swapping platform Napster. So it’s no surprise that he believes sharing information is crucial to moving immunotherapy forward. In 2016, he launched the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy with $250 million in funding from his own foundation. His goal is to collect ongoing data from the six major cancer centers in his consortium, plus individuals at several other centers. The parties sign agreements that give them ownership of their own work, but let other researchers see certain anonymized information they gather.

The Parker Institute’s CEO, Jeffrey Bluestone, is an immunologist at the University of California, San Francisco who is also involved in research on Type 1 diabetes and studies immune tolerance in organ transplantation. With his understanding of how the immune system can backfire, he’s been particularly instrumental in finding ways to activate T-cells without causing dangerous side effects. In a 2016 speech at the annual tech conference Dreamforce, Bluestone called the immune system “an intelligent technology platform that is there for us to decode, and ultimately, utilize to beat cancer. Unlike the static, brute force attacks we’ve attempted on cancer in the past, this is a dynamic system that can out-evolve the tumor.”

Topalian also sees large databanks as a key part of immunotherapy’s future. “That way, you can connect data about a tumor biopsy with clinical characteristics of that patient—for instance, how old they are, and how many other treatments they’d had before the biopsy. You can also link in DNA testing, immunological markers, or metabolic markers in a tumor. The vision is that all of this data, emanating from a single tumor specimen, could be integrated electronically and available to everyone.”

Meanwhile, Topalian is continuing to work with Hopkins experts in genetics, metabolism, bioengineering and other areas. One of her colleagues, Cynthia Sears, recently received a grant to study biofilms—the colonies of bacteria that grow in the colon and can either promote or prevent cancer growth. Sears is looking at how a particular “tumor microbial environment” affects the way a patient responds—or fails to respond—to cancer immunotherapy.

“The immune system is the most specific and powerful killing system in the world,” says Pardoll, summing up the state of immunotherapy in early 2018. “T-cells have an amazingly huge diversity, and 15 different ways to kill a cell. The basic properties of the immune system make it the perfect anti-cancer lever.” But science won’t be able to fully mobilize that system without the help of myriad specialists, all working from different angles to piece together the incredibly complex puzzle of human immunity.

**********

On a frigid Saturday morning in January, I met Miss Vanessa in her immaculate living room. “It’s been a journey,” she told me. “And with each step, I’m just so grateful that I’m still living.”

Miss Vanessa, who will turn 64 in July, had assembled a posse to join our conversation. It included her aunt, her next-door neighbor, her best friend, and her children, Keara and Stanley. On a dining chair, keeping close watch on his grandmother, was Keara’s 16-year-old son Davion; sprawled across the staircase that led up to the bedrooms was her 20-year-old son Lettie. Everyone had come to make sure I understood how tough Miss Vanessa is, and how loved.

Today, after a year and a half of treatment with Keytruda, Miss Vanessa’s tumors have shrunk by 66 percent. She still tires easily, and she has trouble walking due to the nerve damage caused by her earlier rounds of chemotherapy. She says her feet feel as if she’s standing in sand. But she’s deeply grateful to be alive. “I’m on a two-year clinical trial, and I asked Dr. Le what’s going to happen when the two years is up,” Miss Vanessa told me. “She said, ‘I got you, you’re good, we’re just going to keep things going as is.’” According to Miss Vanessa, Le told her to focus on spending time with the people she loves, doing the things she loves to do.

For Miss Vanessa, that means cooking. These days Keara has to do a lot of the prep work, because the nerve damage also affected Miss Vanessa’s hands, making it hard for her to wield a knife or vegetable peeler. She wears gloves to grab ingredients from the refrigerator—the nerve damage again, which makes her extremities highly sensitive to cold. Sometimes in the middle of making a meal, she needs to go lie down.

Still, Miss Vanessa told me she thinks of every day as a blessing, and listed the things she has been lucky enough to witness—things she’d feared, just a few years ago, she would never live to see. “I’m here to see Lettie graduate from college,” she said. “I’m here to see Davion go into a new grade. I’m here to watch Zion start kindergarten...” She trailed off, hardly daring to think about the milestones that await Zion’s younger brother and sister, ages 1 and 2.

“When it’s your time, it’s your time—you can’t change that,” said Stanley, gazing at his mother. “Everybody knows you live to die. But I don’t think it’s her time.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.