How OK Go Has Revolutionized the Music Video

To pull off one of their most daring videos, they needed a borrowed Russian transport jet, spreadsheets and calculus, and a lot of motion-sickness medicine

You aren’t sure what you’re seeing. They all look so polite. Four guys sitting up straight in their jetliner seats, wearing sweaters or tracksuits, bright colors against the gray-on-gray-on-gray interior, their hands resting lightly on their laptops. Friday-casual business trip? Vegas weekend? Nothing strange about it.

But those opening chords. Bumpbump. And those electro-percussive drumbeats. Bumpbumpbump. And now that first laptop just floats away. Bumpbumpbumpbumpbumpbumpbump! Then Damian somersaults out of his seat sideways into the aisle and Dan and Andy start climbing the walls and Tim flies up to the overhead compartments. Two flight attendants float into the frame and spin quick pirouettes in midair. Now the multicolored balls! Andy rides a suitcase! Cue the piñatas! Send in the spinning disco globes! Splatter the neon paint balloons!

In an age of hyperkinetic visual invention, an era up to its eyeballs in images both inventive and clichéd, how do you make something worth watching?

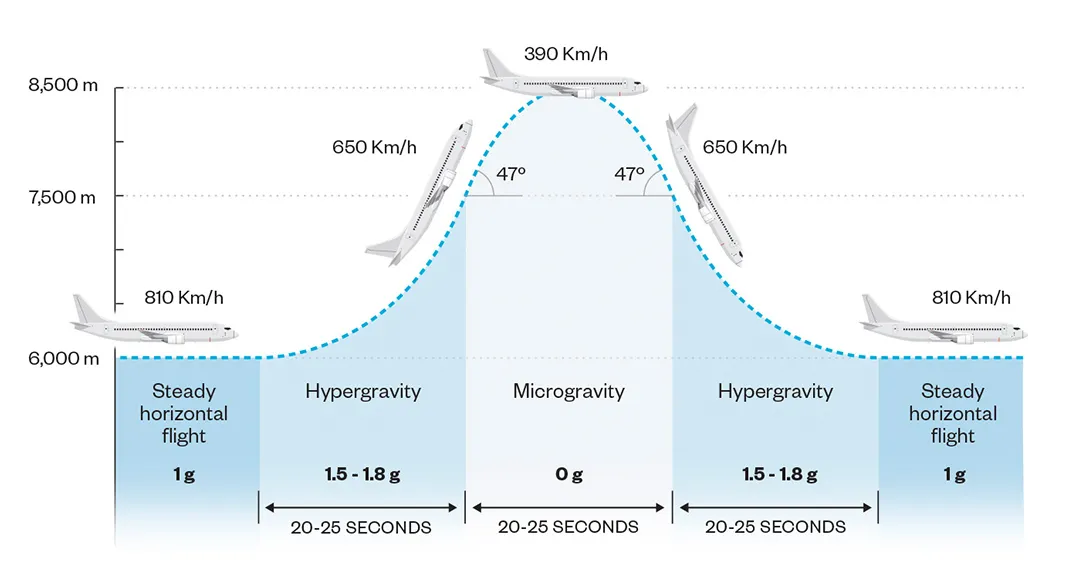

You make this: the video for "Upside Down & Inside Out." Damian Kulash Jr., the band’s guitarist and lead singer, co-directed it with his sister, the choreographer and film director Trish Sie. Shot entirely in zero gravity aboard a converted Russian transport jet flying parabolas—a wave-like series of steep dives and ascents, at the top of which half a minute of weightlessness ensues—the video is a revolution. After a hundred years of clumsy wire work and green-screen make-believe and computer-generated effects, this is the thing itself: (nearly) everything you’d want to do if you were weightless, precisely timed to a song whose signature line is, “Gravity’s just a habit that you’re pretty sure you can’t break.”

