In the Canary Islands, Tiny El Hierro Strives for Energy Independence

A photojournalist goes behind the scenes at a hybrid power station that could help the island reach its goal to be powered entirely by renewables

El Hierro, the smallest and most isolated of the Canary islands, rises almost 5,000 feet out of the Atlantic ocean, about 250 miles west of the Moroccan coast. Known for its quiet atmosphere, marine and coastal habitats, and biodiversity, the spot was named an UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 2000.

Now, the locale is putting itself on the map for another reason. It is trying to become the world's first energy self-sufficient island, fulfilling a dream that began in 1997, when the local council approved the El Hierro Sustainable Development Plan, which among other things bet on a new, groundbreaking energy model. (Samso, an island in Denmark, is powered solely by renewables, but El Hierro could reach this distinction without ever having been connected to an energy grid.)

El Hierro relies on Gorona del Viento, a two-year-old hybrid power station built on the southeastern part of the island, which generates energy using both wind and water. Five 213-feet tall windmills with blades spanning 115 feet wide stand on a hill near Valverde, the capital. They are capable of supplying a total of 11.5 megawatts of power, more than enough to satisfy the 7-megawatt peaks of demand that this island of almost 11,000 inhabitants can have. The spare energy is used to pump water from a low reservoir to a high one on the grounds of the power station.

“This system of water reservoirs functions like a water battery that keeps the electric energy that is being generated by the windmills stored in the form of potential gravitational energy in the upper reservoir,” says Juan Gil, chief engineer of Gorona del Viento. “When there is no wind, the water is released back to the lower reservoir where a group of turbines generate electricity like a typical hydroelectric power station.”

According to Juan Pedro Sánchez, an engineer and CEO of Gorona del Viento, the young power station is still in a testing phase. “We want to be sure that the energy supply never fails, so we are being conservative and very careful in the beginning,” he says. “Nowadays, when the weather helps, we can go for several days supplying between 80 and 90 percent of the energy needs of the island.” This July, the station managed to supply 100 percent of the demand during a period of 55 hours. Over the course of last February, Gorona del Viento supplied 54 percent of the island's total demand. “Within a year we expect to be supplying between 60 and 70 percent of the total monthly demand,” Sánchez says.

Until recently, El Hierro was powered by generators fueled by diesel brought by boat from Tenerife, the largest and most populated of the Canary Islands. For every hour that Gorona del Viento powers the island, 1.5 tons of diesel are saved. The council of El Hierro estimates that every year operations at Gorona del Viento will reduce the island's emissions by 18,700 metric tons of carbon dioxide and 400 metric tons of nitrogen oxides.

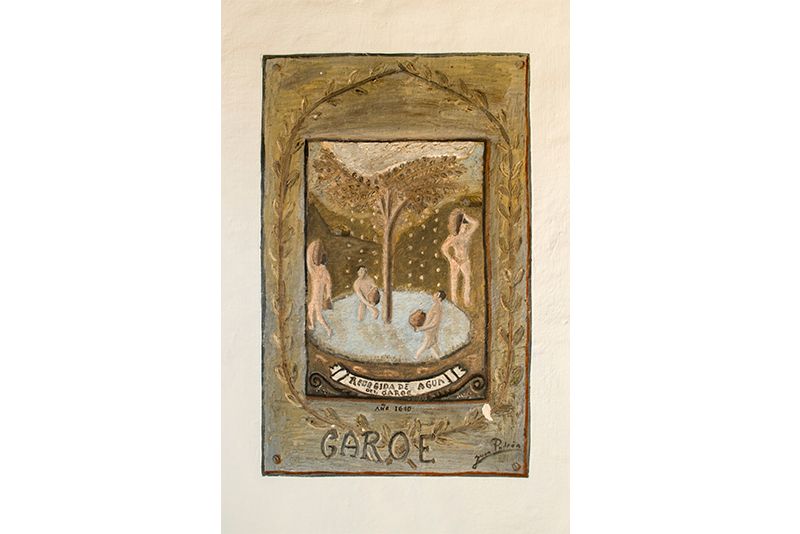

Historically, the geographic conditions of El Hierro, as a remote island, have made it a training ground for self-sufficiency. In ancient times, its people had to find ways of getting water during drought. The orography of the island is such that fog often settles in the hills. The island’s inhabitants discovered a method for “milking the fog” using a tree, regarded as sacred, called garoé. When condensation forms, water drops on the leaves turn to small trickles, which are then collected in underground cavities dug by the locals. Nowadays some local peasants still use the same method, while others modernize the technique a bit by using dense plastic nets and big water tanks to increase the amount of water they collect.

One can't help to think that maybe this early ingenuity and can-do spirit on El Hierro set it on its path to energy independence.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JordiBusque-portrait.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/db/b7db5f03-b667-4e56-a9f4-170cabcc4188/01-jordibusque.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JordiBusque-portrait.jpg)