Part of this video’s genius is its sinuous continuity, its long “How’d they do that?” single take, and the slow build to the paint-balloons climax. “We wanted this video to be a complete choreography, rather than a montage of awesome things that can be done in zero-G. That was the first big hurdle,” Trish said. To which Damian added, “Because what we didn’t want to do was a bunch of cool stuff and edit it together later. It’s very much not our style—like, where’s the challenge?”

That very question has propelled the band from its beginning 18 years ago. They started in Chicago out of college, succeeded on the club scene, then broke big as regulars on the live tour of the radio program “This American Life.” They moved to Los Angeles, and though often described as “alternative” rock, their music defies easy categorization. It’s smart, mature, self-aware American rock ’n’ roll, with a devoted fan base. And Damian, Andy Ross, Tim Nordwind and Dan Konopka are as famous for their videos as they are for their music. (Damian has directed 15, four with Trish, including “Here It Goes Again” from 2006, which featured a deadpan treadmill ballet, won a Grammy and has been viewed more than 33 million times on YouTube.)

The band will release its latest video, "The One Moment," directed by Damian, across several platforms, including CBS, on November 23.

OK Go’s video for the The One Moment comes out in 6 days. pic.twitter.com/Q7IRocTOnF

— OK Go (@okgo) November 17, 2016

Every song, every image, every gesture is collaborative. As you’d expect of siblings, Trish and Damian, both tall and fair, finish each other’s sentences. Tim and Damian, opposites in affect and appearance, are responsible for the band’s artistic sensibility. The two met at the Interlochen arts camp when they were 11 years old. The band’s name comes from their favorite teacher there, who’d lay out the day’s instructions and say, “OK, go!”

“Upside Down & Inside Out” was initially more of a physics challenge, with spreadsheets and calculus. Damian had heard about parabolic flight a decade ago. “But it’s really super-expensive,” he tells Smithsonian. “So it’s an idea we had for a very long time, but we just basically figured we couldn’t do it. Until the representatives of this Russian airline [S7] came to us and were, like, ‘We want to do something with an airplane.’ And we were, like — ”

“You don’t saaaaaay,” adds Trish, laughing.

Then came the math. The song is 3 minutes and 20 seconds long, give or take. Weightlessness during parabolic flight occurs in roughly 25-second increments. That’s at the top of each parabola. And for every parabola, it takes five minutes of flight to reset for the next one. To get a single continuous weightless take lasting 3:20 would require eight parabolas—more than 45 minutes of actual flying time.

It required three weeks of flying parabolas outside Moscow to get to that take. Every day in and out of the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center at Star City in a big Russian IL-76 MDK. Experimenting with what worked and what didn’t, developing what did work into a series of events, upping the ante with every piñata and disco globe. Then rehearsing it. Then linking one gag to the next to the next. Choreographing the moves. And 315 parabolas. For every second of weightlessness, two with gravity doubled on the way up and the way down. Pinned to your seat, then floating, then pinned to the floor. Think of the motion sickness, even with an assortment of meds. All for one continuous master shot, with the intervals between zero-gravity segments compressed but not cut. It looks seamless because it is.

Director Ron Howard and the cast and crew of 1995’s Apollo 13 had done something similar, but for much shorter scenes. They shot them inside NASA’s KC-135 astronaut trainer. Damian recalls a dinner-party conversation with Tom Hanks, who played Apollo 13 commander Jim Lovell: “The memory I came away with was that they’d done more parabolas in a row, but fewer flights. Tom recalled that they’d gotten ‘a little overconfident’ after a few pukeless but medicated flights, and he decided to brave it without the meds one day. Apparently that was a big mistake.”

Upside down and inside out and 51 million page views later, the calculus and the spreadsheets and the months of conception and prep and nausea drift away, and what’s left is the music and the bounce and the colors and the kind of ingenuity by which a music video becomes a little machine for producing joy.

Hungry Ghosts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/e6/3ee6816f-535c-4dd0-9015-96896a0c95d4/dec2016_d10_ingenuity.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)